IT WAS ONE of those things that you just read and go: ‘This is so. Fucking. Amazing,’” says British actor Stephen Moyer, about the script for True Blood. He’s sitting in a makeup trailer in the parking lot of a strip mall in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, as his tanned face is painted liberally with pale foundation by Brigette Myre Ellis, who not incidentally, was the head of makeup for seven years on television’s last great vampire show, Buffy the Vampire Slayer. (“She knows her vampire shit,” Moyer says, grinning.) The actor, who plays 173-year-old vampire Bill Compton, is in Louisiana along with a significant proportion of the rest of True Blood’s cast and crew for five days to shoot some location scenes (the rest of the time, it shoots in Los Angeles); today he has been filming one of the final scenes of season 2 in a bed-and-breakfast across the street. Outside, evening is falling, and with every passing minute, the whir of the cicadas gets louder. Even though it’s almost 6 p.m., the temperature is still about 100 degrees; the humidity is so stifling it’s like being wrapped in warm, wet weeds.

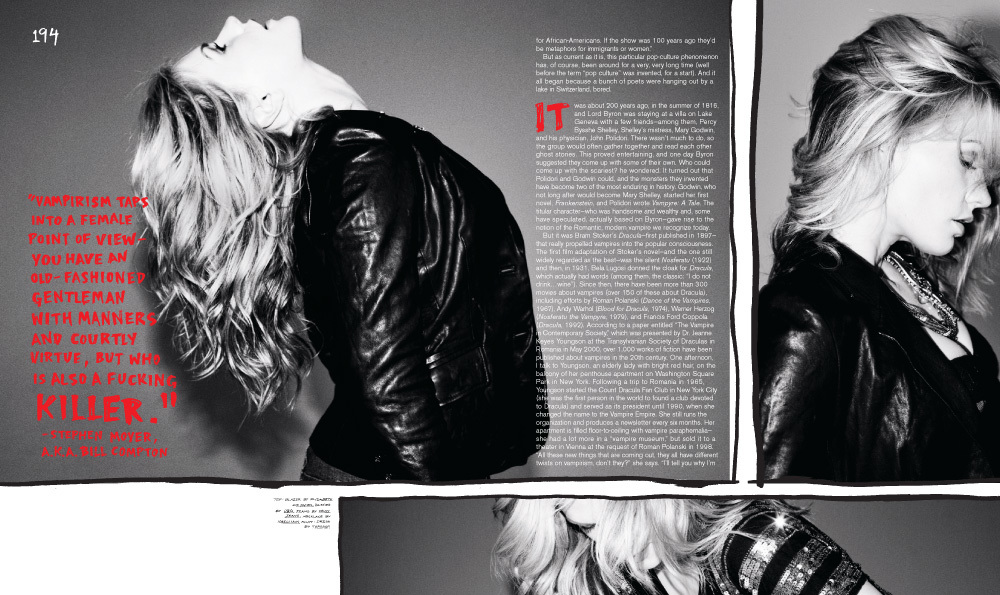

“The thing about vampirism is that it taps into a female point of view—you have an old-fashioned gentleman with manners and courtly virtue, but who is a fucking killer,” Moyer continues, as a bead of sweat runs down his face, leaving a milky trail through the makeup. “It’s an interesting duality, because in our present society it would be an odd thing for a woman to say, ‘I want my man to be physical with me.’ How, as a modern man, can you fucking work that? It’s one thing to be polite and gentle and caring and open the door. But when do you know it’s OK to crawl out of the mud and rape her [as Bill does in one scene]? It’s difficult stuff for a bloke, but a vampire gets away with it because he doesn’t think about it. I think that’s the attraction of the show—it’s looking back at a romantic time when men were men, but they were still charming. It’s funny, it’s dark, it’s twisted, it’s sexy. Alan [Ball, the creator and executive producer] has been very clever. He’s created something for everybody.”

Later, sitting by the craft table during a break, Anna Paquin—who plays our heroine Sookie Stackhouse—concurs. “I think the show does something amazing,” she says, as Moyer comes over and puts a little piece of watermelon in her mouth. “I think you’ll find it good,” he whispers in her ear, then smiles and walks away. (Moyer and Paquin are engaged to be married, and share a house in L.A.) After chewing, swallowing, and wiping away some juice that’s dribbling down her chin, Paquin continues, unabashed: “It walks the line between being serious and funny. It’s been done really beautifully, and it just keeps getting richer.” She looks over to where Moyer is standing and flashes him a quick smile.

THE STORY OF True Blood began about five years ago, when Alan Ball, who at the time was working on the fifth and final season of Six Feet Under, was early for a dentist’s appointment in the San Fernando Valley, California. While killing time in a Barnes & Noble, he noticed a small, unassuming book with the tagline “Maybe having a vampire for a boyfriend wasn’t such a good idea,” on the cover.

“At that point, I had spent five years peering into the existential abyss,” Ball says now. “I was done with that continual meditation upon mortality.” Curious, he bought the book and started reading. “It was so much fun, I could not put it down,” he continues. “At that point, there were three more books in the series and I went through them like candy. I loved the authentic Southernness of them. I loved the social commentary. I loved the romance. I loved the sex. I loved the horror. I loved the suspense. I loved how funny they were.” After a while, he began imagining how he might develop the books into a TV show. “I’m all for entertainment, but I need something underneath it,” says Ball. “And in the books, there was a really tender love story between two people who had basically given up on ever finding anybody. I saw it in my head. I thought, This is a show I would watch.”

The book was Dead Until Dark, the first in a series of novels by Charlaine Harris based on the adventures of a telepathic waitress, Sookie Stackhouse, who falls in love with a vampire, Bill Compton, in a fictional town in Louisiana called Bon Temps. (The series is now nine books strong, and Harris has recently signed a contract with Penguin to write three more: Sookie, much like those whose company she prefers to keep, is not going anywhere for a while.) True Blood, the show that Ball developed from the books, is currently HBO’s most successful (the premiere of season 2 drew more viewers than any other HBO show since the finale of The Sopranos), and Harris’s books are now regular features on The New York Times bestseller list (to date, they have sold more than 10 million copies). When I talk to Harris, who lives in Alabama and says things like “Geez Louise” without irony, she seems hardly to believe her luck. “Before the show, if I had 80 people at a signing, that was super,” she says. “But in Chicago last weekend, I had 700! Talk about being stunned!”

There’s no doubt about it: Vampires are having a moment. At this point, they have infiltrated every last bastion of popular culture—from books (a new Dracula novel, co-authored by none other than Bram Stoker’s great grandnephew—his name, wonderfully, is Dacre Stoker—will come out in October), to movies (The Twilight Saga: New Moon opens on November 20), to television (this month, The Vampire Diaries, another show about the young, good-looking undead premieres on The CW). They are everywhere we turn: on billboards, on the sides of buses, on the covers of magazines. No one is quite sure why, but some people are willing to take a guess.

“When I’m asked about that, I jokingly say it’s because we just got out of an eight-year vampire administration, where evil creatures sucked the blood out of America,” says Ball. “For whatever reason, vampires are a really powerful symbol in people’s subconscious. One thing I have discovered is that a lot of people fantasize about being taken by a vampire, sexually. There is some sort of allure to the idea of this otherwordly, death-defying sexual experience that is so transcendent and ecstatic and orgasmic that both men and women can fantasize about it.”

“In America, we’re all obsessed with youth and staying in peak condition,” says Harris. “Vampires don’t have to go to the gym. They don’t have to die. They don’t have to go on NutriSystem. They don’t have to have new knees. They don’t get high blood pressure—they don’t have any blood pressure! It’s all effortless for them, and I think we’re all going, ‘Gosh, that sure looks good.’”

As with Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula, which came out in 1992 and contained thinly veiled references to AIDS—one of the most preoccupying issues of the time—there is much about these current representations of vampires that reflects today’s social issues. Harris knows this. The vampires in her stories are able to drink bottled, synthetic blood (in a predictable brand extension, you can now buy a soda called Tru Blood, which looks like the drink in the show. The flavor? Blood orange, naturally) and are therefore able to coexist with humans. Harris refers to it as “coming out of the coffin.” Ball knows it, too, and the metaphors in True Blood are right there on the surface. “It’s easy to say that the vampires are a metaphor for the LGBT community, because that’s what’s going on right now,” he says. “If the show was 50 years ago, they’d be metaphors for African-Americans. If the show was 100 years ago they’d be metaphors for immigrants or women.”

But as current as it is, this particular pop-culture phenomenon has, of course, been around for a very, very long time (well before the term “pop culture” was invented, for a start). And it all began because a bunch of poets were hanging out by a lake in Switzerland, bored.

IT WAS ABOUT 200 years ago, in the summer of 1816, and Lord Byron was staying at a villa on Lake Geneva with a few friends—among them, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Shelley’s mistress, Mary Godwin, and his physician, John Polidori. There wasn’t much to do, so the group would often gather together and read each other ghost stories. This proved entertaining, and one day Byron suggested they come up with some of their own. Who could come up with the scariest? he wondered. It turned out that Polidori and Godwin could, and the monsters they invented have become two of the most enduring in history. Godwin, who not long after would become Mary Shelley, started her first novel, Frankenstein, and Polidori wrote Vampyre: A Tale. The titular character—who was handsome and wealthy and, some have speculated, actually based on Byron—gave rise to the notion of the Romantic, modern vampire we recognize today.

But it was Bram Stoker’s Dracula—first published in 1897— that really propelled vampires into the popular consciousness. The first film adaptation of Stoker’s novel—and the one still widely regarded as the best—was the silent Nosferatu (1922) and then, in 1931, Bela Lugosi donned the cloak for Dracula, which actually had words (among them, the classic: “I do not drink...wine”). Since then, there have been more than 300 movies about vampires (over 150 of these about Dracula), including efforts by Roman Polanski (Dance of the Vampires, 1967), Andy Warhol (Blood for Dracula, 1974), Werner Herzog (Nosferatu the Vampyre, 1979), and Francis Ford Coppola (Dracula, 1992). According to a paper entitled “The Vampire in Contemporary Society,” which was presented by Dr. Jeanne Keyes Youngson at the Transylvanian Society of Draculas in Romania in May 2000, over 1,000 works of fiction have been published about vampires in the 20th century. One afternoon, I talk to Youngson, an elderly lady with bright red hair, on the balcony of her penthouse apartment on Washington Square Park in New York. Following a trip to Romania in 1965, Youngson started the Count Dracula Fan Club in New York City (she was the first person in the world to found a club devoted to Dracula) and served as its president until 1990, when she changed the name to the Vampire Empire. She still runs the organization and produces a newsletter every six months. Her apartment is filled floor-to-ceiling with vampire paraphernalia— she had a lot more in a “vampire museum,” but sold it to a theater in Vienna at the request of Roman Polanski in 1998. “All these new things that are coming out, they all have different twists on vampirism, don’t they?” she says. “I’ll tell you why I’m still in business: The vampires of Bram Stoker and all his friends have a lot of spider webs that go out and touch everything.... From Oscar Wilde to Walt Whitman to Henry Irving and movies...everything.”

Aside from Stoker’s classic, the most significant works of vampire fiction are Anne Rice’s “Vampire Chronicles” (which started in 1976 with Interview With the Vampire), and Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot (which was made into a TV miniseries in 1979). After this, things on the vampire-fiction front went relatively quiet (at least in the mainstream: “paranormal fiction,” much of it erotic, continued to flourish) for a while. Then, along came Stephenie Meyer’s “Twilight” series and Charlaine Harris’s Sookie Stackhouse stories (there were others too, among them the “Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter” books, a series of erotic novels by Laurell K. Hamilton) and, with them, a new fanbase so wide, and so fervent, that the genre might never be the same again.

“When writers are able to come up with something new or something different and tell the same old story with a vampire twist, then vampires come to the fore again,” says Dr. Elizabeth Miller, who is based in Toronto and is one of the world’s leading scholars of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. “Vampires are versatile; you can mold them any way you want to. Vampires now appeal to a whole new class of reader that had no interest whatsoever in vampires before.” Indeed, crucial to the success of both Harris and Meyer is the way in which they have re-imagined the vampire by discarding some stereotypes, accentuating others, and coming up with some new ones all their own.

These new vampires are a different breed. Before, they had manly, respectable names like “Vlad the Impaler” and “Nosferatu.” Now, our heroes are called “Edward” and “Bill.” Vampires of the past would rip the bodices off the women they seduced, then drain their blood. Today, they walk them home from school, cuddle them, and then make them a mixtape. When they were hungry, they’d slash someone’s artery and slurp away until they were full, not put a bottle of fake blood in the microwave for two minutes. If they wanted to get somewhere, they’d turn into a bat and fly—they most certainly would not drive there in an Audi. Early vampires were often hideous, but these modern incarnations are impossibly handsome. “His lips were lovely, sharply sculpted, and he had arched dark brows. His nose swooped down right out of that arch, like a prince’s in a Byzantine mosaic,” is how Sookie describes Bill in Dead Until Dark. In Twilight, Meyer’s heroine, Bella, describes the faces of the vampires as “all devastatingly, inhumanly beautiful. They were faces you never expectedto see, except perhaps on the airbrushed pages of a fashion magazine.” But while both the “Twilight” and Sookie Stackhouse series’ concern themselves with a distinctly secular form of vampirism, there are key differences between them. In Meyers’s books, which target a younger reader, the violence is often abstract and sex is something withheld by the hero, Edward. Sookie holds out on Bill for a while, too, but once they start, they don’t stop. The sex in Harris’s novels, and in True Blood, is frequent and graphic—the violence gory, and often horrific.

“True Blood is a grown-up show,” says Melissa Lowery, who, with Elizabeth Henderson, runs one of the most popular True Blood fansites, True-blood.net. “Twilight is True Blood-lite. I don’t recommend True Blood for anyone under 21.”

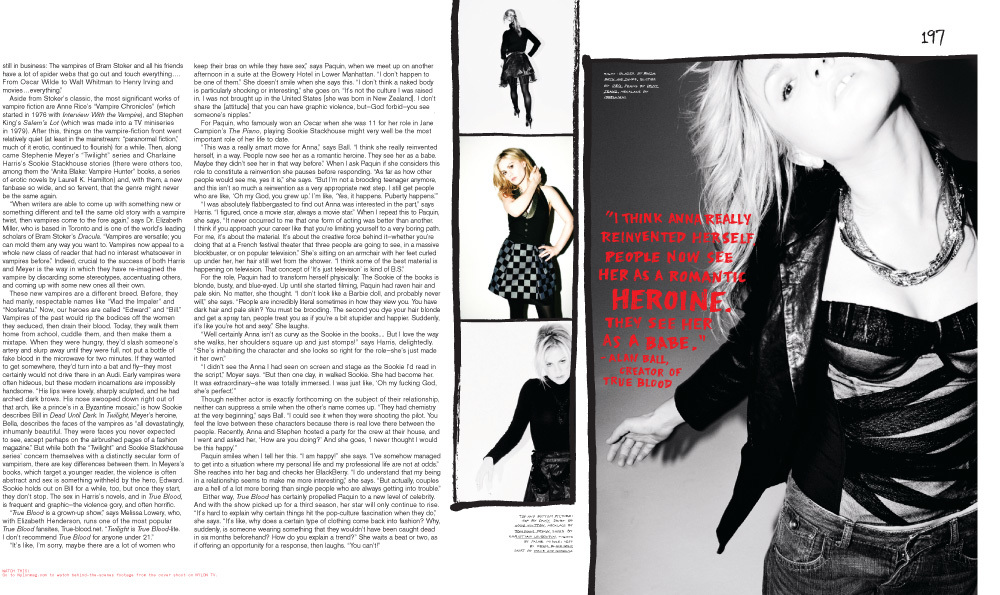

“It’s like, I’m sorry, maybe there are a lot of women who keep their bras on while they have sex,” says Paquin, when we meet up on another afternoon in a suite at the Bowery Hotel in Lower Manhattan. “I don’t happen to be one of them.” She doesn’t smile when she says this. “I don’t think a naked body is particularly shocking or interesting,” she goes on. “It’s not the culture I was raised in. I was not brought up in the United States [she was born in New Zealand]. I don’t share the [attitude] that you can have graphic violence, but—God forbid—you see someone’s nipples.”

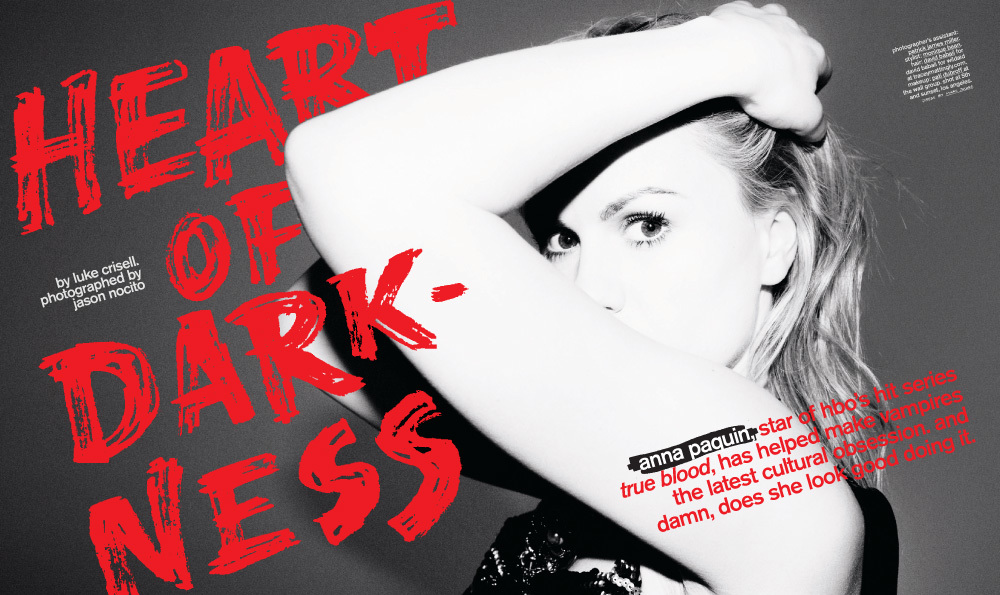

For Paquin, who famously won an Oscar when she was 11 for her role in Jane Campion’s The Piano, playing Sookie Stackhouse might very well be the most important role of her life to date.

“This was a really smart move for Anna,” says Ball. “I think she really reinvented herself, in a way. People now see her as a romantic heroine. They see her as a babe. Maybe they didn’t see her in that way before.” When I ask Paquin if she considers this role to constitute a reinvention she pauses before responding. “As far as how other people would see me, yes it is,” she says. “But I’m not a brooding teenager anymore, and this isn’t so much a reinvention as a very appropriate next step. I still get people who are like, ‘Oh my God, you grew up.’ I’m like, ‘Yes, it happens. Puberty happens.’”

“I was absolutely flabbergasted to find out Anna was interested in the part,” says Harris. “I figured, once a movie star, always a movie star.” When I repeat this to Paquin, she says, “It never occurred to me that one form of acting was better than another. I think if you approach your career like that you’re limiting yourself to a very boring path. For me, it’s about the material. It’s about the creative force behind it—whether you’re doing that at a French festival theater that three people are going to see, in a massive blockbuster, or on popular television.” She’s sitting on an armchair with her feet curled up under her, her hair still wet from the shower. “I think some of the best material is happening on television. That concept of ‘It’s just television’ is kind of B.S.”

For the role, Paquin had to transform herself physically: The Sookie of the books is blonde, busty, and blue-eyed. Up until she started filming, Paquin had raven hair and pale skin. No matter, she thought. “I don’t look like a Barbie doll, and probably never will,” she says. “People are incredibly literal sometimes in how they view you. You have dark hair and pale skin? You must be brooding. The second you dye your hair blonde and get a spray tan, people treat you as if you’re a bit stupider and happier. Suddenly, it’s like you’re hot and sexy.” She laughs.

“Well certainly Anna isn’t as curvy as the Sookie in the books.... But I love the way she walks, her shoulders square up and just stomps!” says Harris, delightedly. “She’s inhabiting the character and she looks so right for the role—she’s just made it her own.”

“I didn’t see the Anna I had seen on screen and stage as the Sookie I’d read in the script,” Moyer says. “But then one day, in walked Sookie. She had become her. It was extraordinary—she was totally immersed. I was just like, ‘Oh my fucking God, she’s perfect.’”

Though neither actor is exactly forthcoming on the subject of their relationship, neither can suppress a smile when the other’s name comes up. “They had chemistry at the very beginning,” says Ball. “I could see it when they were shooting the pilot. You feel the love between these characters because there is real love there between the people. Recently, Anna and Stephen hosted a party for the crew at their house, and I went and asked her, ‘How are you doing?’ And she goes, ‘I never thought I would be this happy.’”

Paquin smiles when I tell her this. “I am happy!” she says. “I’ve somehow managed to get into a situation where my personal life and my professional life are not at odds.” She reaches into her bag and checks her BlackBerry. “I do understand that my being in a relationship seems to make me more interesting,” she says. “But actually, couples are a hell of a lot more boring than single people who are always getting into trouble.”

Either way, True Blood has certainly propelled Paquin to a new level of celebrity. And with the show picked up for a third season, her star will only continue to rise. “It’s hard to explain why certain things hit the pop-culture fascination when they do,” she says. “It’s like, why does a certain type of clothing come back into fashion? Why, suddenly, is someone wearing something that they wouldn’t have been caught dead in six months beforehand? How do you explain a trend?” She waits a beat or two, as if offering an opportunity for a response, then laughs. “You can’t!”