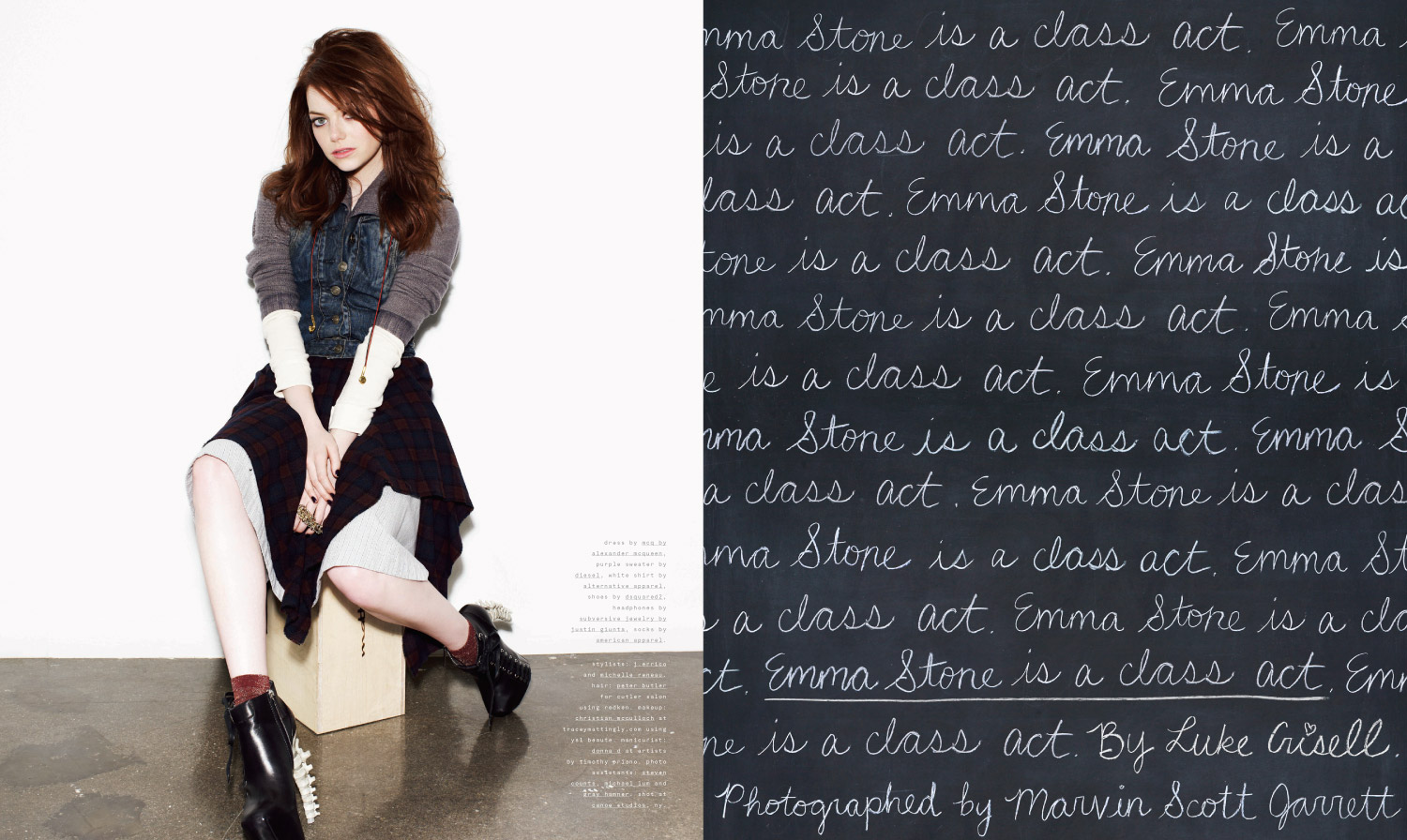

EMMA STONE IS A CLASS ACT

It’s just before dusk, and the last of the day’s sunlight is flooding through the wide streets of Greenwood, Mississippi, making everything glow like burnished copper. The mansions—modest, but mansions nonetheless—that line Grand Boulevard are quiet, the occasional slap of a screen door the only indication that anyone might be living in them at all. This street was once named one of the 10 most beautiful in America and the 1,000 oak trees along it, planted almost a century ago, stand tiredly in the terrific August heat which even now, as the sun is going down, is as sweet and sticky as syrup; so thick it seems not to have a scent so much as a taste. The cars come infrequently and move slowly: When they pass, Emma Stone and I have to ride our bikes single file— we pull alongside each other again once they’ve gone on their way. Aside from the persistent, mechanical hum of cicadas, everything seems muted; a soporific stillness has settled over the town like a veil.

Stone is in Greenwood to film The Help, a drama set in ’60s Mississippi which will be released next year, and for the past two months she’s been living in a stately white manor with imposing Doric columns and double-height ceilings—a world away from the two bedroom apartment in New York City’s East Village that she normally calls home. A bike ride seemed like a good idea when we were drinking ice-cold cocktails in an air conditioned hotel bar a few hours ago, but now we’re both succumbing to the effects of the heat, dripping in sweat as we cross a bridge over a subsidiaryof the Tallahatchie River and leave the town’s limits, heading through fields of sugarcane toward a house where, the previous day, Stone was filming a scene for The Help. Built in 1902, the building is a typical Mississippi Delta plantation structure—white, pillared, with wraparound porches and gardens that stretch out on every side. Camera equipment and generators sit on the lawn out front, ready to be started up again when filming resumes on Monday, two days from now.

“Shall I knock?” asks Stone, looking up at the windows for some sign of life. She goes up to the front door then decides against the idea and gestures to a swinging chair at one end of the patio. “Bryce [Dallas Howard] and I were filming a scene there yesterday,” she says, red in the face. “Can you imagine trying to act in this heat? It’s insane!” She turns and looks across the fields, which stretch as far as we can see in every direction; a sea of dusty browns. The sun has all but gone, and flashes of orange flicker in the sky like embers. “It’s so beautiful though. I mean, how lucky are we that our jobs bring us to places like this?” We get back on our bikes. “Right, let’s go get something to eat,” she says.“I’m starving, and this wine”—she has brought a bottle of Cabernet Sauvignon in her basket—“isn’t going to drink itself.”

Riding back into town from the plantation house, we pass a bar with a banner outside reading Webster’s Welcomes the Cast and Crew of The Help, and Stone points out the street that leads to the local Sonic Drive-In. “We have to go there later!” she says. “Sonic is my favorite.” It’s 8 p.m. on a Saturday, but the streets are deserted as we turn into the main square and stop opposite the town hall, where Stone is going to be filming in a few weeks. As we’re about to continue on to the restaurant, an ivory- colored Ford SUV pulls up next to us, stopping in the middle of the street. It would be blocking traffic, if there were any traffic to block. “Excuse me,” says a blond woman with a thick Southern accent, “are you Emma Stone?”

“I am,” Stone responds, smiling.

“I told you!” says the woman triumphantly, turning to her family in the car. Two children are staring incredulously from the backseat, through tinted windows. “My children love you! I love you! And I saw you and thought it was you, but I wasn’t sure. How do y’all like Greenwood?’

“It’s great!” says Stone, going over to the car and making small talk with the family for five minutes.

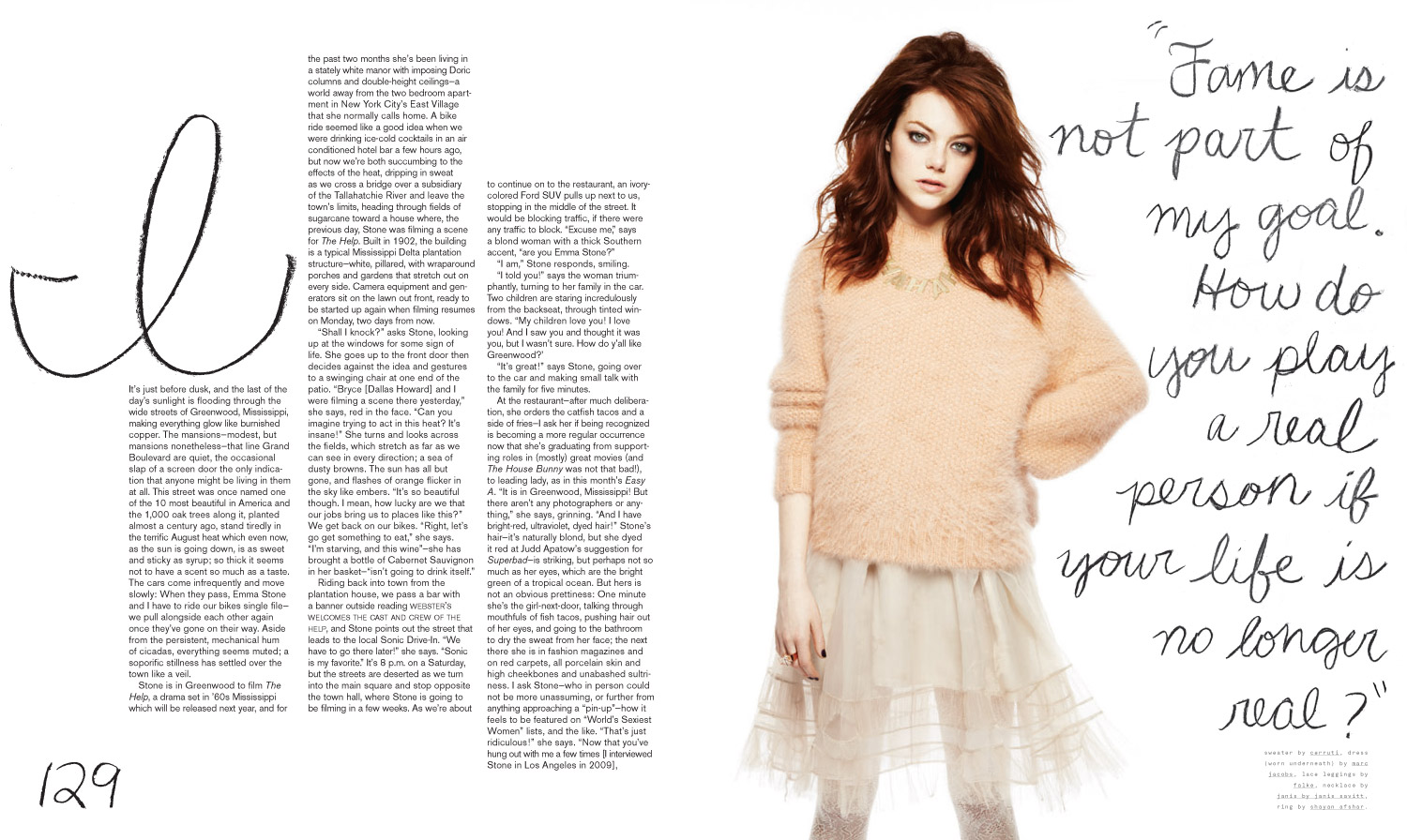

At the restaurant—after much deliberation, she orders the catfish tacos and a side of fries—I ask her if being recognized is becoming a more regular occurrence now that she’s graduating from supporting roles in (mostly) great movies (and The House Bunny was not that bad!), to leading lady, as in this month’s Easy A. “It is in Greenwood, Mississippi! But there aren’t any photographers or anything,” she says, grinning. “And I have bright-red, ultraviolet, dyed hair!” Stone’s hair—it’s naturally blond, but she dyed it red at Judd Apatow’s suggestion for Superbad—is striking, but perhaps not so much as her eyes, which are the bright green of a tropical ocean. But hers is not an obvious prettiness: One minute she’s the girl-next-door, talking through mouthfuls of fish tacos, pushing hair out of her eyes, and going to the bathroomto dry the sweat from her face; the next there she is in fashion magazines and on red carpets, all porcelain skin and high cheekbones and unabashed sultriness. I ask Stone—who in person could not be more unassuming, or further from anything approaching a “pin-up”—how it feels to be featured on “World’s Sexiest Women” lists, and the like. “That’s just ridiculous!” she says. “Now that you’ve hung out with me a few times [I interviewed Stone in Los Angeles in 2009], you know how ridiculous that is. All my friends and family are like, ‘That is the funniest thing I have ever seen.’” Throughout her career, directors have utilized Stone’s ability to go from cute to sexy with barely a swipe of eye makeup and a pair of heels, and Will Gluck, director of Easy A, is no exception.

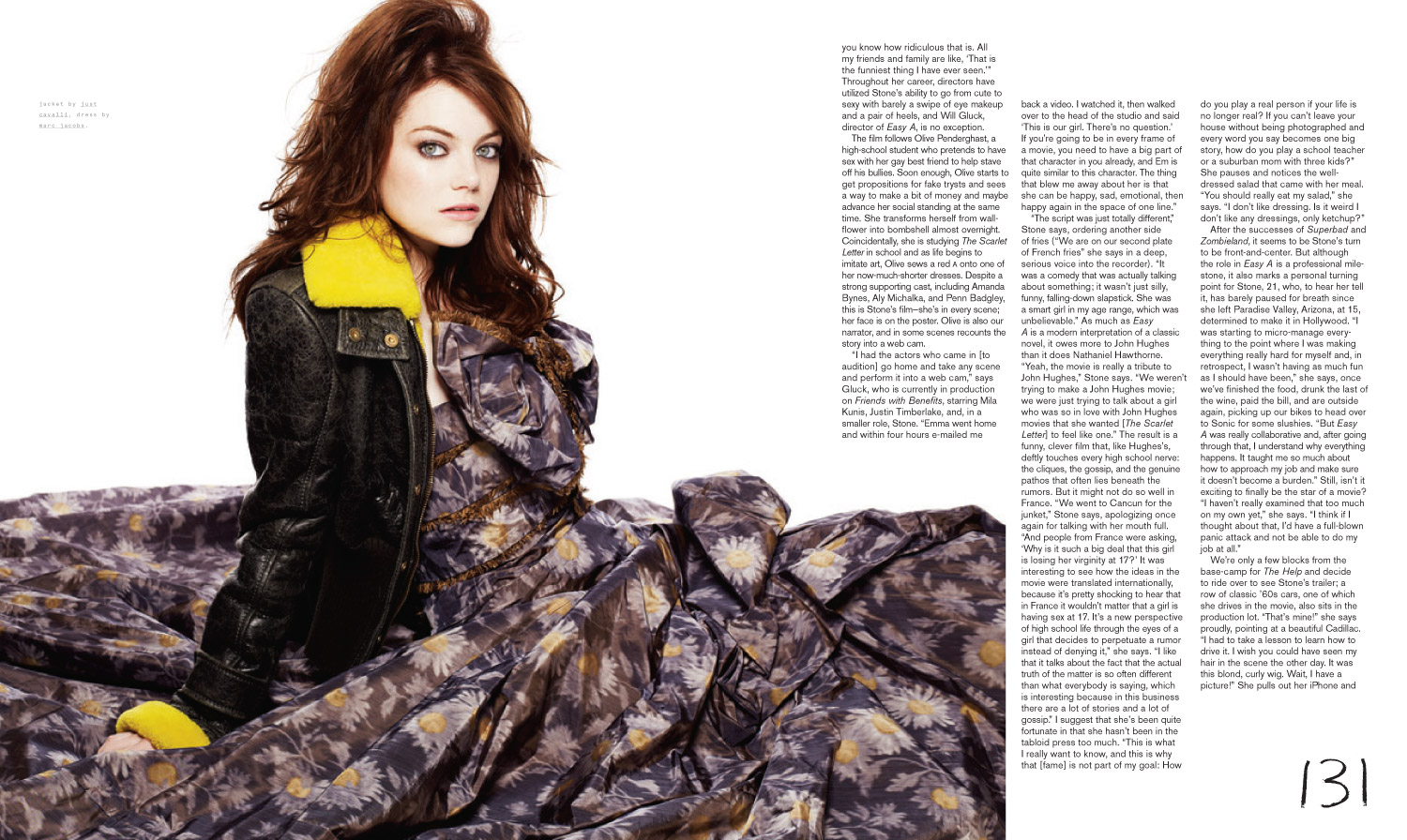

The film follows Olive Penderghast, a high-school student who pretends to have sex with her gay best friend to help stave off his bullies. Soon enough, Olive starts to get propositions for fake trysts and sees a way to make a bit of money and maybe advance her social standing at the same time. She transforms herself from wallflower into bombshell almost overnight. Coincidentally, she is studying The Scarlet Letter in school and as life begins to imitate art, Olive sews a red a onto one of her now-much-shorter dresses. Despite a strong supporting cast, including Amanda Bynes, Aly Michalka, and Penn Badgley, this is Stone’s film—she’s in every scene; her face is on the poster. Olive is also our narrator, and in some scenes recounts the story into a webcam.

“I had the actors who came in [to audition] go home and take any scene and perform it into a webcam,” says Gluck, who is currently in production on Friends with Benefits, starring Mila Kunis, Justin Timberlake, and, in a smaller role, Stone. “Emma went home and within four hours e-mailed me back a video. I watched it, then walked over to the head of the studio and said ‘This is our girl. There’s no question.’ If you’re going to be in every frame of a movie, you need to have a big part of that character in you already, and Em is quite similar to this character. The thing that blew me away about her is that she can be happy, sad, emotional, then happy again in the space of one line.”

“The script was just totally different,” Stone says, ordering another side of fries (“We are on our second plate of French fries” she says in a deep, serious voice into the recorder). “It was a comedy that was actually talking about something; it wasn’t just silly, funny, falling-down slapstick. She was a smart girl in my age range, which was unbelievable.”

As much as Easy A is a modern interpretation of a classic novel, it owes more to John Hughes than it does Nathaniel Hawthorne. “Yeah, the movie is really a tribute to John Hughes,” Stone says. “We weren’t trying to make a John Hughes movie; we were just trying to talk about a girl who was so in love with John Hughes movies that she wanted [The Scarlet Letter] to feel like one.” The result is a funny, clever film that, like Hughes’s, deftly touches every high school nerve: the cliques, the gossip, and the genuine pathos that often lies beneath the rumors. But it might not do so well in France. “We went to Cancun for the junket,” Stone says, apologizing once again for talking with her mouth full. “And people from France were asking, ‘Why is it such a big deal that this girl is losing her virginity at 17?’ It was interesting to see how the ideas in the movie were translated internationally, because it’s pretty shocking to hear that in France it wouldn’t matter that a girl is having sex at 17. It’s a new perspective of high school life through the eyes of a girl that decides to perpetuate a rumor instead of denying it,” she says. “I like that it talks about the fact that the actual truth of the matter is so often different than what everybody is saying, which is interesting because in this business there are a lot of stories and a lot of gossip.” I suggest that she’s been quite fortunate in that she hasn’t been in the tabloid press too much. “This is what I really want to know, and this is why that [fame] is not part of my goal: How do you play a real person if your life is no longer real? If you can’t leave your house without being photographed and every word you say becomes one big story, how do you play a school teacher or a suburban mom with three kids?” She pauses and notices the well- dressed salad that came with her meal. “You should really eat my salad,” she says. “I don’t like dressing. Is it weird I don’t like any dressings, only ketchup?”

After the successes of Superbad and Zombieland, it seems to be Stone’s turn to be front-and-center. But although the role in Easy A is a professional milestone, it also marks a personal turning point for Stone, 21, who, to hear her tell it, has barely paused for breath since she left Paradise Valley, Arizona, at 15, determined to make it in Hollywood. “I was starting to micro-manage everything to the point where I was making everything really hard for myself and, in retrospect, I wasn’t having as much fun as I should have been,” she says, once we’ve finished the food, drunk the last of the wine, paid the bill, and are outside again, picking up our bikes to head over to Sonic for some slushies. “But Easy A was really collaborative and, after going through that, I understand why everything happens. It taught me so much about how to approach my job and make sure it doesn’t become a burden.” Still, isn’t it exciting to finally be the star of a movie? “I haven’t really examined that too much on my own yet,” she says. “I think if I thought about that, I’d have a full-blown panic attack and not be able to do my job at all.”

We’re only a few blocks from the base-camp for The Help and decide to ride over to see Stone’s trailer; a row of classic ’60s cars, one of which she drives in the movie, also sits in the production lot. “That’s mine!” she says proudly, pointing at a beautiful Cadillac. “I had to take a lesson to learn how to drive it. I wish you could have seen my hair in the scene the other day. It was this blond, curly wig. Wait, I have a picture!” She pulls out her iPhone and shows me a photo of herself in period costume, wearing what is indeed a fan- tastic wig. The picture is covered in cats. “Have you seen the CatPaint app?” she asks, excitedly. “It will change your life. Look at all the cats I’ve added!”

The next day, Stone and I drive the two hours across the Delta to Oxford, Mississippi, the home of Ole Miss and, for a while, William Faulkner. There are no coffee shops in Greenwood, and so we head straight to one as soon as we get to Oxford, which is almost as somnolent as Greenwood, but a lot prettier. The temperature display in Stone’s yellow Beetle reads 96 degrees, and it’s only going to get hotter. I tell her that today we should start at the beginning. “Oh, how very Sound of Music of you,” she says, with a winning smile. “Go on then.”

Stone was born in Scottsdale, Arizona, in 1988. Her real name is Emily. She changed it to Emma because Emily Stone was already taken at the Screen Actors Guild, but she still goes by Emily legally and among old friends, and she signs her name E. Stone. Her father is Swedish (his last name was originally Sten—he changed it to Stone at Ellis Island), and her mother is from Delaware. Her father started a general contracting firm in 1986, which grew from a local business to a very successful company that now builds hotels and offices all over Arizona, Southern California, and Las Vegas. When Stone was in kindergarten, her teacher put her in a school play (there was only one part for a kindergartner, all the others were for fifth graders) called No Turkey for Perky. “And I just loved it!” she says. “Because I was so goddamn loud.” When she was 11, Stone joined an improv troop at a youth theater in her town. “I still love improv the most,” she says. “To this day. And sketch comedy.” I ask Stone if she was drawn more to the acting part or to the getting-attention part of being on stage. “Probably both,” she replies. “I always wanted to do comedy, and anybody that wants to do comedy has to have some need to please people or need to make people laugh.” I mention that The Help—which is based on the bestselling novel by Kathryn Stockett and tells the story of Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan, a 22-year-old who returns home after graduating from Ole Miss in 1962 during the nascent civil rights movement newly re-attuned to the dubious politics of her small town—does not seem very funny at all. “No it’s not!” Stone says, delightedly. “Which is wild!” I ask if it was a difficult decision to take on the role, considering that she’s known for comedic roles. “I don’t really care what I’m known for,” says Stone. “That’s the thing I’ve had to give up. That part isn’t anything I’ve really thought about.”

When she convinced her parents to let her leave school and head to Los Angeles, it was “under the guise of it just being for pilot season,” Stone says. “I was like, ‘I have this need to move to L.A. I have this feeling that I need to go right now, during my freshman year.’” Belief in their daughter’s conviction (“I had always loved acting, so they knew it wasn’t some fleeting ‘I want to be a veterinarian thing’”) saw Stone’s parents buying up books about acting and,not long after that, Stone moved into a small apartment in L.A. with her mom (the rest of the family stayed behind). “It’s funny because as I get older, I think more about what I would be like as a parent and there’s no way in hell I would ever say yes to that,” Stone says. “I’ve become more appreciative as I get older that they said it was OK, and they didn’t let me become some crazy, emancipated nutter.” A pause. “That was not me saying emancipated people are insane.”

One day, her mother made her audition for a part Stone had no interest in. “It was an open call, like American Idol. I had a number pinned to my chest. I wasn’t used to it at all. I didn’t want to do it: It was scary and weird and I cried the entire time,” Stone says. “But it was the one time my mom has ever pushed me to do anything. She kept saying, ‘I’m so sorry, but I have this weird gut feeling.’” Stone won the part, of Laurie Partridge in a VH1 reality show called In Search of the Partridge Family, but the resulting show, The New Partridge Family, never got further than the pilot. During the process though, Stone met Doug Wald, who has been her manager ever since. “He’s the professional love of my life,” Stone effuses. “He talks me through everything.” Stone had a few guest spots on TV shows, including Malcolm in the Middle and Drive, but despite her relative lack of work, says she never gave up hope of that one big break. “Biannually, I would have a breakdown and cry really hard, and my mom would ask, ‘Do you want to go home?’ And I would always say no, immediately. I didn’t want to go home, but I needed to freak out about it for a little bit.”

Then, in 2007, Judd Apatow cast her as the object of Jonah Hill’s affection in Superbad. “It’s weird, because you can never separate yourself from it,” Stone says of the role. We’ve arrived at Square Books, which sits on a corner of the picture-postcard Courthouse Square in the heart of Oxford, and is one of the most esteemed bookstores in the South, if not America. “It was the gauge I got from my brother, who at the time was a high schooler in Phoenix, that was most accurate for me. All of his friends were quoting the movie in the locker room!”

We go upstairs to the fiction section, where Stone picks up a copy of Hemingway’s semi-autobiographical A Moveable Feast. Earlier, I had told her that in a few days I was going to Key West, Florida, where Hemingway lived for 30 years. “This is one of my favorite books,” she says, thumbing through the pages and reading a few passages to herself. “I’m going to buy it for you. I want some book recommendations, too, though!” She ends up leaving with over $100 worth of books, including The God Delusion and Love in the Time of Cholera.

Stone’s next significant role was in Zombieland, in which she starred alongside Jesse Eisenberg and Woody Harrelson. In an e-mail, I ask Harrelson for his opinion on Stone. “Emma is a rare combination of fierce intelligence, stunning beauty, boundless humor, and someone you just wanna hang with,” he writes back. “She reminds me of Lauren Bacall—young and innocent but with the voice of a woman three times her age who has seen it all. Bill Murray, who never throws out compliments, says she is pure gold.” Ah yes, Bill Murray was in Zombieland, too. For a girl obsessed with all things funny, it must have been exciting to act alongside a comedic legend. “I actually got to ask him about Gilda Radner!” Stone says, thrilled. “It was one of the greatest moments ever.” We stop a lady and her daughter on the street to ask for a recommendation for lunch, and start walking down the hill toward the café they suggest. “But that was followed by perhaps the greatest moment ever, which was introducing him to my dad. My dad showed me every comedy as a kid; he’s a die-hard Bill Murray fan. And I was talking to Bill outside his trailer and my dad pulledup in a car, and I asked Bill if he would come meet my dad. My dad just pulled this face like I’ve never seen. Like, after all that, leaving home and doing all I’ve done, to see my dad meet Bill Murray on the set of I movie I got to do? It was a life-defining moment. The best ever. That night we all drank margaritas and played pool—Bill and I were on one team and Woody and my dad were on another.”

Everyone I speak to about Stone can’t say enough good things about her. I ask Taylor Swift, one of her best friends since the two met at the MTV Movie Awards in 2007, what she thinks is the key to Stone’s burgeoning success. “Emma is successful because she lives, sleeps, breathes, loves, and adores acting,” Swift says. “She doesn’t just watch movies, she studies them. She’s constantly trying to stretch what she’s capable of. She’s excellent at being sarcastic, but then she can be vulnerable and hurt...there’s something real and authentic about her acting and the way she carries herself that just makes you believe her. I would trust her with any secret, because not only would she keep it...she’d find some way to make me laugh about it.”

With three movies set to come out next year—including Crazy, Stupid, Love alongside Steve Carell, Julianne Moore, and Ryan Gosling—Stone is finally in a position to take stock of what she’s been doing for the last six years, and after lunch—and a quick stop at Sonic for slushies—as we drive up to Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s house from 1930 to his death in 1962, she seems in contemplative mood. “I have never wanted to do anything but this,” she says. “One day I just had this really strong urge to go and do it, and I’ve never really examined why. I knew it made me happy, that’s all. But I’m examining it now and it’s funny because we’re in an interview. This is not therapy!” She laughs. “But it’s interesting because we do the same kind of thing, which is getting to know people and aspects of their personality. You write about them and break them down and I try to play them. That’s all it really is: trying to make someone come to life.”

We park the car and walk up to the house, a Greek revival building which sits at the end of a short driveway lined with cedars. It’s mid-afternoon and incredibly peaceful. Tufts of moss stick up between the bricks on the path, which are arranged herringbone style. “I think this is the first time that I can step back and figure out who I am; it’s like I’m in college figuring out what I want to do and who I want to be,” she says. I ask Stone if now that she’s “made it,” she still feels that burning ambition she felt when she first started out. “I think as time has gone on, ambition has become a dirty word to me,” she says. “It sounds like you’d do anything. And for so long I was lucky in that I always knew what I wanted to do, and I’m lucky that I still love to do it as my job. I had such a one track mind for so long, and in the beginning the goals seemed pretty lofty. But this was always the goal. This was the dream.

“My goal was never to win an award,” Stone continues. “It was just to call this my job and for this to be the only thing I have to do. I know it won’t last forever, but the fact that, right now, it’s happening...it’s almost like my brain doesn’t know quite what to do. For so long I was learning by doing, and now I kind of want to learn first and then do.”

After looking around the sparse house, we walk back out through the gardens. The heat is oppressive. In front of us, a butterfly has settled on the path; it makes no effort to fly away as we bend down to look it. Its iridescent blue wings open and close slowly. “You know lots of butterflies only live for a day?” Stone says. “It must be dying.

“The only way I can justify doing this as a job is because it’s fulfilling,” she says. “If a job isn’t fulfilling something in your life, then it seems kind of pointless. I would just go and find another job. For the first time in my life, I am working on being more in the present. For so long I was anxious about the future. But it’s been seven years since I left home and now I’m here getting to do this, sitting in Oxford, Mississippi. I’m just trying to enjoy where I am right now and I know that I’m really young and that’s only going to last for a little while.”

It’s almost time to go our separate ways—I have a plane to catch and Stone says she might stay and watch a film in Oxford since there’s no movie theater in Greenwood. “Movies have always really affected me,” she says (later she e-mails me a list of her favorite movies—including City Lights, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, Network, Manhattan, and Harold and Maude—insisting I watch them). “And when it’s been a really long day and I’m trying to amp myself up a little bit, I think about how I get to make things that potentially will make people feel the way movies made me feel. And to be in something like that is genuinely really wild.”

I think my ultimate goal at the end of the day is to make my parents laugh,” she says. We’re back at the car now: Our slushies have melted in their plastic cups. She sighs quietly, through a smile. “Maybe that is what this is all about: a roundabout way of trying to entertain my parents, just like I did in the living room when I was a kid.”