CLEAN AND SERENE

Liechtenstein’s population is under 35,000 people, yet it is the registered home of 70,000 companies and 15 boutique banks. There is just one anachronism in this modern thriving state: a ruling prince who has little time for the niceties of democracy. Oddly, his subjects seem equally bemused by its appeal.

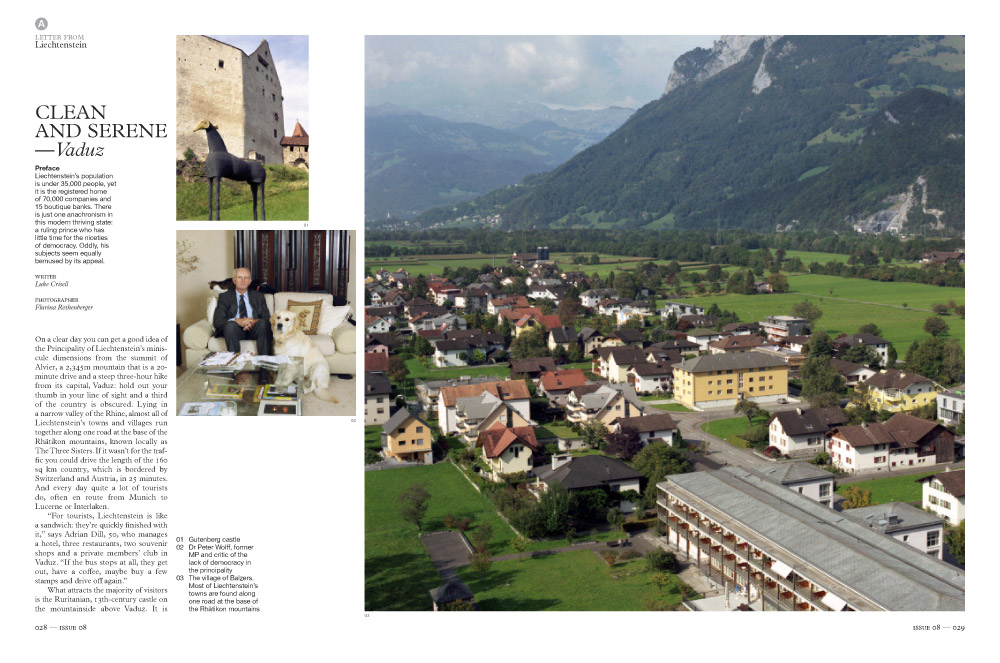

On a clear day you can get a good idea of the Principality of Liechtenstein’s miniscule dimensions from the summit of Alvier, a 2,345m mountain that is a 20-minute drive and a steep three-hour hike from its capital, Vaduz: hold out your thumb in your line of sight and a third of the country is obscured. Lying in a narrow valley of the Rhine, almost all of Liechtenstein’s towns and villages run together along one road at the base of the Rhätikon mountains, known locally as The Three sisters. If it wasn’t for the traffic you could drive the length of the 160 sq km country, which is bordered by Switzerland and Austria, in 25 minutes. And every day quite a lot of tourists do, often en route from Munich to Lucerne or Interlaken.

“For tourists, Liechtenstein is like a sandwich: they’re quickly finished with it,” says Adrian Dill, 50, who manages a hotel, three restaurants, two souvenir shops and a private members’ club in Vaduz. “If the bus stops at all, they get out, have a coffee, maybe buy a few stamps and drive off again.”

What attracts the majority of visitors is the Ruritanian, 13th-century castle on the mountainside above Vaduz. It is currently occupied by His Serene Highness Prince Hans-Adam von und zu Liechtenstein, 62 and his 39-year-old son, His serene Highness Prince Alois (since 2004 deputy head of state).

Although Liechtenstein has been a monarchy since 1719, it wasn’t until 1938 that a reigning Prince of Liechtenstein, Franz Josef, actually lived in the country. Hans-Adam succeeded Franz Josef, his father, in1989. Today, he is the sixth richest head of state with a personal fortune estimated at €3bn, one of the most valuable private art collections in the world, and greater constitutional powers than any other European monarch.

Hans-Adam is a low-key man who drives himself in his black Audi, flies economy class and can often be seen jogging in the woods around the castle. When we visit his home and ask the gatekeeper from the local security firm where the guards are, he replies: “What do you mean? I’m here.”

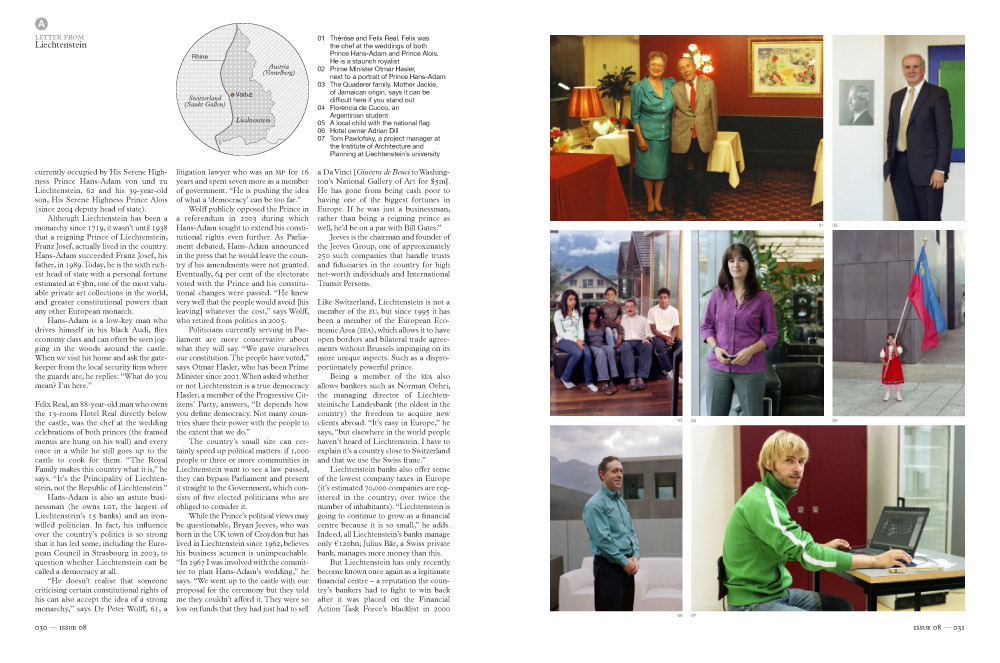

Felix real, an 88-year-old man who owns the 13-room Hotel Real directly below the castle, was the chef at the wedding celebrations of both princes (the framed menus are hung on his wall) and every once in a while he still goes up to the castle to cook for them. “The Royal Family makes this country what it is,” he says. “It’s the Principality of Liechtenstein, not the Republic of Liechtenstein.”

Hans-Adam is also an astute businessman (he owns LGT, the largest of Liechtenstein’s 15 banks) and an iron-willed politician. In fact, his influence over the country’s politics is so strong that it has led some, including the European council in Strasbourg in 2003, to question whether Liechtenstein can be called a democracy at all.

“He doesn’t realise that someone criticising certain constitutional rights of his can also accept the idea of a strong monarchy,” says Dr. Peter Wolff, 61, a litigation lawyer who was an MP for 16 years and spent seven more as a member of government. “He is pushing the idea of what a ‘democracy’ can be too far.”

Wolff publicly opposed the Prince in a referendum in 2003 during which Hans-Adam sought to extend his constitutional rights even further. As Parliament debated, Hans-Adam announced in the press that he would leave the country if his amendments were not granted. Eventually, 64 per cent of the electorate voted with the Prince and his constitu- tional changes were passed. “He knew very well that the people would avoid [his leaving] whatever the cost,” says Wolff, who retired from politics in 2005.

Politicians currently serving in Parliament are more conservative about what they will say. “We gave ourselves our constitution. The people have voted,” says Otmar Hasler, who has been Prime Minister since 2001.When asked whether or not Liechtenstein is a true democracy Hasler, a member of the Progressive Citizens’ Party, answers, “It depends how you define democracy. Not many countries share their power with the people to the extent that we do.”

The country’s small size can certainly speed up political matters: if 1,000 people or three or more communities in Liechtenstein want to see a law passed, they can bypass Parliament and present it straight to the Government, which consists of five elected politicians who are obliged to consider it.

While the Prince’s political views may be questionable, Bryan Jeeves, who was born in the UK town of Croydon but has lived in Liechtenstein since 1962, believes his business acumen is unimpeachable. “In 1967 I was involved with the committee to plan Hans-Adam’s wedding,” he says. “We went up to the castle with our proposal for the ceremony but they told me they couldn’t afford it. They were so low on funds that they had just had to sell a da Vinci [Ginevra de Benci to Washington’s National Gallery of Art for $5m]. He has gone from being cash poor to having one of the biggest fortunes in Europe. If he was just a businessman, rather than being a reigning prince as well, he’d be on a par with Bill Gates.”

Jeeves is the chairman and founder of the Jeeves Group, one of approximately 250 such companies that handle trusts and fiduciaries in the country for high net-worth individuals and International Transit Persons.

Like Switzerland, Liechtenstein is not a member of the EU, but since 1995 it has been a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), which allows it to have open borders and bilateral trade agreements without Brussels impinging on its more unique aspects. such as a disproportionately powerful prince.

Being a member of the EEA also allows bankers such as Norman Oehri, the managing director of Liechtensteinische Landesbank (the oldest in the country) the freedom to acquire new clients abroad. “It’s easy in Europe,” he says, “but elsewhere in the world people haven’t heard of Liechtenstein. I have to explain it’s a country close to Switzerland and that we use the Swiss franc.”

Liechtenstein banks also offer some of the lowest company taxes in Europe (it’s estimated 70,000 companies are registered in the country; over twice the number of inhabitants). “Liechtenstein is going to continue to grow as a financial centre because it is so small,” he adds. Indeed, all Liechtenstein’s banks manage only €120bn; Julius Bär, a Swiss private bank, manages more money than this.

But Liechtenstein has only recently become known once again as a legitimate financial centre – a reputation the country’s bankers had to fight to win back after it was placed on the Financial action Task Force’s blacklist in 2000 (it remains on the OECD’s watch list with Monaco and Andorra). Today, Liechtenstein has one of the most transparent banking systems in the world. “There were some black sheep back then,” says Jeeves, “but they’ve been weeded out and it’s different now.”

Indeed, Liechtenstein is taking every action possible to prove itself, including the implementation of the Markets in Financial Instruments directive well before the global November deadline. “Liechtenstein is flexible enough to adjust to new financial situations far quicker than larger financial centres could ever hope to,” says Jeeves.

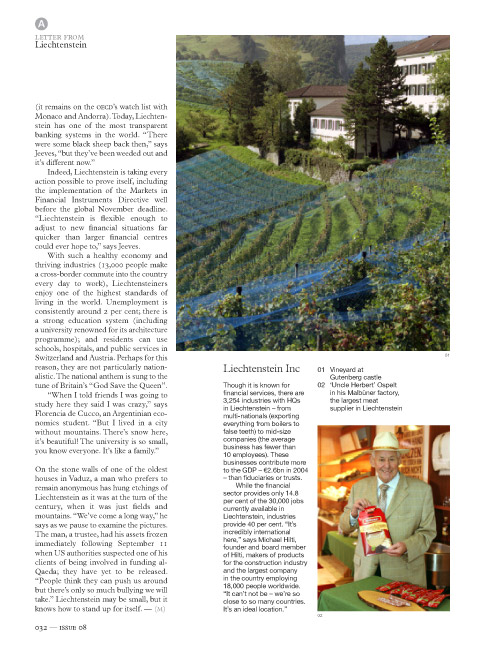

With such a healthy economy and thriving industries (13,000 people make a cross-border commute into the country every day to work), Liechtensteiners enjoy one of the highest standards of living in the world. Unemployment is consistently around 2 per cent; there is a strong education system (including a university renowned for its architecture programme); and residents can use schools, hospitals, and public services in Switzerland and Austria. Perhaps for this reason, they are not particularly nationalistic. The national anthem is sung to the tune of Britain’s “God save the Queen”.

“When I told friends I was going to study here they said I was crazy,” says Florencia de Cucco, an Argentinian economics student. “But I lived in a city without mountains. There’s snow here, it’s beautiful! The university is so small, you know everyone. It’s like a family.”

On the stone walls of one of the oldest houses in Vaduz, a man who prefers to remain anonymous has hung etchings of Liechtenstein as it was at the turn of the century, when it was just fields and mountains. “We’ve come a long way,” he says as we pause to examine the pictures. The man, a trustee, had his assets frozen immediately following September 11 when US authorities suspected one of his clients of being involved in funding Al-Qaeda; they have yet to be released. “People think they can push us around but there’s only so much bullying we will take.” Liechtenstein may be small, but it knows how to stand up for itself.