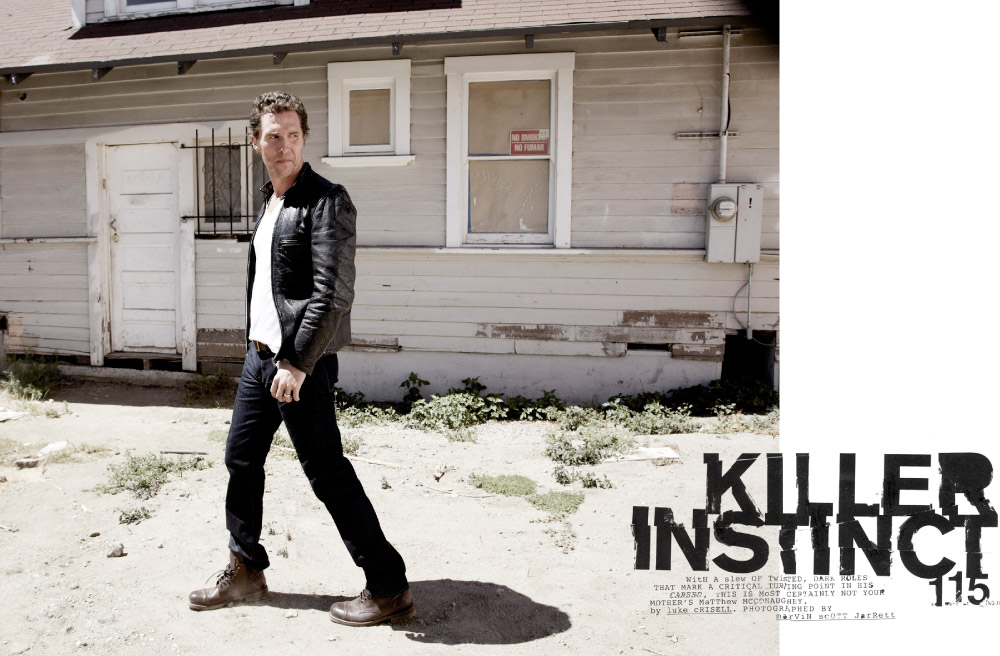

KILLER INSTINCT

WITH A SLEW OF TWISTED, DARK ROLES THAT MARK A CRITICAL TURNING POINT IN HIS CAREER, THIS IS MOST CERTAINLY NOT YOUR MOTHER’S MATTHEW MCCOUNAUGHEY.

PACING AROUND A GREENROOM at the Jimmy Kimmel Live! studios in West Hollywood, Matthew McConaughey moves from conversation to conversation like a bee in a spring garden. His publicist, makeup artist, assistant, and a couple of friends recount stories from McConaughey’s three-day wedding party at his Austin estate a few weeks earlier, where he married the Brazilian model Camila Alves, the backslaps coming as regularly as the guffaws. He owns the room, his voice rising dramatically when he’s cracking a joke and falling to a murmur when no one else needs to hear what he’s saying.

A segment producer comes in, and he and McConaughey run through the talking points of the interview. It will consist mainly of anecdotes about the wedding and his preparation for Magic Mike, the Steven Soderbergh film about male strippers that’s opening a few days later. Each question is carefully tailored to produce an answer different from those he gave on Leno the night before. No one seems to find it unusual that McConaughey is not wearing a shirt.

In a way, it’s ironic that this image of a shirtless raconteur is the one we’re starting with: This tanned, muscular paradigm of manhood who flashes caddish grins with the same ease that he maintains unwavering eye contact and who speaks in a slow, considered Texas drawl is a far cry from the McConaughey who will appear in four films over the next six months. Individually, these movies will chip away at the McConaughey stereotype, and collectively, they might just eradicate it altogether.

In addition to Magic Mike, in which McConaughey swaggers around in cowboy boots as Dallas, the owner of a seedy all-male revue in Tampa, Florida, there’s Killer Joe, a visceral, noirish thriller directed by William Friedkin (The Exorcist) which McConaughey, as the titular assassin, owns from his first scene to the batshit-crazy finale, and two films that competed at Cannes earlier this year: Jeff Nichols’s Mud, in which McConaughey plays an ex-con camping out on an island in the Mississippi; and The Paperboy, a swampy, pulpy melodrama directed by Lee Daniels (Precious), in which McConaughey disappears into his role of a closeted gay reporter. If he keeps this up, Kate Hudson, Jennifer Garner, Sarah Jessica Parker, and the rest might be waiting a very long time on their fire escapes in the rain for their man to overcome his insecurities, come to his senses, and propose to them at the critical point of Act 3. McConaughey clearly has better things to do at the moment than ponder the ethics of running off with the wedding planner.

After McConaughey and Kimmel have finished their banter (McConaughey slips on a crisp white shirt a few minutes before the segment), the actor heads through the studio and onto a makeshift basketball court set up on Hollywood Boulevard to attempt a three-point shot. The rules are simple: If he makes it, the studio audience goes home with steaks; if he doesn’t, nothing. Hundreds of fans, cheering and holding up their phones, are packed six deep behind the barriers. Across the street, by Mann’s Chinese Theater, tourist buses have parked expectantly. When he emerges the screaming intensifies, and pedestrians flock over, bolstering the crowd and stopping traffic. It’s hot and noisy as hell, and as McConaughey starts to take practice shots, another problem becomes apparent: The guy is terrible at basketball. Epicly bad. His shots crash into the backboard, clang off the rim, and, on a few particularly embarrassing occasions, airball entirely. Ten shots. Twenty. A few people in the crowd put their heads in their hands. Even the unflappable McConaughey is starting to look frustrated. Kimmel comes out, working the crowd into even more of a frenzy. The cameras start rolling, and McConaughey lines up for his one attempt, bouncing the ball on the ground with his head down, concentrating.

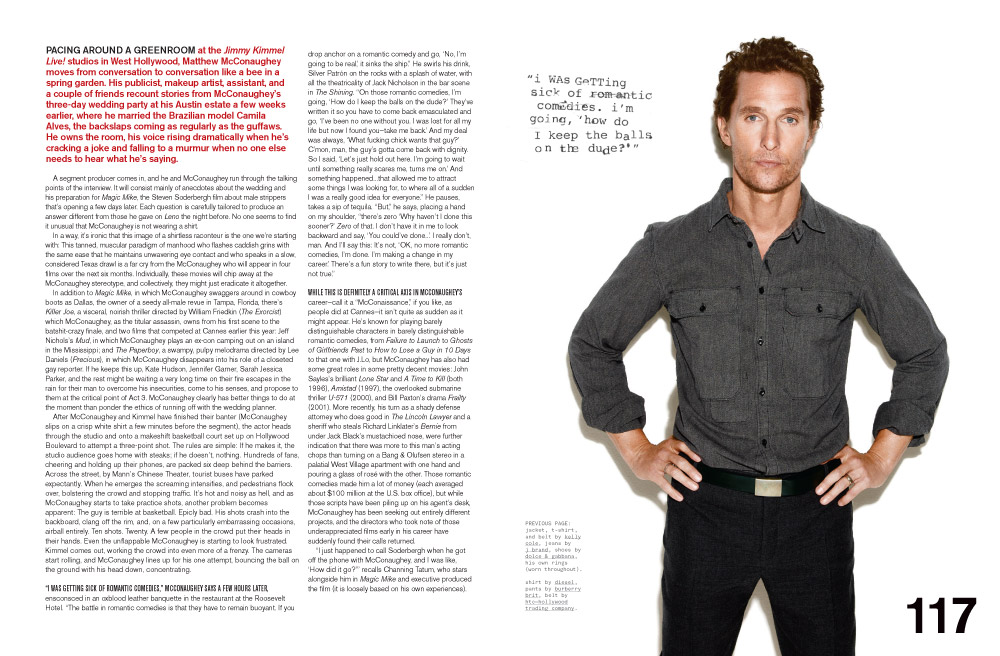

“I WAS GETTING SICK OF ROMANTIC COMEDIES,” MCCONAUGHEY SAYS A FEW HOURS LATER, ensconsced in an oxblood leather banquette in the restaurant at the Roosevelt Hotel. “The battle in romantic comedies is that they have to remain buoyant. If you drop anchor on a romantic comedy and go, ‘No, I’m going to be real,’ it sinks the ship.” He swirls his drink, Silver Patrón on the rocks with a splash of water, with all the theatricality of Jack Nicholson in the bar scene in The Shining. “On those romantic comedies, I’m going, ‘How do I keep the balls on the dude?’ They’ve written it so you have to come back emasculated and go, ‘I’ve been no one without you. I was lost for all my life but now I found you—take me back.’ And my deal was always, ‘What fucking chick wants that guy?’ C’mon, man, the guy’s gotta come back with dignity. So I said, ‘Let’s just hold out here. I’m going to wait until something really scares me, turns me on.’ And something happened...that allowed me to attract some things I was looking for, to where all of a sudden I was a really good idea for everyone.” He pauses, takes a sip of tequila. “But,” he says, placing a hand on my shoulder, “there’s zero ‘Why haven’t I done this sooner?’ Zero of that. I don’t have it in me to look backward and say, ‘You could’ve done...’ I really don’t, man. And I’ll say this: It’s not, ‘OK, no more romantic comedies, I’m done. I’m making a change in my career.’ There’s a fun story to write there, but it’s just not true.”

WHILE THIS IS DEFINITELY A CRITICAL AXIS IN MCCONAUGHEY’S career—call it a “McConaissance,” if you like, as people did at Cannes—it isn’t quite as sudden as it might appear. He’s known for playing barely distinguishable characters in barely distinguishable romantic comedies, from Failure to Launch to Ghosts of Girlfriends Past to How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days to that one with J.Lo, but McConaughey has also had some great roles in some pretty decent movies: John Sayles’s brilliant Lone Star and A Time to Kill (both 1996), Amistad (1997), the overlooked submarine thriller U-571 (2000), and Bill Paxton’s drama Frailty (2001). More recently, his turn as a shady defense attorney who does good in The Lincoln Lawyer and a sheriff who steals Richard Linklater’s Bernie from under Jack Black’s mustachioed nose, were further indication that there was more to this man’s acting chops than turning on a Bang & Olufsen stereo in a palatial West Village apartment with one hand and pouring a glass of rosé with the other. Those romantic comedies made him a lot of money (each averaged about $100 million at the U.S. box office), but while those scripts have been piling up on his agent’s desk, McConaughey has been seeking out entirely different projects, and the directors who took note of those underappreciated films early in his career have suddenly found their calls returned.

“I just happened to call Soderbergh when he got off the phone with McConaughey, and I was like, ‘How did it go?’” recalls Channing Tatum, who stars alongside him in Magic Mike and executive produced the film (it is loosely based on his own experiences). “And he’s like, ‘He said he’s in.’ And I was like, ‘Wait, what? For real? That’s crazy!’ I love and admire Matthew for that—just taking on something completely weird.” There’s one scene in which McConaughey performs a strip routine to “Calling Dr. Love,” wearing just a tasseled thong, and another where he plays the bongos—an apparent allusion to his arrest for marijuana possession in 1999, where police found him playing the bongos naked in his house. “Look, we were never going to have McConaughey in a movie where he doesn’t get naked,” Tatum says with a laugh. “I said, ‘If McConaughey’s down, we gotta have him playing the bongos at one point, and we gotta get him naked.’”

“The [striptease] dance needed to be old school— really dirty, manipulative, lusty. It’s not about quick moves, it’s about cocksmanship,” says McConaughey, who might be the only person I will ever hear use that word in my lifetime. “I was like, ‘McConaughey’”—he likes to use the third person— “‘if you don’t strip in this movie, you’re gonna regret that your whole life. It’s like that three-point shot. You gotta try and get that ball to the basket.’”

Mud, the story of a fugitive who befriends two young boys by a river in Mississippi, is a more sedate affair but just as far removed from the McConaughey stereotype. “I would have gone down this path even if the other three films he’d made that year had been romantic comedies,” says director Jeff Nichols. “I had the idea [for the film] back in 2000 and immediately started thinking about McConaughey, even then. I wrote the part for him because I needed someone who was just insanely likeable—James Garner likeable. In addition, I needed somebody who was a little off-kilter. Little did I know at the time that that very much suits Matthew’s personality.” Before the film started shooting, Nichols was in Mississippi doing preproduction when he learned that McConaughey had come down early and taken the script and a one-man tent out to the island in the river, and stayed there overnight. “I knew then: That’s the kind of guy I needed in this role.”

As much as he’s practically a stencil for the quintessential Hollywood leading man, McConaughey is also an outlier who has never set his personality to the metronome of the movie industry, despite what the more commercial spikes on his résumé may suggest. In person, he comes across as an amalgam of Wooderson, the smooth slacker he plays in Dazed and Confused, and Mick Haller, the attorney in The Lincoln Lawyer, whose unassailable self-belief and impeccable timing always seem just a wink away from parody. A few days before Nichols left for Cannes, he got a call from McConaughey, who had never been to the festival before. “He was like, ‘What’s it like over there?’” Nichols says. “And it’s so bizarre because he’s a huge movie star, and he was genuinely excited. He has true charisma. It’s not something you fake or make up or turn on: It just has to be part of who you are.”In a word, he’s charming. It’s obvious from the moment he picks me up from my hotel in a rented black Audi, shakes my hand, adjusts his sunglasses, cranks the stereo, raises his voice over the guitars of Austin band The Black Angels, and asks, “Do you like rock ’n’ roll?” As stupidly handsome as the guy is—jaw like a panther’s, piercing blue eyes—this is a hard-won self-confidence that he carries around with him, the mark of someone with nothing to hide and no reason to be anything other than himself. He’s the kind of guy who can make up a word and say it so emphatically that you don’t realize until you’re reading your notes later that it isn’t a word at all. Worse still, you just nodded and said “Yeah, totally!” when he described The Black Angels’ sound as “Vietnamatic.”

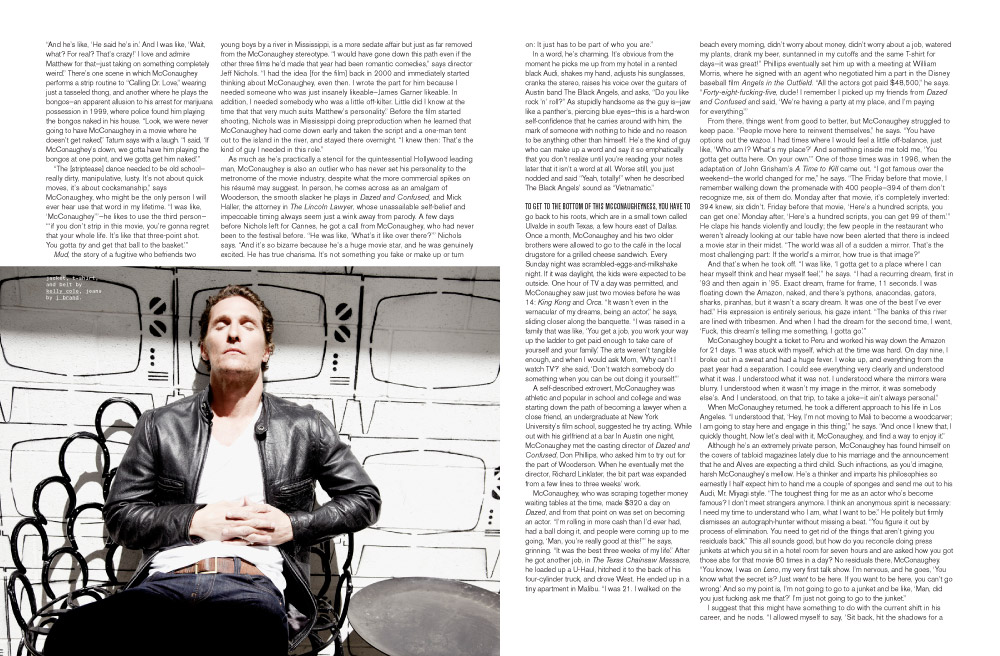

TO GET TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS MCCONAUGHEYNESS, YOU HAVE TO go back to his roots, which are in a small town called Ulvalde in south Texas, a few hours east of Dallas. Once a month, McConaughey and his two older brothers were allowed to go to the café in the local drugstore for a grilled cheese sandwich. Every Sunday night was scrambled-eggs-and-milkshake night. If it was daylight, the kids were expected to be outside. One hour of TV a day was permitted, and McConaughey saw just two movies before he was 14: King Kong and Orca. “It wasn’t even in the vernacular of my dreams, being an actor,” he says, sliding closer along the banquette. “I was raised in a family that was like, ‘You get a job, you work your way up the ladder to get paid enough to take care of yourself and your family.’ The arts weren’t tangible enough, and when I would ask Mom, ‘Why can’t I watch TV?’ she said, ‘Don’t watch somebody do something when you can be out doing it yourself.’”

A self-described extrovert, McConaughey was athletic and popular in school and college and was starting down the path of becoming a lawyer when a close friend, an undergraduate at New York University’s film school, suggested he try acting. While out with his girlfriend at a bar in Austin one night, McConaughey met the casting director of Dazed and Confused, Don Phillips, who asked him to try out for the part of Wooderson. When he eventually met the director, Richard Linklater, the bit part was expanded from a few lines to three weeks’ work.

McConaughey, who was scraping together money waiting tables at the time, made $320 a day on Dazed, and from that point on was set on becoming an actor. “I’m rolling in more cash than I’d ever had, had a ball doing it, and people were coming up to me going, ‘Man, you’re really good at this!’” he says, grinning. “It was the best three weeks of my life.” After he got another job, in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, he loaded up a U-Haul, hitched it to the back of his four-cylinder truck, and drove West. He ended up in a tiny apartment in Malibu. “I was 21. I walked on the beach every morning, didn’t worry about money, didn’t worry about a job, watered my plants, drank my beer, suntanned in my cutoffs and the same T-shirt for days—it was great!” Phillips eventually set him up with a meeting at William Morris, where he signed with an agent who negotiated him a part in the Disney baseball film Angels in the Outfield. “All the actors got paid $48,500,” he says. “Forty-eight-fucking-five, dude! I remember I picked up my friends from Dazed and Confused and said, ‘We’re having a party at my place, and I’m paying for everything.’”From there, things went from good to better, but McConaughey struggled to keep pace. “People move here to reinvent themselves,” he says. “You have options out the wazoo. I had times where I would feel a little off-balance, just like, ‘Who am I? What’s my place?’ And something inside me told me, ‘You gotta get outta here. On your own.’” One of those times was in 1996, when the adaptation of John Grisham’s A Time to Kill came out. “I got famous over the weekend—the world changed for me,” he says. “The Friday before that movie, I remember walking down the promenade with 400 people—394 of them don’t recognize me, six of them do. Monday after that movie, it’s completely inverted: 394 knew, six didn’t. Friday before that movie, ‘Here’s a hundred scripts, you can get one.’ Monday after, ‘Here’s a hundred scripts, you can get 99 of them.’” He claps his hands violently and loudly; the few people in the restaurant who weren’t already looking at our table have now been alerted that there is indeed a movie star in their midst. “The world was all of a sudden a mirror. That’s the most challenging part: If the world’s a mirror, how true is that image?”

And that’s when he took off. “I was like, ‘I gotta get to a place where I can hear myself think and hear myself feel,’” he says. “I had a recurring dream, first in ’93 and then again in ’95. Exact dream, frame for frame, 11 seconds. I was floating down the Amazon, naked, and there’s pythons, anacondas, gators, sharks, piranhas, but it wasn’t a scary dream. It was one of the best I’ve ever had.” His expression is entirely serious, his gaze intent. “The banks of this river are lined with tribesmen. And when I had the dream for the second time, I went, ‘Fuck, this dream’s telling me something, I gotta go.’”

McConaughey bought a ticket to Peru and worked his way down the Amazon for 21 days. “I was stuck with myself, which at the time was hard. On day nine, I broke out in a sweat and had a huge fever. I woke up, and everything from the past year had a separation. I could see everything very clearly and understood what it was. I understood what it was not. I understood where the mirrors were blurry. I understood when it wasn’t my image in the mirror, it was somebody else’s. And I understood, on that trip, to take a joke—it ain’t always personal.”

When McConaughey returned, he took a different approach to his life in Los Angeles. “I understood that, ‘Hey, I’m not moving to Mali to become a woodcarver; I am going to stay here and engage in this thing,’” he says. “And once I knew that, I quickly thought, Now let’s deal with it, McConaughey, and find a way to enjoy it.”

Although he’s an extremely private person, McConaughey has found himself on the covers of tabloid magazines lately due to his marriage and the announcement that he and Alves are expecting a third child. Such infractions, as you’d imagine, harsh McConaughey’s mellow. He’s a thinker and imparts his philosophies so earnestly I half expect him to hand me a couple of sponges and send me out to his Audi, Mr. Miyagi style. “The toughest thing for me as an actor who’s become famous? I don’t meet strangers anymore. I think an anonymous spirit is necessary: I need my time to understand who I am, what I want to be.” He politely but firmly dismisses an autograph-hunter without missing a beat. “You figure it out by process of elimination. You need to get rid of the things that aren’t giving you residuals back.” This all sounds good, but how do you reconcile doing press junkets at which you sit in a hotel room for seven hours and are asked how you got those abs for that movie 80 times in a day? No residuals there, McConaughey. “You know, I was on Leno, my very first talk show. I’m nervous, and he goes, ‘You know what the secret is? Just want to be here. If you want to be here, you can’t go wrong.’ And so my point is, I’m not going to go to a junket and be like, ‘Man, did you just fucking ask me that?’ I’m just not going to go to the junket.”

I suggest that this might have something to do with the current shift in his career, and he nods. “I allowed myself to say, ‘Sit back, hit the shadows for a little bit, brother, and let some things come. Let the light come in and shine. Let the truth come by. Hear it. Feel it.’”

He’s impassioned now, swirling the remaining tequila in his glass, banging his hand on the table more frequently. Eyes electric. “I think the absolute truth is around us right now,” he says. “But we don’t recognize it all the time. I mean, how could you? You have to put yourself in a place where you allow that truth that’s coming on by to go kaplunk! and drop in.”

“Don’t those kind of moments come from getting married and having children?” I ask, trying not to make it sound too much like I’m looking for life advice from Matthew McConaughey. “They’re wonderful as far as significant points in life, but they don’t redefine anything,” he replies. They give you a place where you can go, ‘I know if I go there, I can never be wrong.’ And there are very few things in life we can do that with. But they don’t redefine you. Someone asked me if this switch [from romantic comedies] had anything to do with my family,” he recalls. “I said, ‘I don’t know, but the more secure a man is at home, the more high and wide he can fly outside it.’ I’m younger now than I was before the kids. I’m honestly wilder. I’m not irresponsible, but creatively, the roof got higher.” He looks down at his glass, swirls, takes a sip. “I was curious what it was going to be like. I was a solitary dude, man. I worked. I stayed in my Airstream. I didn’t want people around. But you come home to a kid and he wants to tell you about how he crapped his pants...and I’m going, ‘This is great!’ It helps you be even younger.”

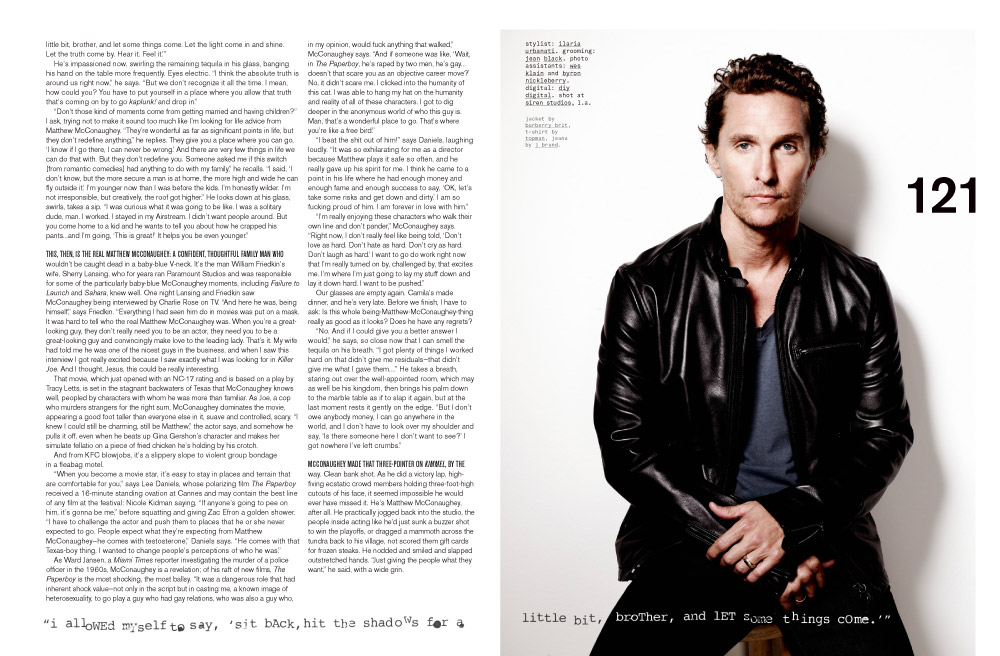

THIS, THEN, IS THE REAL MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY: A CONFIDENT, THOUGHTFUL FAMILY MAN WHO wouldn’t be caught dead in a baby-blue V-neck. It’s the man William Friedkin’s wife, Sherry Lansing, who for years ran Paramount Studios and was responsible for some of the particularly baby-blue McConaughey moments, including Failure to Launch and Sahara, knew well. One night Lansing and Friedkin saw McConaughey being interviewed by Charlie Rose on TV. “And here he was, being himself,” says Friedkin. “Everything I had seen him do in movies was put on a mask. It was hard to tell who the real Matthew McConaughey was. When you’re a great- looking guy, they don’t really need you to be an actor, they need you to be a great-looking guy and convincingly make love to the leading lady. That’s it. My wife had told me he was one of the nicest guys in the business, and when I saw this interview I got really excited because I saw exactly what I was looking for in Killer Joe. And I thought, Jesus, this could be really interesting.

That movie, which just opened with an NC-17 rating and is based on a play by Tracy Letts, is set in the stagnant backwaters of Texas that McConaughey knows well, peopled by characters with whom he was more than familiar. As Joe, a cop who murders strangers for the right sum, McConaughey dominates the movie, appearing a good foot taller than everyone else in it, suave and controlled, scary. “I knew I could still be charming, still be Matthew,” the actor says, and somehow he pulls it off, even when he beats up Gina Gershon’s character and makes her simulate fellatio on a piece of fried chicken he’s holding by his crotch.

And from KFC blowjobs, it’s a slippery slope to violent group bondage in a fleabag motel.

“When you become a movie star, it’s easy to stay in places and terrain that are comfortable for you,” says Lee Daniels, whose polarizing film The Paperboy received a 16-minute standing ovation at Cannes and may contain the best line of any film at the festival: Nicole Kidman saying, “If anyone’s going to pee on him, it’s gonna be me,” before squatting and giving Zac Efron a golden shower. “I have to challenge the actor and push them to places that he or she never expected to go. People expect what they’re expecting from Matthew McConaughey—he comes with testosterone,” Daniels says. “He comes with that Texas-boy thing. I wanted to change people’s perceptions of who he was.”As Ward Jansen, a Miami Times reporter investigating the murder of a police officer in the 1960s, McConaughey is a revelation; of his raft of new films, The Paperboy is the most shocking, the most ballsy. “It was a dangerous role that had inherent shock value—not only in the script but in casting me, a known image of heterosexuality, to go play a guy who had gay relations, who was also a guy who, in my opinion, would fuck anything that walked,” McConaughey says. “And if someone was like, ‘Wait, in The Paperboy, he’s raped by two men, he’s gay... doesn’t that scare you as an objective career move?’ No, it didn’t scare me. I clicked into the humanity of this cat. I was able to hang my hat on the humanity and reality of all of these characters. I got to dig deeper in the anonymous world of who this guy is. Man, that’s a wonderful place to go. That’s where you’re like a free bird.”

“I beat the shit out of him!” says Daniels, laughing loudly. “It was so exhilarating for me as a director because Matthew plays it safe so often, and he really gave up his spirit for me. I think he came to a point in his life where he had enough money and enough fame and enough success to say, ‘OK, let’s take some risks and get down and dirty.’ I am so fucking proud of him. I am forever in love with him.”

“I’m really enjoying these characters who walk their own line and don’t pander,” McConaughey says. “Right now, I don’t really feel like being told, ‘Don’t love as hard. Don’t hate as hard. Don’t cry as hard. Don’t laugh as hard.’ I want to go do work right now that I’m really turned on by, challenged by, that excites me. I’m where I’m just going to lay my stuff down and lay it down hard. I want to be pushed.”

Our glasses are empty again. Camila’s made dinner, and he’s very late. Before we finish, I have to ask: Is this whole being-Matthew-McConaughey-thing really as good as it looks? Does he have any regrets?

“No. And if I could give you a better answer I would,” he says, so close now that I can smell the tequila on his breath. “I got plenty of things I worked hard on that didn’t give me residuals—that didn’t give me what I gave them....” He takes a breath, staring out over the well-appointed room, which may as well be his kingdom, then brings his palm down to the marble table as if to slap it again, but at the last moment rests it gently on the edge. “But I don’t owe anybody money, I can go anywhere in the world, and I don’t have to look over my shoulder and say, ‘Is there someone here I don’t want to see?’ I got nowhere I’ve left crumbs.”

MCCONAUGHEY MADE THAT THREE-POINTER ON KIMMEL, BY THE way. Clean bank shot. As he did a victory lap, high- fiving ecstatic crowd members holding three-foot-high cutouts of his face, it seemed impossible he would ever have missed it. He’s Matthew McConaughey, after all. He practically jogged back into the studio, the people inside acting like he’d just sunk a buzzer shot to win the playoffs, or dragged a mammoth across the tundra back to his village, not scored them gift cards for frozen steaks. He nodded and smiled and slapped outstretched hands. “Just giving the people what they want,” he said, with a wide grin.