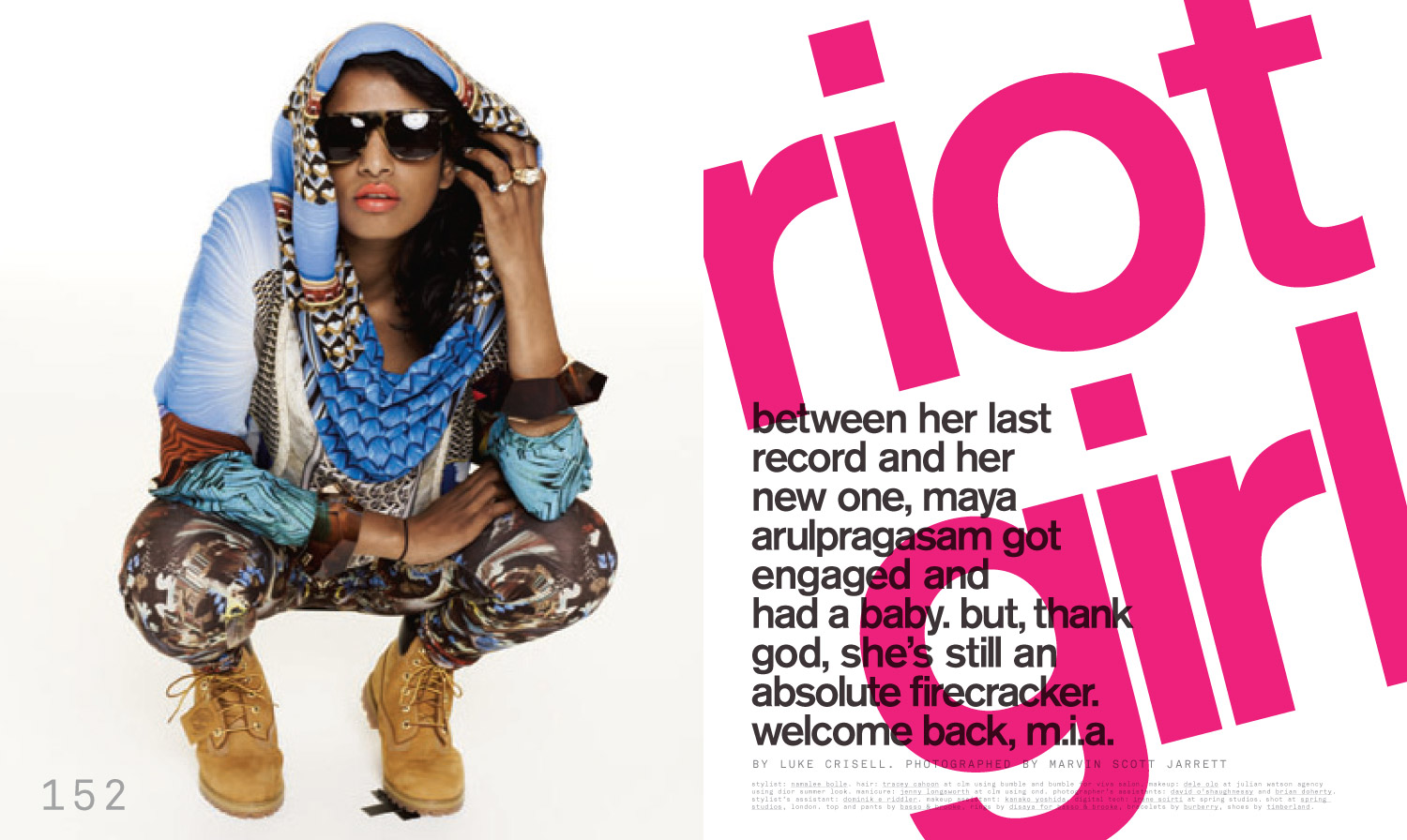

RIOT GIRL

BETWEEN HER LAST RECORD AND HER NEW ONE, MAYA ARULPRAGASAM GOT ENGAGED AND HAD A BABY. BUT, THANK GOD, SHE’S STILL AN ABSOLUTE FIRECRACKER. WELCOME BACK, M.I.A.

NOTTING HILL, AN area of West London distinguished perhaps only by its boringness, does not seem to much suit M.I.A. It’s a blustery afternoon in late spring, and we’re walking between rows of imposing Georgian houses, once white, now weathered to different shades of ivory, like old piano keys, toward Portobello Road. A few blue tarpaulins flap loudly in the wind, slapping against rickety metal frames; across the street, a man is shouting about how cheap his potatoes are. The sky is a swirl of varying grays like burnished pewter. “Every time I come back here, it’s changed even more,” says M.I.A., who is wearing tight-fitting black pants and an oversized slate-gray shirt. The only indications that she might be, or has ever been, one of the more fashion-forward women in music are her shoes—towering black heels with gold-metal toes—and her nails, which are painted in tribal yellows and greens; when she moves her hands quickly, it’s as though they’re surrounded by fireflies. “I used to work at a shop called Euphoria down there”—she gestures toward a street in front of us—“with Cassette Playa [the designer Carri Munden]. But the shop has gone now, and so’ve all my friends. All the young creative people can’t afford to be here anymore.” We turn onto Portobello Road and go into the kind of fashion- able restaurant that prefers to serve its wine by the carafe, with mosaic floors,a zinc bar, and lots of expensive wood, and take a booth in the far corner of the back room, which is otherwise empty. M.I.A. glances at the menu for about 10 seconds, then puts it down and pushes it across the table. The waiter comes over. “I’m gonna get the lamb chops and a Bloody Mary,” she says, casting her eyes around the room, a sea of walnut. “Seems like that kinda day.”

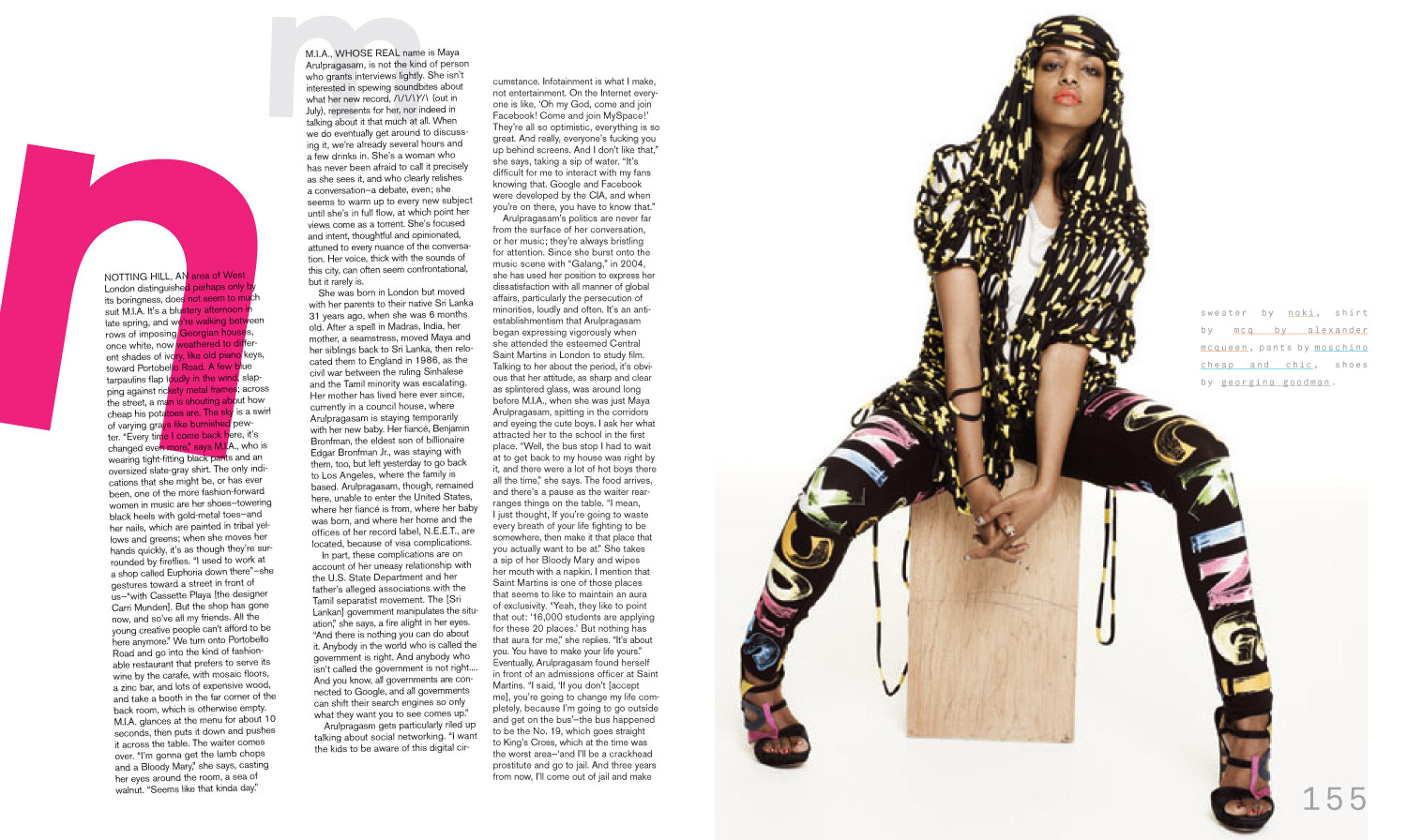

M.I.A., WHOSE REAL name is Maya Arulpragasam, is not the kind of person who grants interviews lightly. She isn’t interested in spewing soundbites about what her new record, /\/\/\Y/\ (out in July), represents for her, nor indeed in talking about it that much at all. When we do eventually get around to discussing it, we’re already several hours and a few drinks in. She’s a woman who has never been afraid to call it precisely as she sees it, and who clearly relishes a conversation a debate, even; she seems to warm up to every new subject until she’s in full flow, at which point her views come as a torrent. She’s focused and intent, thoughtful and opinionated, attuned to every nuance of the conversation. Her voice, thick with the sounds of this city, can often seem confrontational, but it rarely is.

She was born in London but moved with her parents to their native Sri Lanka 31 years ago, when she was 6 months old. After a spell in Madras, India, her mother, a seamstress, moved Maya and her siblings back to Sri Lanka, then relocated them to England in 1986, as the civil war between the ruling Sinhalese and the Tamil minority was escalating. Her mother has lived here ever since, currently in a council house, where Arulpragasam is staying temporarily with her new baby. Her fiancé, Benjamin Bronfman, the eldest son of billionaire Edgar Bronfman Jr., was staying with them, too, but left yesterday to go back to Los Angeles, where the family is based. Arulpragasam, though, remained here, unable to enter the United States, where her fiancé is from, where her baby was born, and where her home and the offices of her record label, N.E.E.T., are located, because of visa complications.

In part, these complications are on account of her uneasy relationship with the U.S. State Department and her father’s alleged associations with the Tamil separatist movement. The [Sri Lankan] government manipulates the situation,” she says, a fire alight in her eyes. “And there is nothing you can do about it. Anybody in the world who is called the government is right. And anybody who isn’t called the government is not right.... And you know, all governments are connected to Google, and all governments can shift their search engines so only what they want you to see comes up.”

Arulpragasm gets particularly riled up talking about social networking. “I want the kids to be aware of this digital circumstance. Infotainment is what I make, not entertainment. On the Internet everyone is like, ‘Oh my God, come and join Facebook! Come and join MySpace!’ They’re all so optimistic, everything is so great. And really, everyone’s fucking you up behind screens. And I don’t like that,” she says, taking a sip of water. “It’s difficult for me to interact with my fans knowing that. Google and Facebook were developed by the CIA, and when you’re on there, you have to know that.”

Arulpragasam’s politics are never far from the surface of her conversation, or her music; they’re always bristling for attention. Since she burst onto the music scene with “Galang,” in 2004, she has used her position to express her dissatisfaction with all manner of global affairs, particularly the persecution of minorities, loudly and often. It’s an anti-establishmentism that Arulpragasam began expressing vigorously when she attended the esteemed Central Saint Martins in London to study film. Talking to her about the period, it’s obvious that her attitude, as sharp and clear as splintered glass, was around long before M.I.A., when she was just Maya Arulpragasam, spitting in the corridors and eyeing the cute boys. I ask her what attracted her to the school in the first place. “Well, the bus stop I had to wait at to get back to my house was right by it, and there were a lot of hot boys there all the time,” she says. The food arrives, and there’s a pause as the waiter rearranges things on the table. “I mean, I just thought, If you’re going to waste every breath of your life fighting to be somewhere, then make it that place that you actually want to be at.” She takes a sip of her Bloody Mary and wipes her mouth with a napkin. I mention that Saint Martins is one of those places that seems to like to maintain an aura of exclusivity. “Yeah, they like to point that out: ‘16,000 students are applying for these 20 places.’ But nothing has that aura for me,” she replies. “It’s about you. You have to make your life yours.” Eventually, Arulpragasam found herself in front of an admissions officer at Saint Martins. “I said, ‘If you don’t [accept me], you’re going to change my life completely, because I’m going to go outside and get on the bus’—the bus happened to be the No. 19, which goes straight to King’s Cross, which at the time was the worst area—‘and I’ll be a crackhead prostitute and go to jail. And three years from now, I’ll come out of jail and make the best film.” She got the place, one of the 20. “I was the only brown person,” she says. “So everyone was like, ‘She’s going to make films about arranged marriage.’ That bothered me so much! There was so much going on in my reality! I was always going out to L.A. ’cause my cousin lived there, and she knew all the Bloods and Crips. So I was hanging out with her, having crazy times, and then I’d come back and be like, ‘I hung out with Tupac last week!’ And nobody knew who he was!” She grew increasingly frustrated with her class and proceeded to rebel against it. “They’d be like, ‘Yes well, I’m making a film about feminism,’” she says, adopting a posh accent. “I’m like, ‘Feminism! Have you been to South Central?!’ It’s like, ‘You’re making films about issues? Let’s not even get into talking about issues because I win! I got about a million!’” She’s almost shouting, she’s so excited. “And no one in my college wanted to know about rap musicor rap culture. I was like, ‘Yeah, but that’s current and relevant and that shit is happening, people!’ It was the most progres- sive and interesting thing that was happening at the time.” She tucks a leg up under herself. “I was a pretty feisty chick, if you know what I mean.”

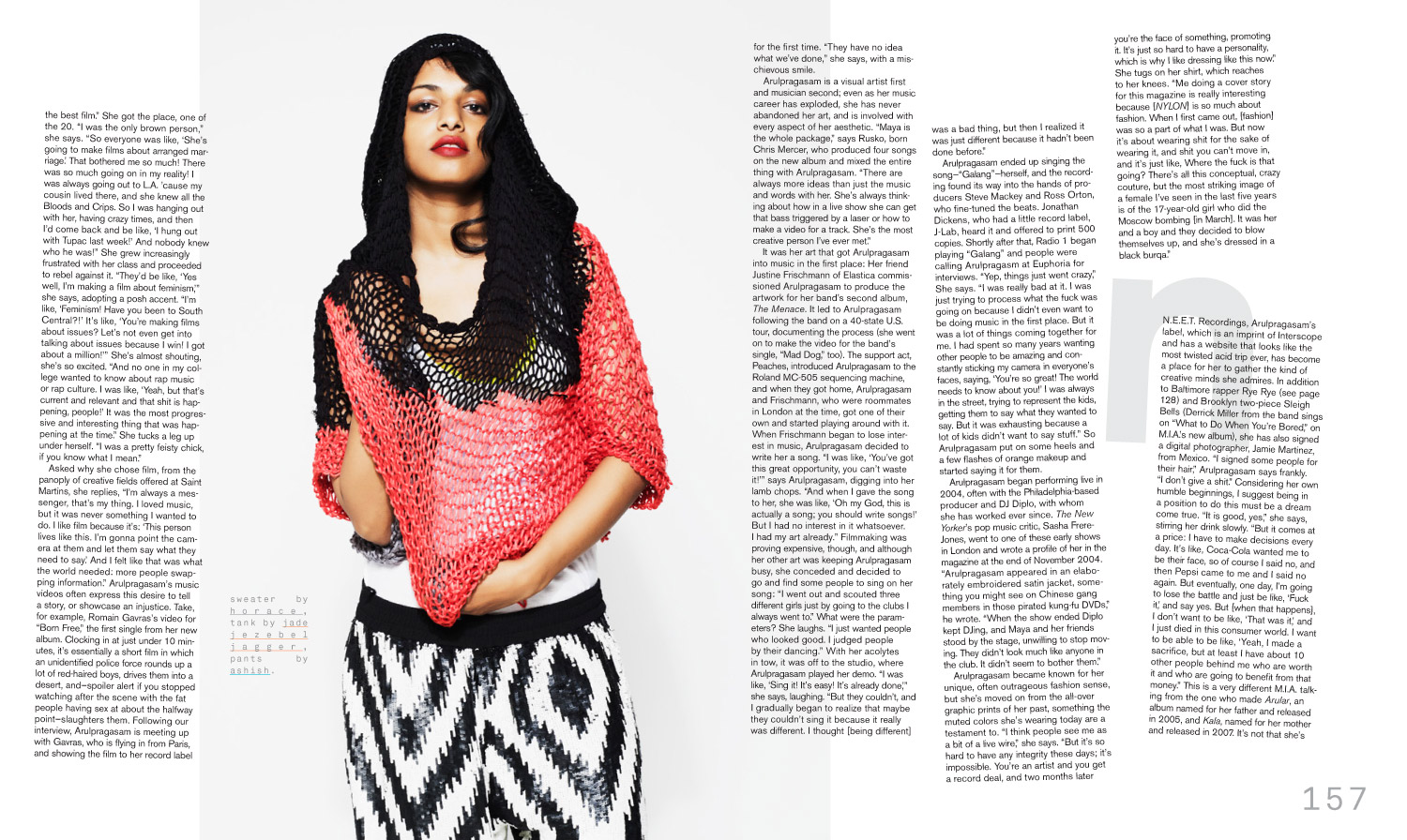

Asked why she chose film, from the panoply of creative fields offered at Saint Martins, she replies, “I’m always a messenger, that’s my thing. I loved music, but it was never something I wanted to do. I like film because it’s: ‘This person lives like this. I’m gonna point the camera at them and let them say what they need to say.’ And I felt like that was what the world needed: more people swapping information.” Arulpragasam’s music videos often express this desire to tell a story, or showcase an injustice. Take, for example, Romain Gavras’s video for “Born Free,” the first single from her new album. Clocking in at just under 10 minutes, it’s essentially a short film in which an unidentified police force rounds up a lot of red-haired boys, drives them into a desert, and—spoiler alert if you stopped watching after the scene with the fat people having sex at about the halfway point—slaughters them. Following our interview, Arulpragasam is meeting up with Gavras, who is flying in from Paris, and showing the film to her record label the first time. “They have no idea what we’ve done,” she says, with a mischievous smile.

Arulpragasam is a visual artist first and musician second; even as her music career has exploded, she has never abandoned her art, and is involved with every aspect of her aesthetic. “Maya is the whole package,” says Rusko, born Chris Mercer, who produced four songs on the new album and mixed the entire thing with Arulpragasam. “There are always more ideas than just the music and words with her. She’s always thinking about how in a live show she can get that bass triggered by a laser or how to make a video for a track. She’s the most creative person I’ve ever met.”

It was her art that got Arulpragasam into music in the first place: Her friend Justine Frischmann of Elastica commissioned Arulpragasam to produce the artwork for her band’s second album, The Menace. It led to Arulpragasam following the band on a 40-state U.S. tour, documenting the process (she went on to make the video for the band’s single, “Mad Dog,” too). The support act, Peaches, introduced Arulpragasam to the Roland MC-505 sequencing machine, and when they got home, Arulpragasam and Frischmann, who were roommates in London at the time, got one of their own and started playing around with it. When Frischmann began to lose interest in music, Arulpragasam decided to write her a song. “I was like, ‘You’ve got this great opportunity, you can’t waste it!’” says Arulpragasam, digging into her lamb chops. “And when I gave the song to her, she was like, ‘Oh my God, this is actually a song; you should write songs!’ But I had no interest in it whatsoever. I had my art already.” Filmmaking was proving expensive, though, and although her other art was keeping Arulpragasam busy, she conceded and decided togo and find some people to sing on her song: “I went out and scouted three different girls just by going to the clubs I always went to.” What were the param- eters? She laughs. “I just wanted people who looked good. I judged peopleby their dancing.” With her acolytes in tow, it was off to the studio, where Arulpragasam played her demo. “I was like, ‘Sing it! It’s easy! It’s already done,’” she says, laughing. “But they couldn’t, and I gradually began to realize that maybe they couldn’t sing it because it really was different. I thought [being different] was a bad thing, but then I realized it was just different because it hadn’t been done before.”

Arulpragasam ended up singing the song—“Galang”—herself, and the recording found its way into the hands of producers Steve Mackey and Ross Orton, who fine-tuned the beats. Jonathan Dickens, who had a little record label, J-Lab, heard it and offered to print 500 copies. Shortly after that, Radio 1 began playing “Galang” and people were calling Arulpragasm at Euphoria for interviews. “Yep, things just went crazy,” She says. “I was really bad at it. I was just trying to process what the fuck was going on because I didn’t even want to be doing music in the first place. But it was a lot of things coming together for me. I had spent so many years wanting other people to be amazing and constantly sticking my camera in everyone’s faces, saying, ‘You’re so great! The world needs to know about you!’ I was always in the street, trying to represent the kids, getting them to say what they wanted to say. But it was exhausting because alot of kids didn’t want to say stuff.” So Arulpragasam put on some heels and a few flashes of orange makeup and started saying it for them.

Arulpragasam began performing live in 2004, often with the Philadelphia-based producer and DJ Diplo, with whom she has worked ever since. The New Yorker’s pop music critic, Sasha Frere-Jones, went to one of these early shows in London and wrote a profile of her in the magazine at the end of November 2004. “Arulpragasam appeared in an elaborately embroidered satin jacket, something you might see on Chinese gang members in those pirated kung-fu DVDs,” he wrote. “When the show ended Diplo kept DJing, and Maya and her friends stood by the stage, unwilling to stop moving. They didn’t look much like anyone in the club. It didn’t seem to bother them.”

Arulpragasam became known for her unique, often outrageous fashion sense, but she’s moved on from the all-over graphic prints of her past, something the muted colors she’s wearing today are a testament to. “I think people see me as a bit of a live wire,” she says. “But it’s so hard to have any integrity these days; it’s impossible. You’re an artist and you get a record deal, and two months later you’re the face of something, promoting it. It’s just so hard to have a personality, which is why I like dressing like this now.” She tugs on her shirt, which reaches to her knees. “Me doing a cover story for this magazine is really interesting because [NYLON] is so much about fashion. When I first came out, [fashion] was so a part of what I was. But nowit’s about wearing shit for the sake of wearing it, and shit you can’t move in, and it’s just like, Where the fuck is that going? There’s all this conceptual, crazy couture, but the most striking image of a female I’ve seen in the last five years is of the 17-year-old girl who did the Moscow bombing [in March]. It was her and a boy and they decided to blow themselves up, and she’s dressed in a black burqa.”

N.E.E.T. Recordings, Arulpragasam’s label, which is an imprint of Interscope and has a website that looks like the most twisted acid trip ever, has become a place for her to gather the kind of creative minds she admires. In addition to Baltimore rapper Rye Rye (see page 128) and Brooklyn two-piece Sleigh Bells (Derrick Miller from the band sings on “What to Do When You’re Bored,” on M.I.A.’s new album), she has also signed a digital photographer, Jamie Martinez, from Mexico. “I signed some people for their hair,” Arulpragasam says frankly. “I don’t give a shit.” Considering her own humble beginnings, I suggest being ina position to do this must be a dream come true. “It is good, yes,” she says, stirring her drink slowly. “But it comes at a price: I have to make decisions every day. It’s like, Coca-Cola wanted me to be their face, so of course I said no, and then Pepsi came to me and I said no again. But eventually, one day, I’m going to lose the battle and just be like, ‘Fuck it,’ and say yes. But [when that happens], I don’t want to be like, ‘That was it,’ and I just died in this consumer world. I want to be able to be like, ‘Yeah, I made a sacrifice, but at least I have about 10 other people behind me who are worth it and who are going to benefit from that money.” This is a very different M.I.A. talking from the one who made Arular, an album named for her father and released in 2005, and Kala, named for her mother and released in 2007. It’s not that she’s lost her passion, or even her vehemence, but she’s definitely grown up and seems to have come to terms with her popularity. It shouldn’t be forgotten that many people first heard of M.I.A. after three of her tracks were featured in Danny Boyle’s Oscar favorite Slumdog Millionaire, in 2008; her every Twitter post is now analyzed around the world (which could be another reason for her temporary stasis: “I Twitter politically pissed-off shit”). She’s been covered by Rihanna, sampled by Jay-Z, and nominated for a Grammy (she performed at the awards show on her baby’s due date in a dress that was mostly see-through). In short, she’s kind of a big deal. “It’s not that I’m going to do [an advertising campaign] and go and buy myself a yacht,” she says. “But if I do it and then can cultivate 10 other brains into being free to do what they want to do...that’s a good thing.”

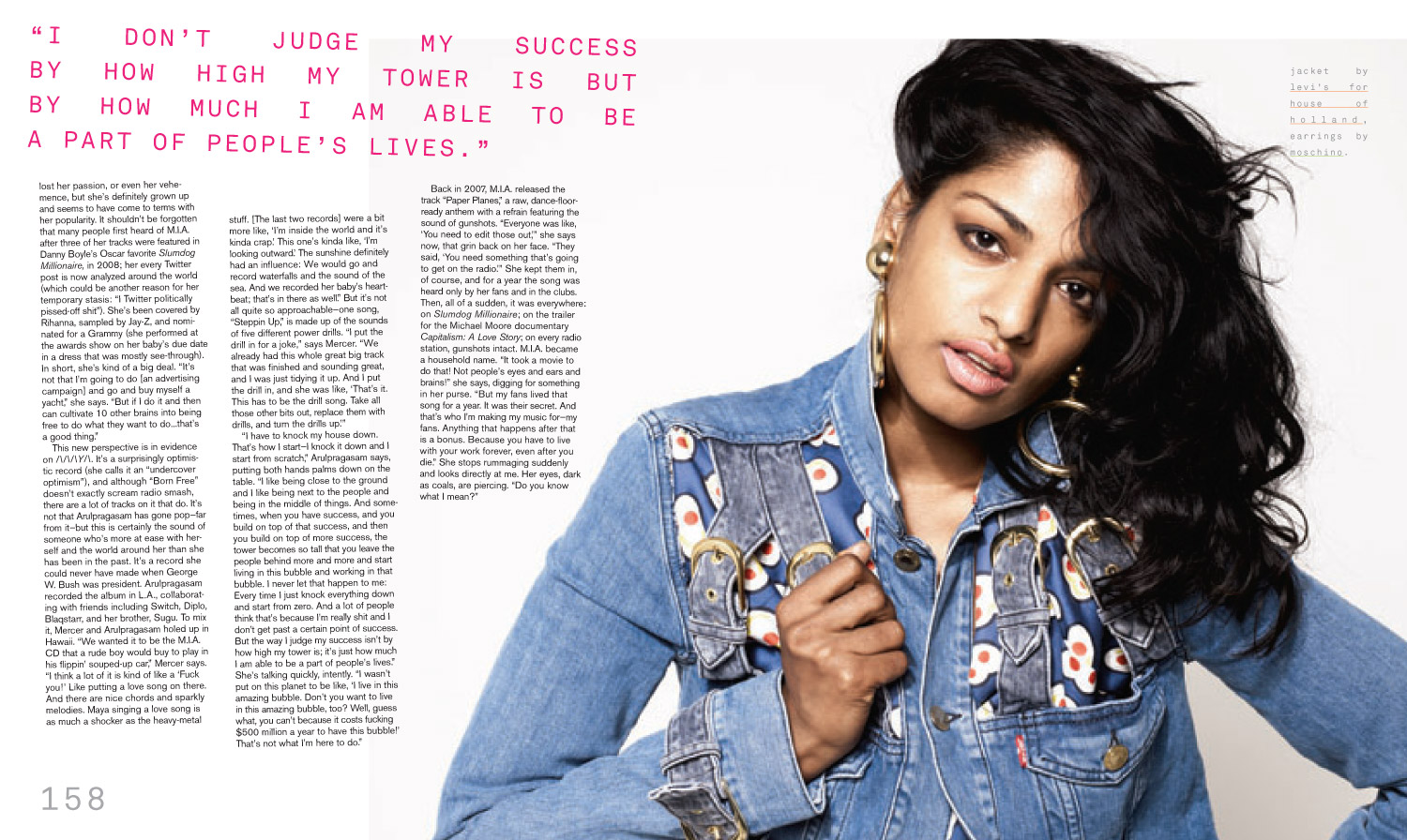

This new perspective is in evidence on /\/\/\Y/\. It’s a surprisingly optimistic record (she calls it an “undercover optimism”), and although “Born Free” doesn’t exactly scream radio smash, there are a lot of tracks on it that do. It’s not that Arulpragasam has gone pop—far from it—but this is certainly the sound of someone who’s more at ease with herself and the world around her than she has been in the past. It’s a record she could never have made when George W. Bush was president. Arulpragasam recorded the album in L.A., collaborating with friends including Switch, Diplo, Blaqstarr, and her brother, Sugu. To mix it, Mercer and Arulpragasam holed up in Hawaii. “We wanted it to be the M.I.A. CD that a rude boy would buy to play in his flippin’ souped-up car,” Mercer says. “I think a lot of it is kind of like a ‘Fuck you!’ Like putting a love song on there. And there are nice chords and sparkly melodies. Maya singing a love song is as much a shocker as the heavy-metal stuff. [The last two records] were a bit more like, ‘I’m inside the world and it’s kinda crap.’ This one’s kinda like, ‘I’m looking outward.’ The sunshine definitely had an influence: We would go and record waterfalls and the sound of the sea. And we recorded her baby’s heart- beat; that’s in there as well.” But it’s not all quite so approachable—one song, “Steppin Up,” is made up of the sounds of five different power drills. “I put the drill in for a joke,” says Mercer. “We already had this whole great big track that was finished and sounding great, and I was just tidying it up. And I put the drill in, and she was like, ‘That’s it. This has to be the drill song. Take all those other bits out, replace them with drills, and turn the drills up.’”

“I have to knock my house down. That’s how I start—I knock it down and I start from scratch,” Arulpragasam says, putting both hands palms down on the table. “I like being close to the ground and I like being next to the people and being in the middle of things. And some- times, when you have success, and you build on top of that success, and then you build on top of more success, the tower becomes so tall that you leave the people behind more and more and start living in this bubble and working in that bubble. I never let that happen to me: Every time I just knock everything down and start from zero. And a lot of people think that’s because I’m really shit and I don’t get past a certain point of success. But the way I judge my success isn’t by how high my tower is; it’s just how much I am able to be a part of people’s lives.” She’s talking quickly, intently. “I wasn’t put on this planet to be like, ‘I live in this amazing bubble. Don’t you want to live in this amazing bubble, too? Well, guess what, you can’t because it costs fucking $500 million a year to have this bubble!’ That’s not what I’m here to do.”

BACK IN 2007, M.I.A. released the track “Paper Planes,” a raw, dance-floor-ready anthem with a refrain featuring the sound of gunshots. “Everyone was like, ‘You need to edit those out,’” she says now, that grin back on her face. “They said, ‘You need something that’s going to get on the radio.’” She kept them in, of course, and for a year the song was heard only by her fans and in the clubs. Then, all of a sudden, it was everywhere: on Slumdog Millionaire; on the trailer for the Michael Moore documentary Capitalism: A Love Story; on every radio station, gunshots intact. M.I.A. became a household name. “It took a movie to do that! Not people’s eyes and ears and brains!” she says, digging for something in her purse. “But my fans lived that song for a year. It was their secret. And that’s who I’m making my music for—my fans. Anything that happens after that is a bonus. Because you have to live with your work forever, even after you die.” She stops rummaging suddenly and looks directly at me. Her eyes, dark as coals, are piercing. “Do you know what I mean?”