THE COLLECTOR

IN THE FOURTEEN YEARS SINCE NIGO STARTED A BATHING APE, HE HAS AMASSED A LOT OF INCREDIBLE STUFF, AND A LOT OF VERY FAMOUS FRIENDS, BUT THE SECRET OF HIS SUCCESS REMAINS A SECRET.

THE SKY OVER TOKYO is as dark as slate. Occasionally, a fork of lightning tears through it as if it were velvet, and the rain is pouring down in almost Biblical quantities. The torrent pummels the ubiquitous clear plastic umbrellas of the commuters who hurry quickly home, heads bowed, along the sidewalks, and beats on the tops of the rickety old red-and-white Toyota taxi cabs which skip like minnows through the streets. In a hilly, affluent part of Shibuya, a ward to the Southwest of the city, the water runs in sinewy rivulets down tangled, narrow roads and gushes under the wheels of the customized Mercedes, Aston Martins, and Escalades which are parked outside the homes and offices of some of the city’s most successful business people. Here, at the end of a small alley, are the unmarked A Bathing Ape offices, and in a white-walled room lit by fluorescent lights the rap music coming from the stereo is being all but drowned out by the thunder that crashes, deep and sonorous, outside.

“Damn, that’s some mad crazy weather out there!” exclaims Kanye West, a Frappuccino in hand, looking askance at the window through oversize sunglasses. West is here to work on some tracks in the Bape Sounds recording studio upstairs, but Nigo, a friend of his and the founder and director of A Bathing Ape isn’t here yet, so, like everyone else, West is waiting for him, occasionally shooting an expectant glance at the door.

There are eight racks sagging heavy with clothes in the room; the fall/winter Bape collection, and one wall is lined with shelves, stacked with the brand’s accessories for the new season. On the floor are hundreds of sneakers in new color-ways. The members of West’s not inconsiderable entourage are in their element. They try on hoodies, jackets, coats, sweatshirts, hats, even backpacks, and hold up the sneakers reverentially, as if they were priceless relics. “This shit is mad fresh ’Ye!” yells West’s close friend and co-manager Don C. as he pulls on a black baseball-style jacket that is about two sizes too big for him. “Maaad fresh.”

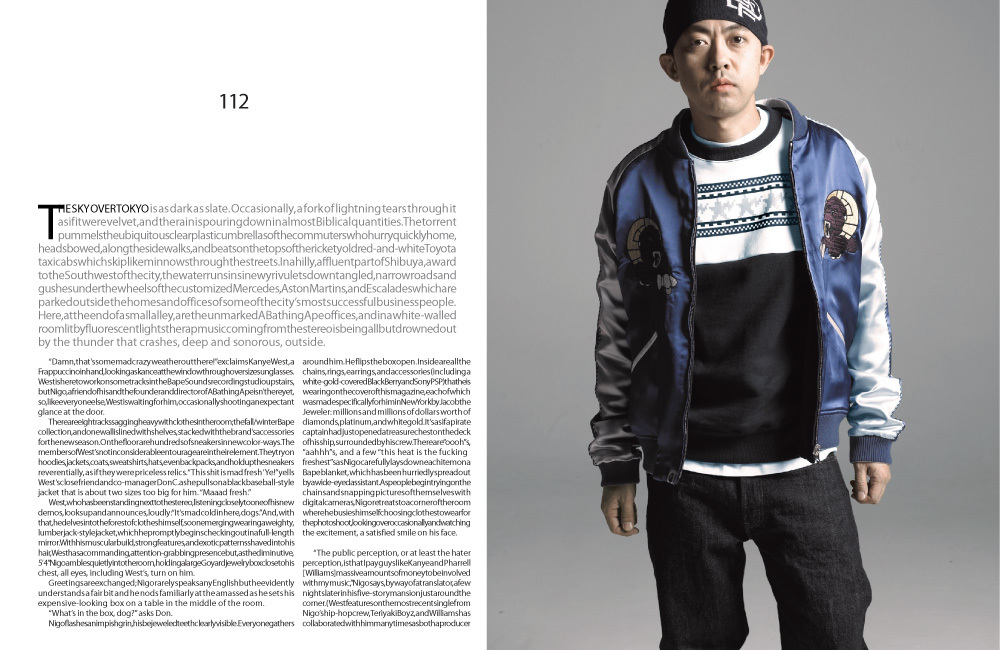

West, who has been standing next to the stereo, listening closely to one of his new demos, looks up and announces, loudly: “It’s mad cold in here, dogs.” And, with that, he delves into the forest of clothes himself, soon emerging wearing a weighty, lumberjack style jacket, which he promptly begins checking out in a full-length mirror. With his muscular build, strong features, and exotic patterns shaved into his hair, West has a commanding, attention-grabbing presence but, as the diminutive, 5’4” Nigo ambles quietly into the room, holding a large Goyard jewelry box close to his chest, all eyes, including West’s, turn on him.

Greetings are exchanged; Nigo rarely speaks any English but he evidently understands a fair bit and he nods familiarly at the amassed as he sets his expensive-looking box on a table in the middle of the room.

“What’s in the box, dog?” asks Don. Nigo flashes an impish grin, his bejeweled teeth clearly visible. Everyone gathers around him. He flips the box open. Inside are all the chains, rings, earrings, and accessories (including a white-gold-covered BlackBerry and SonyPSP) that he is wearing on the cover of this magazine, each of which was made specifically for him in New York by Jacob the Jeweler: millions and millions of dollars worth of diamonds, platinum, and white gold. It’s as if a pirate captain had just opened a treasure chest on the deck of his ship, surrounded by his crew. There are “oooh”s, “aahhh”s, and a few “this heat is the fucking freshest”s as Nigo carefully lays down each item on a Bape blanket, which has been hurriedly spread out by a wide-eyed assistant. As people begin trying on the chains and snapping pictures of themselves with digital cameras, Nigo retreats to a corner of the room where he busies himself choosing clothes to wear for the photo shoot, looking over occasionally and watching the excitement, a satisfied smile on his face.

“THE PUBLIC PERCEPTION, or at least the hater perception, is that I pay guys like Kanye and Pharrell [Williams] massive amounts of money to be involved with my music,” Nigo says, by way of a translator, a few nights later in his five-story mansion just around the corner. (West features on the most recent single from Nigo’s hip-hop crew, Teriyaki Boyz, and Williams has collaborated with him many times as both a producer and a guest vocalist. The two also have a clothing line together, called Billionaire Boys Club). “But in reality they are genuinely interested in working with me. People in Japan think that because I have a lot of money I can buy my way into anything I want to be in, but in reality it’s based on personal relationships. I think people find it hard to understand how I have such a great lifestyle off of selling some clothes...” he trails off, wringing his hands as he thinks about it. “It’s as if there must be something behind all of this... but I don’t have secret, hidden businesses; there aren’t side hustles going on here,” he continues, earnestly. “I devote all of my energy to the clothing business and the money that comes out of it. This brand is the second biggest independent brand in Japan—everything is very tightly controlled. I know how much stock there is of every item in every country that I have a store. It’s just really successful.”

THAT’S AN UNDERSTATEMENT: Since Nigo (born Tomoaki Nagao) started selling screen-printed T-shirts, out of a little boutique called Nowhere that he shared with his friend Jun Takahashi (the founder of Undercover) on a deserted back-street of Harajuku 14 years ago, A Bathing Ape has grown into an international success story, one that reveals more about the impeccable business acumen of its owner than it does the quality of the product. And although Nigo said in an interview in 2000 that he had no interest in the American market, he says he is now, increasingly, drawn to the U.S. by its potential consumer base, by the people there that he admires, and by a feeling of dislocation in his home country. “There are a lot of people who understand what I’m doing in America,” he told me once. “I’ve always been well-received there, while in Japan they try to ignore me as much as possible. It’s strange because people in Japan respect people overseas respecting me more than they respect their own judgment. That attitude is so frustrating, so I’m always trying to do stuff to fuck with it.” By controlling every possible facet of the brand’s evolution—from the light fittings in the directly-managed stores to the collaborations with high-profile musicians—cultivating celebrity connections and, in the early days of the brand, carefully limiting the supply of his product, Nigo has built an empire and, in the process, invented a new consumer subculture that the kids are, quite literally, lining up to buy into.

One sticky, humid afternoon in Hong Kong, I spoke to some of those kids, many of who had been waiting through the night to secure a limited-edition T-shirt celebrating the one year anniversary of the Bape store there, and to meet Nigo, who was due to sign some of them for a few hours. There were still two hours to go before Nigo was supposed to arrive. Inside the store a small army of employees, standing in a semi- circle, were being debriefed by the manager, who was guiding them through a complex flow chart on a large poster board.

“So have you found out how he does it?” a guy wearing a Bape cap, T-shirt, jeans, and sneakers asked me, excitedly.

Does what? I asked .

“How he works his magic.”

What magic is that?

“It’s like he prints money. So much money...” he replied, smiling. Then the line started moving and he filed slowly into spend $80 on a T-shirt. He had been waiting for 16 hours.

Such an obsessive following is unique in the fashion industry. But then Nigo has always positioned himself outside of this, and in so doing has become a celebrity in his own right. He makes no claims to be a fashion designer. He is, rather, a curator, a collector, and, for all the media coverage of him (a wall on an upper floor of his house is covered with the hundreds of magazine covers he has been on: “They’re not all there—I’m running out of room,” he said), something of an enigma.

IN THE FIVE days I spent with Nigo, it occasionally seemed as though he was trying to speak through his possessions, but it was the moments that he wasn’t talking to me at all that seemed to reveal the most about his character: On almost all his public engagements at the moment, Nigo is accompanied by a man dressed in a monkey suit, who occasionally interviews him, for a reality show on MTV Japan called NIGOLDENEYE. On one occasion, in the VIP room of the Bape store in Hong Kong, Nigo looked across at the 6-foot-tall monkey sitting next to him, who was jabbering at a TV camera, and seemed, for a split second, bemused. As if, even for him, the situation was a little ridiculous. He shook his head almost imperceptibly, picked up a marker pen, and went back to signing T-shirts. On another, at a private dinner held in his honor in one of Hong Kong’s best restaurants, with spectacular views over the city’s famous harbor, he slumped low in his chair and played with his BlackBerry for much of the time, as if he really would rather just be back in his hotel suite, with room service and cable TV. But I also caught glimpses of the other side of his character: a boyish cheerfulness that seemed to come out when he was in his home, surrounded by his stuff. Once, when he was waiting for a photo crew from an interiors magazine to set up their equipment in his living room, he put on a fiberglass Mr. Peanut costume from the ’40s, that was about 4 feet high, and wandered around wearing it, waving his arms and laughing. Then he took it off and started looking at his newest lunchbox, a tin one with a Pigs in Space design, that had arrived that day.“ Pigs in Space!” he said under his breath, nodding his head gently as if remembering their escapades. Still smiling he put it back in its place, carefully, and brushed a fleck of dust from it. He seemed, for a moment, like the loneliest guy in the world.

“I DON’T FEEL like I’ve done anything to hide my lifestyle,” he says one evening in the main room of his house in Shibuya. In the background, jazz music is playing quietly from a top-of-the-range Bang and Olufsen sound system. “I’m happy to show people things. I’ve always been on TV a lot, and Japanese TV carries a lot of power. But when I know a celebrity that I’ve become friends with for whatever reason, usually nothing connected to my business, I don’t necessarily want them to wear my stuff on TV. I would rather they wore it in private. I don’t want to have relationships with someone where it’s like a two-way street, where I benefit from knowing lots of these kinds of people; I’d rather keep those elements quiet. Take David Beckham,” and here he gestures to a photo of himself with the soccer star on the wall behind us (it is one of about 100 on display showing Nigo with various celebrities), “he’s someone who has got a very powerful image. If he wears a Bape shirt it would take the brand in a totally different direction. It’s so interesting for me to meet someone who’s that successful and good at what he does, but I don’t want it to turn into a business deal. I’m not saying I don’t want them to wear my clothes, but those are friendships for me.” Whether or not this is really the case (celebrities— from Japanese boy band megastar Takuya Kimura to D. J.s such as James Lavelle—have been wearing Bape prominently in the media practically since its inception), it’s in keeping with Nigo’s insistence, in every one of our interviews, that his actions are never motivated by business, or by money. “I don’t ever want to do something because it makes business sense,” he says, after fetching us espressos (in little Bape espresso cups) from the kitchen. “I just want to do the things I want to do, and then hopefully they’ll turn out to be successful. The crucial thing to understand about me is that the only value that money has for me is what I can do with it. I’m a collector—I just think about what I can buy, what things I can get. For me, getting new things inspires me to think of something else to do. There’s a lot of value in the stuff I have…” here he looks around the room at the millions of dollars worth of possessions gathered around him, “but I’m not interested in accumulating money, at all.” We’re sitting at a large, metal-topped Jean Prouvé table (“there are only two of these in the world” he tells me, proudly), and in fact the room is almost entirely furnished with original, priceless, Prouvé furniture. Vintage toys—such as a Felix doll from the 1920s,and a very old, very odd, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves—sit on Prouvé shelves (and every other available surface); seven Louis Vuitton soccer balls in their original leather cases (specially commissioned for the 2004 World Cup in France) hang from a Prouvé room divider; a stack of vintage film posters almost a foot high sits on another huge Prouvé dining table behind us, on top of which is an uncut sheet of $2 bills from the U.S. Treasury; a third dining table is covered in neatly arranged vintage lunch boxes, one of his latest interests (opening one, he shows me the little Thermos flask inside: “They’re worth so much more with these,” he says, grinning), and two daybeds stand near a window, covered in vintage stuffed toys. I point out a particularly exquisite child’s school desk he has in the corner, next to a full-size version. Beaming, he fetches a Prouvé catalog from atop one of the three Prouvé dressers in the room. (He has three copies of the catalog, itself a collector’s item, on display in all of the three languages it was published in.) He opens it to a picture of the same style of child’s desk, but the one in the catalogue is dilapidated. “You see, they couldn’t even get a good one for the book!” he exclaims, excitedly. Why don’t you have any of these? I ask, pointing to a picture of a particularly rare variety of Prouvé school desk. He looks at me, as if surprised. “I have four of those in storage,” he says. Later that night, he shows me his wine collection in the basement. Twelve glass-fronted, temperature controlled cabinets house countless bottles. One cabinet is solely devoted to the wine of Château Mouton Rothschild—renowned for producing some of the 20th century’s most revered and valuable vintages. He has a bottle from every year since they started producing it in 1945. To put this small part of his collection in context, one bottle of Château Mouton Rothschild 1945 vintage sold for $57,000 at an auction in Beverly Hills in 2006.

NIGO COLLECTS WITH such ardor and fastidiousness that, on more than one occasion, it appears to be an obsession. Once, when we arrived back at his house at the end of the day, he had four packages waiting for him, which, he said, is typical. Quickly, he moved a small collection of snow-globes from a prominent shelf and then, as he unwrapped each package (various Mr. Peanut toys he had chosen at a vintage toy fair in Atlanta, Georgia, the previous month) he put them on the now-free shelf, and arranged them lovingly. His possessions—including collections of Star Wars toys, Eames furniture (often borrowed for museum exhibitions), guitars, denim, Gucci, Kaws art, wine, and cars mostly unrivalled by any personal collector anywhere in the world—have come to define him, in the public eye, and the media, as an eccentric.

One cool afternoon in Tokyo, as we ate lunch in a private (a push of a button on the wall turned the glass opaque), wood-paneled room in the Bape café in Harajuku, he brought up the subject of his possessions. “I had a call from my parents last night because they saw on the news that there was smoke coming from the top of my building,” he said, while meticulously cutting his chicken, into geometric, bite-size pieces before beginning to eat it. In addition to his mansion in Shibuya, Nigo has a penthouse in Rappongi Hills, an apartment that once had the most expensive rent of any in Tokyo. “It turned out the air conditioning was broken but it got me thinking about what I would save if there was ever a fire…” He paused here to summon a petrified-looking waiter and send back his plate of French fries, which hadn’t been prepared to his liking. I asked him what he would save if he could just take one thing.

“If I could only take one there would be no point,” he said, a contemplative look on his face. “If I lost everything in a fire I would want to give up. I wouldn’t know what to do with myself. Collecting is the gasoline for my engine.”

For Nigo, his possessions, and the act of accumulating things around him, are not just hobbies, or the benefits of success, they’re his life. “He has someone who comes in to clean his house,” a close friend of his told me, “but they don’t touch his stuff. That’s one of the things that makes him the happiest—arranging and displaying his stuff.” So overt is Nigo’s materialism, and so honest is he about his desire to acquire possessions, that his collections can be seen to be an index to his mind. He will talk animatedly and extensively about his belongings but clams up when he’s asked personal questions. It’s an unnerving temporality.

“What are you most proud of?” I asked him once in the back of a large SUV, when he was watching rap videos on one of the cars’ DVD players.

He laughed nervously. “I don’t really know.”

“What makes you the saddest?”

“I don’t really think of negative things, I’m not very reflective.”

“Looking back, would you have done anything differently?”

"Not at all. I think that in each point in time I’ve made the best decision I could have made at that time. As far as I’m concerned, now is always the best time, and I’m always working to make that the case. It’s like my collections are most valuable to me, but maybe after I’m dead other people will see them as valuable, too.” He paused and looked out of the window at the crowds moving slowly through Harajuku. “You know, even if there are people hating on me at the moment, when they look back at history in 10 years they’ll have to admit that what I was doing was interesting, even if they weren’t into it at the time.”