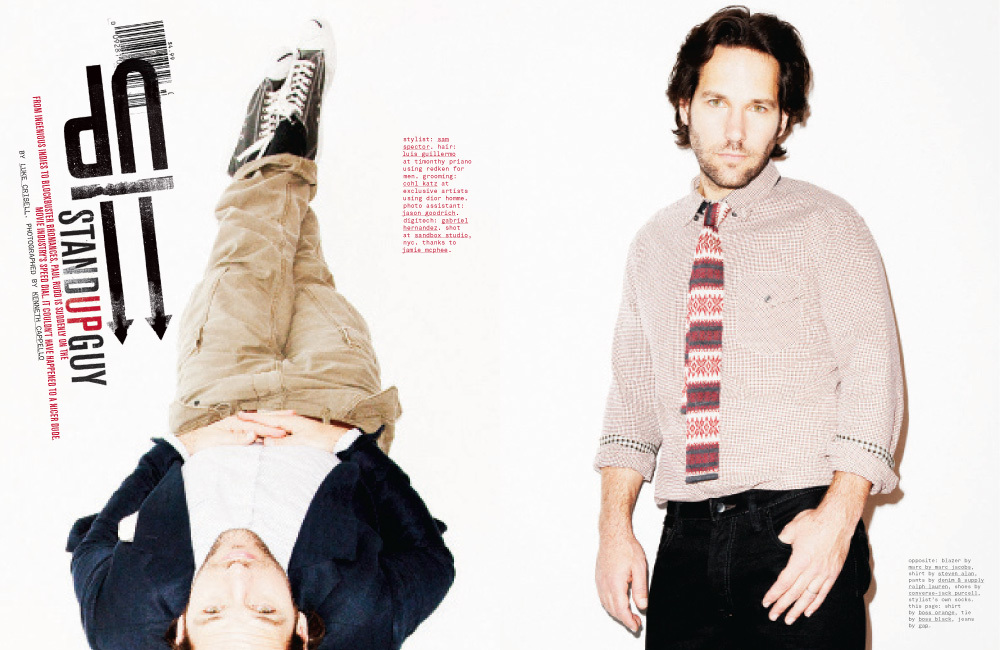

STAND UP GUY

FROM INGENIUOUS INDIES TO BLOCKBUSTER BROMANCES, PAUL RUDD IS SUDDENLY ON THE MOVIE INDUSTRY’S SPEED DIAL. IT COULDN’T HAVE HAPPENED TO A NICER DUDE.

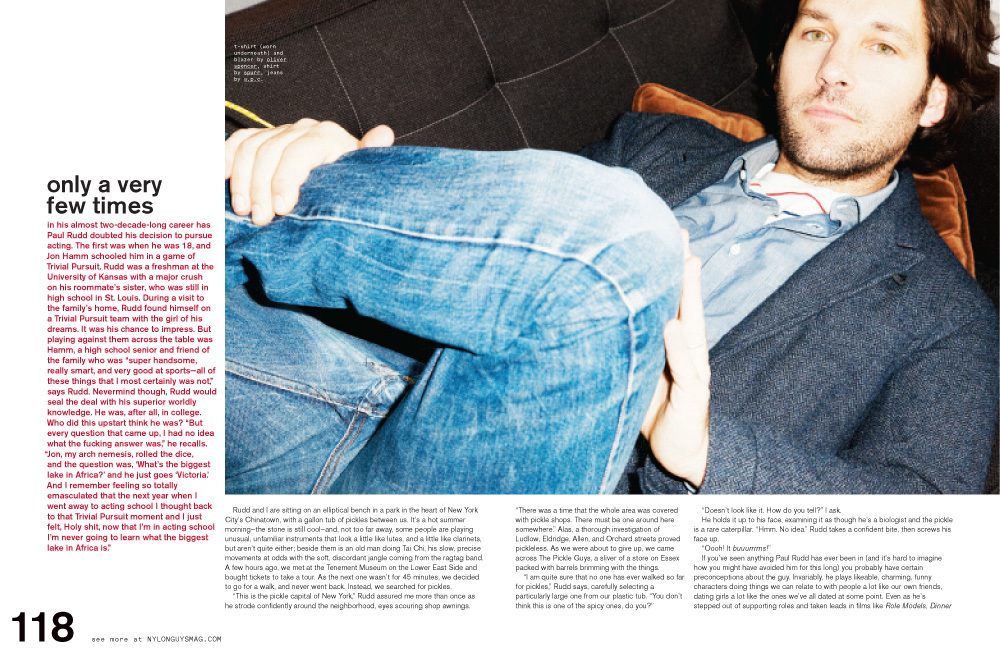

ONLY A VERY FEW TIMES in his almost two-decade-long career has Paul Rudd doubted his decision to pursue acting. The first was when he was 18, and Jon Hamm schooled him in a game of Trivial Pursuit. Rudd was a freshman at the University of Kansas with a major crush on his roommate’s sister, who was still in high school in St. Louis. During a visit to the family’s home, Rudd found himself on a Trivial Pursuit team with the girl of his dreams. It was his chance to impress. But playing against them across the table was Hamm, a high school senior and friend of the family who was “super handsome, really smart, and very good at sports—all of these things that I most certainly was not,” says Rudd. Nevermind though, Rudd would seal the deal with his superior worldly knowledge. He was, after all, in college. Who did this upstart think he was? “But every question that came up, I had no idea what the fucking answer was,” he recalls. “Jon, my arch nemesis, rolled the dice, and the question was, ‘What’s the biggest lake in Africa?’ and he just goes ‘Victoria.’ And I remember feeling so totally emasculated that the next year when I went away to acting school I thought back to that Trivial Pursuit moment and I just felt, Holy shit, now that I’m in acting school I’m never going to learn what the biggest lake in Africa is.”

Rudd and I are sitting on an elliptical bench in a park in the heart of New York City’s Chinatown, with a gallon tub of pickles between us. It’s a hot summer morning—the stone is still cool—and, not too far away, some people are playing unusual, unfamiliar instruments that look a little like lutes, and a little like clarinets, but aren’t quite either; beside them is an old man doing Tai Chi, his slow, precise movements at odds with the soft, discordant jangle coming from the ragtag band. A few hours ago, we met at the Tenement Museum on the Lower East Side and bought tickets to take a tour. As the next one wasn’t for 45 minutes, we decided to go for a walk, and never went back. Instead, we searched for pickles. “This is the pickle capital of New York,” Rudd assured me more than once as he strode confidently around the neighborhood, eyes scouring shop awnings.

“There was a time that the whole area was covered with pickle shops. There must be one around here somewhere.” Alas, a thorough investigation of Ludlow, Eldridge, Allen, and Orchard streets proved pickleless. As we were about to give up, we came across The Pickle Guys, a sliver of a store on Essex packed with barrels brimming with the things.

“I am quite sure that no one has ever walked so far for pickles,” Rudd says, carefully selecting a particularly large one from our plastic tub. “You don’t think this is one of the spicy ones, do you?”

“Doesn’t look like it. How do you tell?” I ask.

He holds it up to his face, examining it as though he’s a biologist and the pickle is a rare caterpillar. “Hmm. No idea.” Rudd takes a confident bite, then screws his face up.

“Oooh! It buuurrrrns!”

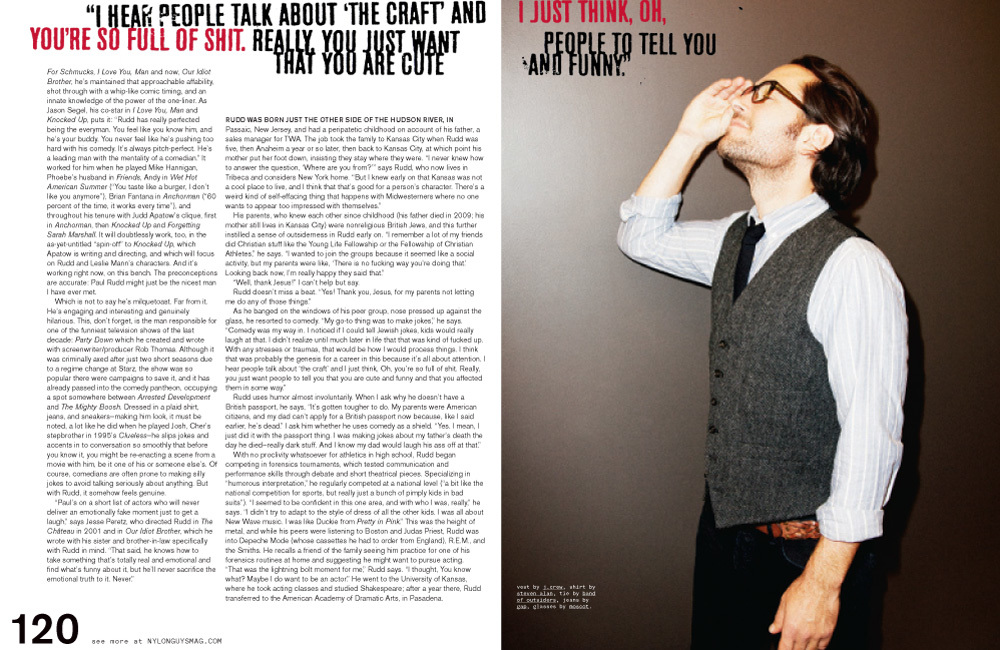

If you’ve seen anything Paul Rudd has ever been in (and it’s hard to imagine how you might have avoided him for this long) you probably have certain preconceptions about the guy. Invariably, he plays likeable, charming, funny characters doing things we can relate to with people a lot like our own friends, dating girls a lot like the ones we’ve all dated at some point. Even as he’s stepped out of supporting roles and taken leads in films like Role Models, Dinner For Schmucks, I Love You, Man and now, Our Idiot Brother, he’s maintained that approachable affability, shot through with a whip-like comic timing, and an innate knowledge of the power of the one-liner. As Jason Segel, his co-star in I Love You, Man and Knocked Up, puts it: “Rudd has really perfected being the everyman. You feel like you know him, and he’s your buddy. You never feel like he’s pushing too hard with his comedy. It’s always pitch-perfect. He’s a leading man with the mentality of a comedian.” It worked for him when he played Mike Hannigan, Phoebe’s husband in Friends, Andy in Wet Hot American Summer (“You taste like a burger, I don’t like you anymore”), Brian Fantana in Anchorman (“60 percent of the time, it works every time”), and throughout his tenure with Judd Apatow’s clique, first in Anchorman, then Knocked Up and Forgetting Sarah Marshall. It will doubtlessly work, too, in the as-yet-untitled “spin-off” to Knocked Up, which Apatow is writing and directing, and which will focus on Rudd and Leslie Mann’s characters. And it’s working right now, on this bench. The preconceptions are accurate: Paul Rudd might just be the nicest man I have ever met.

Which is not to say he’s milquetoast. Far from it. He’s engaging and interesting and genuinely hilarious. This, don’t forget, is the man responsible for one of the funniest television shows of the last decade: Party Down which he created and wrote with screenwriter/producer Rob Thomas. Although it was criminally axed after just two short seasons due to a regime change at Starz, the show was so popular there were campaigns to save it, and it has already passed into the comedy pantheon, occupying a spot somewhere between Arrested Development and The Mighty Boosh. Dressed in a plaid shirt, jeans, and sneakers—making him look, it must be noted, a lot like he did when he played Josh, Cher’s stepbrother in 1995’s Clueless—he slips jokes and accents in to conversation so smoothly that before you know it, you might be re-enacting a scene from a movie with him, be it one of his or someone else’s. Of course, comedians are often prone to making silly jokes to avoid talking seriously about anything. But with Rudd, it somehow feels genuine.

“Paul’s on a short list of actors who will never deliver an emotionally fake moment just to get a laugh,” says Jesse Peretz, who directed Rudd in The Château in 2001 and in Our Idiot Brother, which he wrote with his sister and brother-in-law specifically with Rudd in mind. “That said, he knows how to take something that’s totally real and emotional and find what’s funny about it, but he’ll never sacrifice the emotional truth to it. Never.”

RUDD WAS BORN JUST THE OTHER SIDE OF THE HUDSON RIVER, IN Passaic, New Jersey, and had a peripatetic childhood on account of his father, a sales manager for TWA. The job took the family to Kansas City when Rudd was five, then Anaheim a year or so later, then back to Kansas City, at which point his mother put her foot down, insisting they stay where they were. “I never knew how to answer the question, ‘Where are you from?’” says Rudd, who now lives in Tribeca and considers New York home. “But I knew early on that Kansas was not a cool place to live, and I think that that’s good for a person’s character. There’s a weird kind of self-effacing thing that happens with Midwesterners where no one wants to appear too impressed with themselves.”

His parents, who knew each other since childhood (his father died in 2009; his mother still lives in Kansas City) were nonreligious British Jews, and this further instilled a sense of outsiderness in Rudd early on. “I remember a lot of my friends did Christian stuff like the Young Life Fellowship or the Fellowship of Christian Athletes,” he says. “I wanted to join the groups because it seemed like a social activity, but my parents were like, ‘There is no fucking way you’re doing that.’ Looking back now, I’m really happy they said that.”

“Well, thank Jesus!” I can’t help but say.

Rudd doesn’t miss a beat. “Yes! Thank you, Jesus, for my parents not letting me do any of those things.”

As he banged on the windows of his peer group, nose pressed up against the glass, he resorted to comedy. “My go-to thing was to make jokes,” he says. “Comedy was my way in. I noticed if I could tell Jewish jokes, kids would really laugh at that. I didn’t realize until much later in life that that was kind of fucked up. With any stresses or traumas, that would be how I would process things. I think that was probably the genesis for a career in this because it’s all about attention. I hear people talk about ‘The Craft’ and I just think, Oh, you’re so full of shit. Really, you just want people to tell you that you are cute and funny and that you affected them in some way.”

Rudd uses humor almost involuntarily. When I ask why he doesn’t have a British passport, he says, “It’s gotten tougher to do. My parents were American citizens, and my dad can’t apply for a British passport now because, like I said earlier, he’s dead.” I ask him whether he uses comedy as a shield. “Yes. I mean, I just did it with the passport thing. I was making jokes about my father’s death the day he died—really dark stuff. And I know my dad would laugh his ass off at that.”

With no proclivity whatsoever for athletics in high school, Rudd began competing in forensics tournaments, which tested communication and performance skills through debate and short theatrical pieces. Specializing in “humorous interpretation,” he regularly competed at a national level (“a bit like the national competition for sports, but really just a bunch of pimply kids in bad suits”). “I seemed to be confident in this one area, and with who I was, really,” he says. “I didn’t try to adapt to the style of dress of all the other kids. I was all about New Wave music. I was like Duckie from Pretty in Pink.” This was the height of metal, and while his peers were listening to Boston and Judas Priest, Rudd was into Depeche Mode (whose cassettes he had to order from England), R.E.M., and the Smiths. He recalls a friend of the family seeing him practice for one of his forensics routines at home and suggesting he might want to pursue acting.

“That was the lightning bolt moment for me,” Rudd says. “I thought, You know what? Maybe I do want to be an actor.” He went to the University of Kansas, where he took acting classes and studied Shakespeare; after a year there, Rudd transferred to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, in Pasadena.

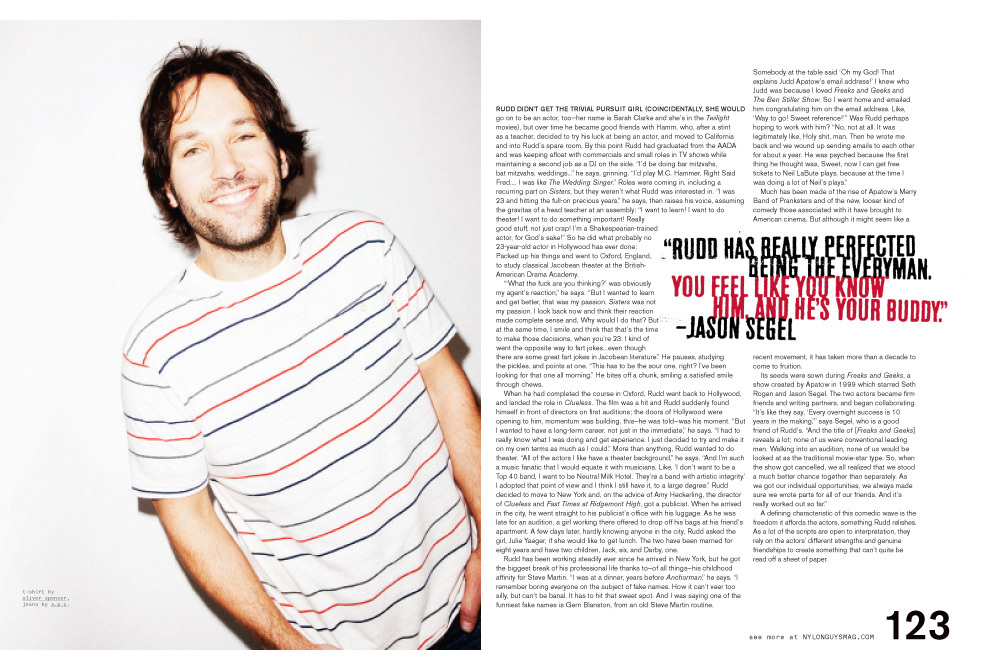

RUDD DIDN’T GET THE TRIVIAL PURSUIT GIRL (COINCIDENTALLY, SHE WOULD go on to be an actor, too—her name is Sarah Clarke and she’s in the Twilight movies), but over time he became good friends with Hamm, who, after a stint as a teacher, decided to try his luck at being an actor, and moved to California and into Rudd’s spare room. By this point Rudd had graduated from the AADA and was keeping afloat with commercials and small roles in TV shows while maintaining a second job as a DJ on the side. “I’d be doing bar mitzvahs, bat mitzvahs, weddings...” he says, grinning. “I’d play M.C. Hammer, Right Said Fred.... I was like The Wedding Singer.” Roles were coming in, including a recurring part on Sisters, but they weren’t what Rudd was interested in. “I was 23 and hitting the full-on precious years,” he says, then raises his voice, assuming the gravitas of a head teacher at an assembly: “I want to learn! I want to do theater! I want to do something important! Really good stuff, not just crap! I’m a Shakespearian-trained actor, for God’s sake!” So he did what probably no 23-year-old actor in Hollywood has ever done: Packed up his things and went to Oxford, England, to study classical Jacobean theater at the British- American Drama Academy.

“‘What the fuck are you thinking?’ was obviously my agent’s reaction,” he says. “But I wanted to learn and get better, that was my passion. Sisters was not my passion. I look back now and think their reaction made complete sense and, Why would I do that? But at the same time, I smile and think that that’s the time to make those decisions, when you’re 23. I kind of went the opposite way to fart jokes...even though there are some great fart jokes in Jacobean literature.” He pauses, studying the pickles, and points at one. “This has to be the sour one, right? I’ve been looking for that one all morning.” He bites off a chunk, smiling a satisfied smile through chews.

When he had completed the course in Oxford, Rudd went back to Hollywood, and landed the role in Clueless. The film was a hit and Rudd suddenly found himself in front of directors on first auditions; the doors of Hollywood were opening to him, momentum was building, this—he was told—was his moment. “But I wanted to have a long-term career, not just in the immediate,” he says. “I had to really know what I was doing and get experience. I just decided to try and make it on my own terms as much as I could.” More than anything, Rudd wanted to do theater. “All of the actors I like have a theater background,” he says. “And I’m such a music fanatic that I would equate it with musicians. Like, ‘I don’t want to be a Top 40 band, I want to be Neutral Milk Hotel. They’re a band with artistic integrity.’ I adopted that point of view and I think I still have it, to a large degree.” Rudd decided to move to New York and, on the advice of Amy Heckerling, the director of Clueless and Fast Times at Ridgemont High, got a publicist. When he arrived in the city, he went straight to his publicist’s office with his luggage. As he was late for an audition, a girl working there offered to drop off his bags at his friend’s apartment. A few days later, hardly knowing anyone in the city, Rudd asked the girl, Julie Yaeger, if she would like to get lunch. The two have been married for eight years and have two children, Jack, six, and Darby, one.

Rudd has been working steadily ever since he arrived in New York, but he got the biggest break of his professional life thanks to—of all things—his childhood affinity for Steve Martin. “I was at a dinner, years before Anchorman,” he says. “I remember boring everyone on the subject of fake names. How it can’t veer too silly, but can’t be banal. It has to hit that sweet spot. And I was saying one of the funniest fake names is Gern Blanston, from an old Steve Martin routine. Somebody at the table said ‘Oh my God! That explains Judd Apatow’s email address!’ I knew who Judd was because I loved Freaks and Geeks and The Ben Stiller Show. So I went home and emailed him congratulating him on the email address. Like, ‘Way to go! Sweet reference!’” Was Rudd perhaps hoping to work with him? “No, not at all. It was legitimately like, Holy shit, man. Then he wrote me back and we wound up sending emails to each other for about a year. He was psyched because the first thing he thought was, Sweet, now I can get free tickets to Neil LaBute plays, because at the time I was doing a lot of Neil’s plays.”

Much has been made of the rise of Apatow’s Merry Band of Pranksters and of the new, looser kind of comedy those associated with it have brought to American cinema. But although it might seem like a recent movement, it has taken more than a decade to come to fruition. Its seeds were sown during Freaks and Geeks, a show created by Apatow in 1999 which starred Seth Rogen and Jason Segel. The two actors became firm friends and writing partners, and began collaborating. “It’s like they say, ‘Every overnight success is 10 years in the making,’” says Segel, who is a good friend of Rudd’s. “And the title of [Freaks and Geeks] reveals a lot; none of us were conventional leading men. Walking into an audition, none of us would be looked at as the traditional movie-star type. So, when the show got cancelled, we all realized that we stood a much better chance together than separately. As we got our individual opportunities, we always made sure we wrote parts for all of our friends. And it’s really worked out so far.”

A defining characteristic of this comedic wave is the freedom it affords the actors, something Rudd relishes. As a lot of the scripts are open to interpretation, they rely on the actors’ different strengths and genuine friendships to create something that can’t quite be read off a sheet of paper.

“I know that other directors had worked this way— Christopher Guest for example—but it seemed so fresh to me,” Rudd says. “I remember when I worked on Friends, if an actor had a different idea for a joke, you would have to do it as written in the run-through then pitch it and re-do it. It was so structured—there was no way anything was going to be organic. I remember thinking, I don’t think I’m good in this setting—I can’t make this work.” He picks up the tub of pickles for a closer look. Nothing in the rather sorry selection remaining is of interest. “This way, I get to create a character or add dialogue or completely improvise and play off people and that’s such a thrilling way to work. It’s great to be able to go through something like that with somebody. It’s the one thing I always thought would be so great about being in a band: Your friends are there and you get to go on that ride together. Whereas when you’re an actor and your career starts to go, really only you know what it’s like. It’s not as fun unless you get to share it.”

“There’s a really strong level of friendship and trust, and you know everyone’s on the same team,” says Segel. “We have a sort of ‘no pride agreement’ where we give each other scripts and appreciate notes and constructive criticism from our friends, and that’s what makes our scripts turn out the way they do. We have respect for each other as actors. We write each other parts, and when we cast them, especially for our friends, we know our friends know their abilities better than we do, better than we could ever write for them. And that’s where the improv element comes in: We trust that they’re all gonna come in and nail it.”

But although Rudd is a fully paid-up member of this new frat pack and has written movies of his own (including Role Models, a “total rewrite” of an existing script, Big Brothers), his work is by no means limited to genres with the prefix ‘bro.’ In the independent film Our Idiot Brother, which premiered at Sundance, and was bought by Harvey Weinstein, he is in almost every scene as Ned, a lovable, dishelved organic farmer who sells pot to a uniformed—uniformed!—police officer and then, on his release, couch surfs around the apartments of his three sisters (Zooey Deschanel, Elizabeth Banks, and Emily Mortimer), in New York. He’s naïve but not stupid, and his observations cut to the core of their lives with an acuity reserved for the innocent. Jesse Peretz, who has been trying to find another project to work on with Rudd since The Château, says he never imagined anyone else in the role. “I knew that Paul would really find the sweetness in this guy and really get it. At the end of the day, the script is really leaning on someone taking this guy’s idealism and making you really root for it, and root for him,” he says, noting that once Rudd was onboard, casting the rest of the movie (Steve Coogan also stars) was easy: “Paul is a magnet for other actors, so after he said yes we just went to all the people we wanted and they said yes, too.”

RUDD IS NOW ONE OF THE MOST IN-DEMAND ACTORS WORKING TODAY. He just wrapped filming his part as Bill in The Perks of Being a Wallflower (Stephen Chbosky, who adapted the film from his own cult novel, sent Rudd the script with a note personally asking him to be in it), and stars in director David Wain’s Wanderlust alongside Jennifer Aniston and Justin Theroux, out in October. I ask him what his parents have made of his success. “They’re very proud,” he says. He leaves a pause here, and we both listen to the music meandering across the park. “That pride never wavered,” he continues. “No one in my family did this, and I think the idea that I was actually on television was a novelty to them. But they would have been proud—I know this—whatever I had done. I remember I was back in Kansas City and I found a bunch of videotapes. They were organized, and there was one called ‘Paul’s Premiere Party.’ It was the very first time an episode of Sisters aired, and they had a huge party and invited all of their friends around to watch it. I couldn’t watch the tape really, because my dad had recently died and....” As he looks up, I notice Rudd’s eyes have filled with tears. I offer to change the subject. “No, it’s OK,” he says. “My dad is hilarious and he was wearing this tuxedo...it was really sweet...they cheered when my name came up on the credits....” Another, longer pause. He smiles, wiping his eyes, looking away. “Damn you! What have you done to me?”

Two weeks after his father passed away, Rudd hosted Saturday Night Live. At the end, when he was on stage with the cast and guests (including Beyoncé and Justin Timberlake), he stepped forward, grabbed the lapel of his jacket, and looked upward. “He had known I was going to [host] it, and he was so excited,” he says. “I was wearing his jacket from when he was in the Navy....it was all kind of a blur.”

You could interview hundreds of actors and not witness this kind of raw honesty. And, as Rudd gets himself together and we discuss his father’s love of history and ephemera (Rudd once bought him F.A.O. Schwartz’s actual invitation to the offical opening of the Brooklyn Bridge), it occurs to me that while he certainly deserves his reputation as “nice,” it is far from his most important quality. Rudd is real: it is the quality that informs his best work, and something he has managed, against all odds, to keep intact throughout two decades in an industry seemingly purpose-built to destroy it. Does he have any regrets?

“Yeah, there are some things I still never talk about, but I look at my mom—my mom has been so amazing in the wake of my dad’s death,” he says, running a hand through his long hair and leaning back against the bench which, by now, is warm to the touch. “She doesn’t live in denial, she keeps busy and allows herself to be sad but is very vocal about the fact you have to adapt or perish. We live, we keep going. When I have tough patches, they inform what I do, but I adopt that motto, adapt or perish, and I try to live by it. And as great as it may sound to live a life without regrets, I wonder if that’s really living a life. You can’t appreciate the good weather until you’ve been through a few shitty winters.”