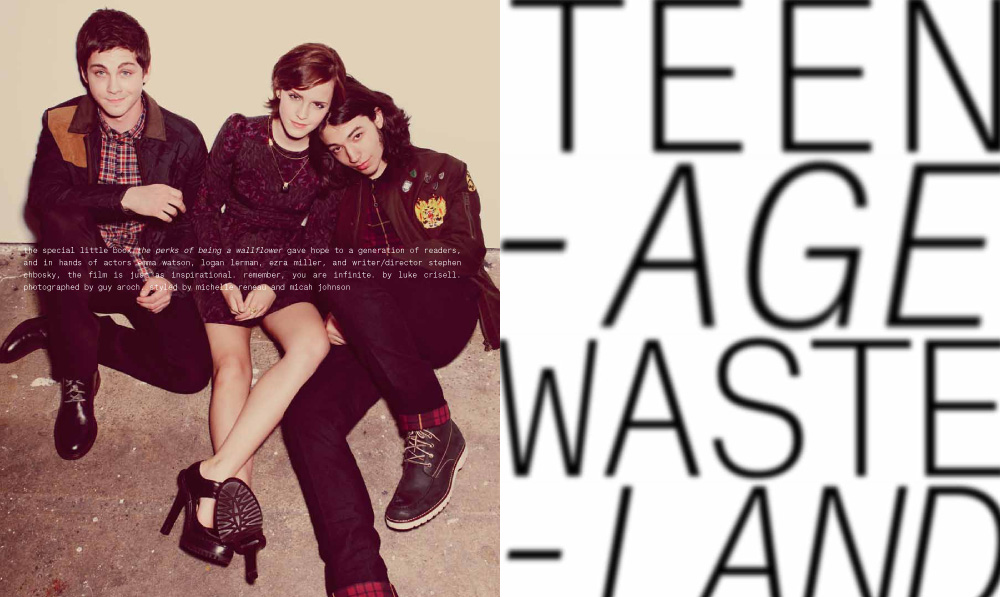

TEENAGE WASTELAND

The special little book the perks of being a wallflower gave hope to a generation of readers, and in hands of actors Emma Watson, Logan Lerman, Ezra Miller, and writer/director Stephen Chbosky, the film is just as inspirational. remember, you are infinite. By Luke Crisell.

“Every time I see this one particular movie star on a magazine, I can’t help but feel terribly sorry for her...the interviews all say the same thing. They start with what food they are eating in some restaurant. ‘As gingerly munched her Chinese chicken salad, she spoke of love...’ I think it’s nice for stars to do interviews to make us think they are just like us, but to tell you the truth, I get the feeling that it’s all a big lie. The problem is I don’t know who’s lying. And I don’t know why these magazines sell as much as they do.”

From The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

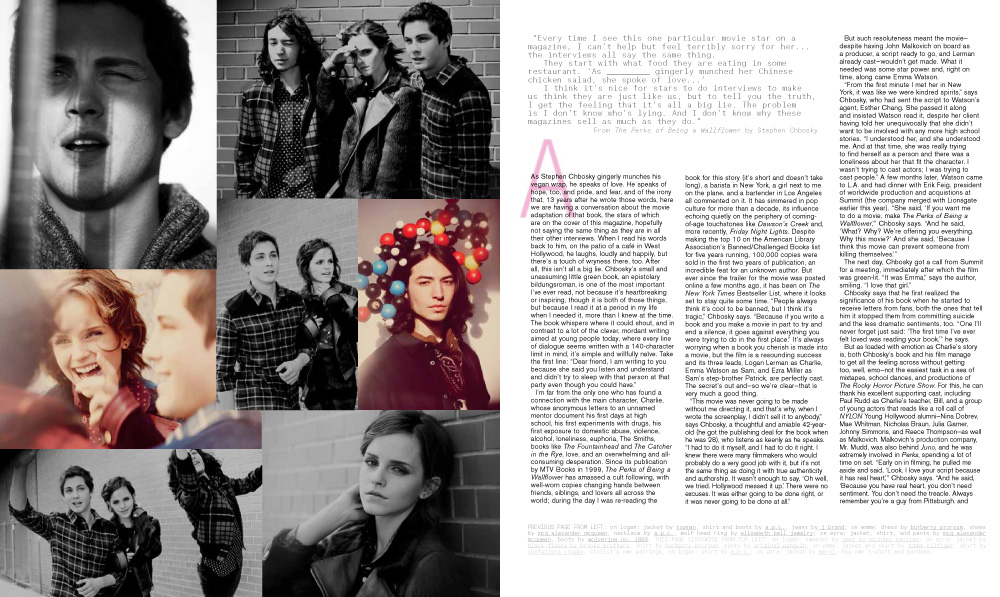

As Stephen Chbosky gingerly munches his vegan wrap, he speaks of love. He speaks of hope, too, and pride, and fear, and of the irony that, 13 years after he wrote those words, here we are having a conversation about the movie adaptation of that book, the stars of which are on the cover of this magazine, hopefully not saying the same thing as they are in all their other interviews. When I read his words back to him, on the patio of a café in West Hollywood, he laughs, loudly and happily, but there’s a touch of wryness there, too. After all, this isn’t all a big lie. Chbosky’s small and unassuming little green book, an epistolary bildungsroman, is one of the most important I’ve ever read, not because it’s heartbreaking or inspiring, though it is both of those things, but because I read it at a period in my life when I needed it, more than I knew at the time. The book whispers where it could shout, and in contrast to a lot of the clever, mordant writing aimed at young people today, where every line of dialogue seems written with a 140-character limit in mind, it’s simple and willfully naïve. Take the first line: “Dear friend, I am writing to you because she said you listen and understand and didn’t try to sleep with that person at that party even though you could have.”

I’m far from the only one who has found a connection with the main character, Charlie, whose anonymous letters to an unnamed mentor document his first days at high school, his first experiments with drugs, his first exposure to domestic abuse, violence, alcohol, loneliness, euphoria, The Smiths, books like The Fountainhead and The Catcher in the Rye, love, and an overwhelming and all-consuming desperation. Since its publication by MTV Books in 1999, The Perks of Being a Wallflower has amassed a cult following, with well-worn copies changing hands between friends, siblings, and lovers all across the world; during the day I was re-reading the book for this story (it’s short and doesn’t take long), a barista in New York, a girl next to me on the plane, and a bartender in Los Angeles all commented on it. It has simmered in pop culture for more than a decade, its influence echoing quietly on the periphery of coming-of-age touchstones like Dawson’s Creek and, more recently, Friday Night Lights. Despite making the top 10 on the American Library Association’s Banned/Challenged Books list for five years running, 100,000 copies were sold in the first two years of publication, an incredible feat for an unknown author. But ever since the trailer for the movie was posted online a few months ago, it has been on The New York Times Bestseller List, where it looks set to stay quite some time. “People always think it’s cool to be banned, but I think it’s tragic,” Chbosky says. “Because if you write a book and you make a movie in part to try and end a silence, it goes against everything you were trying to do in the first place.” It’s always worrying when a book you cherish is made into a movie, but the film is a resounding success and its three leads, Logan Lerman as Charlie, Emma Watson as Sam, and Ezra Miller as Sam’s step-brother Patrick, are perfectly cast. The secret’s out and—so we’re clear—that is very much a good thing.

“This movie was never going to be made without me directing it, and that’s why, when I wrote the screenplay, I didn’t sell it to anybody,” says Chbosky, a thoughtful and amiable 42-year- old (he got the publishing deal for the book when he was 28), who listens as keenly as he speaks. “I had to do it myself, and I had to do it right. I knew there were many filmmakers who would probably do a very good job with it, but it’s not the same thing as doing it with true authenticity and authorship. It wasn’t enough to say, ‘Oh well, we tried. Hollywood messed it up.’ There were no excuses. It was either going to be done right, or it was never going to be done at all.”

But such resoluteness meant the movie— despite having John Malkovich on board as a producer, a script ready to go, and Lerman already cast—wouldn’t get made. What it needed was some star power and, right on time, along came Emma Watson.

“From the first minute I met her in New York, it was like we were kindred spirits,” says Chbosky, who had sent the script to Watson’s agent, Esther Chang. She passed it along and insisted Watson read it, despite her client having told her unequivocally that she didn’t want to be involved with any more high school stories. “I understood her, and she understood me. And at that time, she was really trying to find herself as a person and there was a loneliness about her that fit the character. I wasn’t trying to cast actors; I was trying to cast people.” A few months later, Watson came to L.A. and had dinner with Erik Feig, president of worldwide production and acquistions at Summit (the company merged with Lionsgate earlier this year). “She said, ‘If you want me to do a movie, make The Perks of Being a Wallflower,’” Chbosky says. “And he said, ‘What? Why? We’re offering you everything. Why this movie?’ And she said, ‘Because I think this movie can prevent someone from killing themselves.’”

The next day, Chbosky got a call from Summit for a meeting, immediately after which the film was green-lit. “It was Emma,” says the author, smiling. “I love that girl.”

Chbosky says that he first realized the significance of his book when he started to receive letters from fans, both the ones that tell him it stopped them from committing suicide and the less dramatic sentiments, too. “One I’ll never forget just said: ‘The first time I’ve ever felt loved was reading your book,’” he says.

But as loaded with emotion as Charlie’s story is, both Chbosky’s book and his film manage to get all the feeling across without getting too, well, emo—not the easiest task in a sea of mixtapes, school dances, and productions of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. For this, he can thank his excellent supporting cast, including Paul Rudd as Charlie’s teacher, Bill, and a group of young actors that reads like a roll call of NYLON Young Hollywood alumni—Nina Dobrev, Mae Whitman, Nicholas Braun, Julia Garner, Johnny Simmons, and Reece Thompson—as well as Malkovich. Malkovich’s production company, Mr. Mudd, was also behind Juno, and he was extremely involved in Perks, spending a lot of time on set. “Early on in filming, he pulled me aside and said, ‘Look, I love your script because it has real heart,’” Chbosky says. “And he said, ‘Because you have real heart, you don’t need sentiment. You don’t need the treacle. Always remember you’re a guy from Pittsburgh. And always get the tough take.’” Chbosky’s actors bring this strength to his work, and also a vulnerability and humor that lend his words new dimensions. “Once I got the three of them on set, I knew: This was why I waited,” he says. “I truly believe, and I said this to all the cast, and I said this to all the crew: We will save lives here. Literally. This isn’t sentimental bullshit. It’s actual fact.”

Some of the defining scenes of the book (and now the film) see the three characters driving fast in a pickup truck through the Fort Pitt Tunnel in Pittsburgh, listening to music so loudly that everything becomes a blur of color, sound, and wind. Before filming in Pittsburgh began, Chbosky took his three lead actors there, put “Happiness” by Riceboy Sleeps on the stereo (as we’re talking, he plays it on his iPhone), and drove them through. “When we got out, I looked back and Emma was crying and Ezra had the biggest smile on his face,” he says. “Even Logan got choked up, and he never gets choked up. But I don’t know if they understood it until that moment. Like, this was me. We just went through the Fort Pitt Tunnel the way I did when I was a fucked-up kid at 16, driving through this thing over and over and over and dreaming about a better time and that, someday, I would go on and do something.”

EMMA WATSON

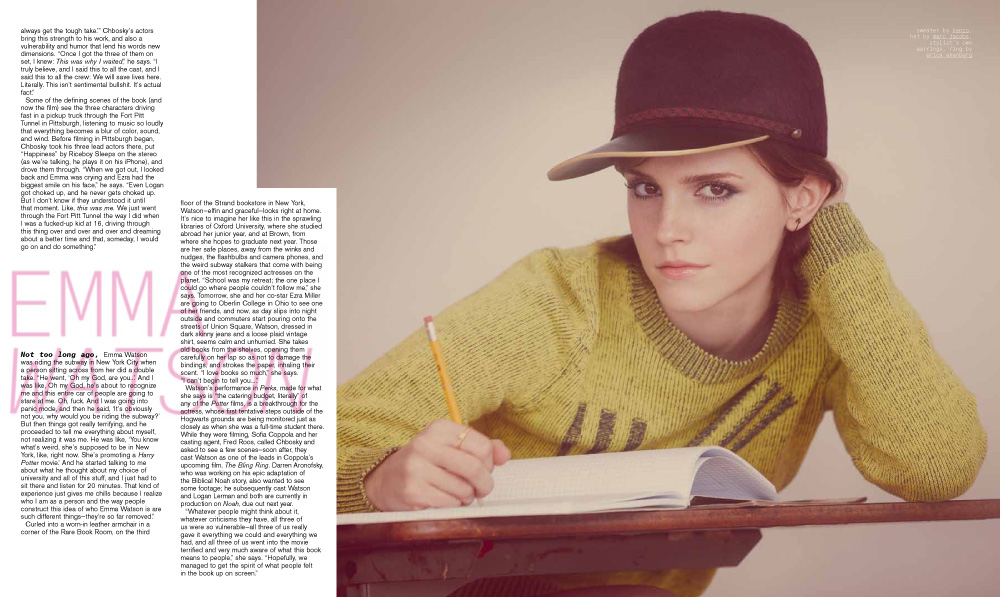

Not too long ago, Emma Watson was riding the subway in New York City when a person sitting across from her did a double take. “He went, ‘Oh my God, are you...’ And I was like, Oh my God, he’s about to recognize me and this entire car of people are going to stare at me. Oh, fuck. And I was going into panic mode, and then he said, ‘It’s obviously not you, why would you be riding the subway?’ But then things got really terrifying, and he proceeded to tell me everything about myself, not realizing it was me. He was like, ‘You know what’s weird, she’s supposed to be in New York, like, right now. She’s promoting a Harry Potter movie.’ And he started talking to me about what he thought about my choice of university and all of this stuff, and I just had to sit there and listen for 20 minutes. That kind of experience just gives me chills because I realize who I am as a person and the way people construct this idea of who Emma Watson is are such different things—they’re so far removed.”

Curled into a worn-in leather armchair in a corner of the Rare Book Room, on the third floor of the Strand bookstore in New York, Watson—elfin and graceful—looks right at home. It’s nice to imagine her like this in the sprawling libraries of Oxford University, where she studied abroad her junior year, and at Brown, from where she hopes to graduate next year. Those are her safe places, away from the winks and nudges, the flashbulbs and camera phones, and the weird subway stalkers that come with being one of the most recognized actresses on the planet. “School was my retreat; the one place I could go where people couldn’t follow me,” she says. Tomorrow, she and her co-star Ezra Miller are going to Oberlin College in Ohio to see one of her friends, and now, as day slips into night outside and commuters start pouring onto the streets of Union Square, Watson, dressed in dark skinny jeans and a loose plaid vintage shirt, seems calm and unhurried. She takes old books from the shelves, opening them carefully on her lap so as not to damage the bindings, and strokes the paper, inhaling their scent. “I love books so much,” she says. “I can’t begin to tell you....”

Watson’s performance in Perks, made for what she says is “the catering budget, literally” of any of the Potter films, is a breakthrough for the actress, whose first tentative steps outside of the Hogwarts grounds are being monitored just as closely as when she was a full-time student there. While they were filming, Sofia Coppola and her casting agent, Fred Roos, called Chbosky and asked to see a few scenes—soon after, they cast Watson as one of the leads in Coppola’s upcoming film, The Bling Ring. Darren Aronofsky, who was working on his epic adaptation of the Biblical Noah story, also wanted to see some footage; he subsequently cast Watson and Logan Lerman and both are currently in production on Noah, due out next year.

“Whatever people might think about it, whatever criticisms they have, all three of us were so vulnerable—all three of us really gave it everything we could and everything we had, and all three of us went into the movie terrified and very much aware of what this book means to people,” she says. “Hopefully, we managed to get the spirit of what people felt in the book up on screen.”

In fact, Watson only decided she actually wanted to pursue acting as a career after she wrapped Perks, about a year ago. She fell into the Harry Potter franchise as a nine-year- old after a casting agent visited her school in Oxfordshire, England, and spent the next 10 years playing the precocious Hermione Granger in eight of the most successful films in the history of cinema. “I’ve done my life backwards; it’s really bizarre,” she says. “Most of my friends are just about to start working, and I’ve had a job for the past 10 years. It’s strange, because most people spend that decade figuring themselves out and figuring out what they like and what they don’t like—just making mistakes in the privacy of their own teenage bedrooms. And I am kind of doing everything in a different way, so sometimes it’s a bit isolating....” She trails off and looks around the room, then at the recorder on the arm of her chair as if she wishes it weren’t there, just this once. “I’m in a slightly different place.”

Perks was a good project for the adult Emma Watson, now 22, who up until then had thought she might try journalism as a career, to start with. “I feel more directly creatively involved with the whole project—you’re part of a very small, passionate group of people who are trying to bring something to life,” she says. “You feel like you’re in a traveling circus, or a company of actors.”

Now, in addition to The Bling Ring and Noah, she is about to start filming Your Voice in My Head, in which she will play Emma Forrest, the writer of the memoir the film is based on, who’s struggling with manic depression, and she’s attached to Guillermo del Toro’s Beauty and the Beast. It’s hard to imagine a more exciting pairing of fairytale and director and, as it turns out, we have Watson to thank for that, too: “The script came to me, and it was a little bit cheesy and kooky, and I was like, ‘I don’t really want to do this,’” she says, warily eyeing a thirtysomething guy who has been loitering for a suspiciously long time not too far away. “I said the only reason I would do it would be if someone like Guillermo del Toro did it, and Greg Silverman, who’s the head of Warner Brothers, said to me, ‘Well, why don’t you email him?’ So I did, and he emailed back, saying, ‘Beauty is my favorite fairytale. It’s a story I’ve always wanted to tell. I can’t let anybody else do this project, and I think you’re perfect for it.’ And we started talking, having these three-hour conversations, and he’s starting to build the world.”

Because the loitering guy seems intent on pretending to study a shelf of old medical books too close to us for comfort, we walk over to the other side of the room, to some stacks of poetry, scanning the faded spines for familiar names. “I never wanted any of the things that a lot of the people who go into this industry want,” Watson says. “I never wanted to be famous. My parents never wanted this for me. I never even wanted this until a year ago. I was so overwhelmed by the way that people responded to the idea that this might not be what I want to do [something Watson said publicly while promoting the seventh Harry Potter film], but I hope people will respect my choice more now that I really took time to consider it, and what it really means. Now that I’ve made my decision, I’m serious about mastering my craft and really doing things that I genuinely believe are important.” She sighs quietly. “I think the line between what being an actor is and what being a celebrity is has gotten so fuzzy that people don’t even know what we do anymore. Models are actresses and actresses are models and actresses are designing sofas, and it’s crazy. I don’t know if it will change, but I’m going to try to do this the right way.”

LOGAN LERMAN

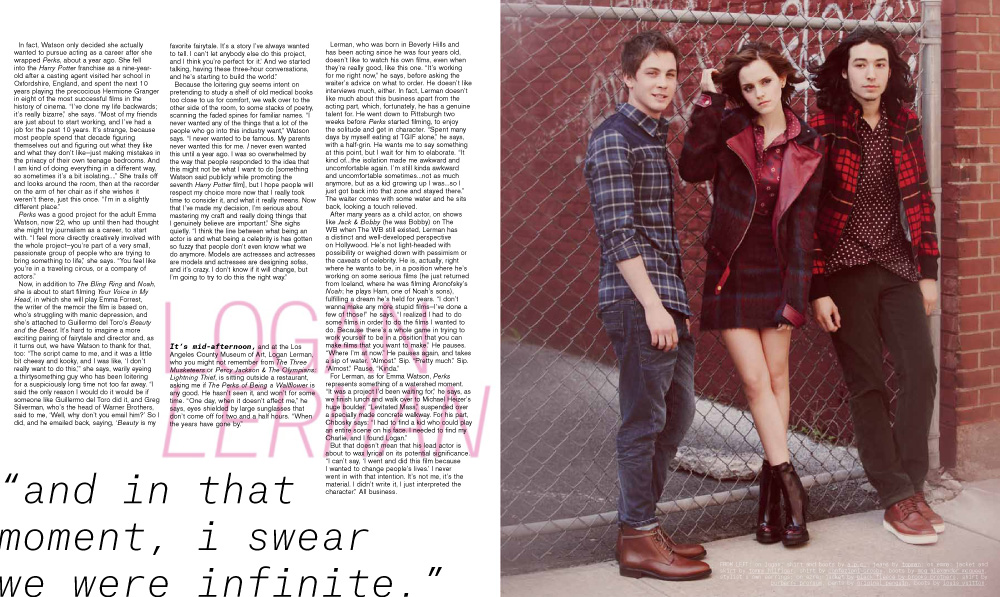

It’s mid-afternoon, and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Logan Lerman, who you might not remember from The Three Musketeers or Percy Jackson & The Olympians: Lightning Thief, is sitting outside a restaurant, asking me if The Perks of Being a Wallflower is any good. He hasn’t seen it, and won’t for some time. “One day, when it doesn’t affect me,” he says, eyes shielded by large sunglasses that don’t come off for two and a half hours. “When the years have gone by.”

Lerman, who was born in Beverly Hills and has been acting since he was four years old, doesn’t like to watch his own films, even when they’re really good, like this one. “It’s working for me right now,” he says, before asking the waiter’s advice on what to order. He doesn’t like interviews much, either. In fact, Lerman doesn’t like much about this business apart from the acting part, which, fortunately, he has a genuine talent for. He went down to Pittsburgh two weeks before Perks started filming, to enjoy the solitude and get in character. “Spent many days by myself eating at TGIF alone,” he says, with a half-grin. He wants me to say something at this point, but I wait for him to elaborate. “It kind of...the isolation made me awkward and uncomfortable again. I’m still kinda awkward and uncomfortable sometimes...not as much anymore, but as a kid growing up I was...so I just got back into that zone and stayed there.” The waiter comes with some water and he sits back, looking a touch relieved.

After many years as a child actor, on shows like Jack & Bobby (he was Bobby) on The WB when The WB still existed, Lerman has a distinct and well-developed perspective on Hollywood. He’s not light-headed with possibility or weighed down with pessimism or the caveats of celebrity. He is, actually, right where he wants to be, in a position where he’s working on some serious films (he just returned from Iceland, where he was filming Aronofsky’s Noah; he plays Ham, one of Noah’s sons), fulfilling a dream he’s held for years. “I don’t wanna make any more stupid films—I’ve done a few of those!” he says. “I realized I had to do some films in order to do the films I wanted to do. Because there’s a whole game in trying to work yourself to be in a position that you can make films that you want to make.” He pauses. “Where I’m at now.” He pauses again, and takes a sip of water. “Almost.” Sip. “Pretty much.” Sip. “Almost.” Pause. “Kinda.”

For Lerman, as for Emma Watson, Perks represents something of a watershed moment. “It was a project I’d been waiting for,” he says, as we finish lunch and walk over to Michael Heizer’s huge boulder, “Levitated Mass,” suspended over a specially made concrete walkway. For his part, Chbosky says: “I had to find a kid who could play an entire scene on his face. I needed to find my Charlie, and I found Logan.”

But that doesn’t mean that his lead actor is about to wax lyrical on its potential significance. “I can’t say, ‘I went and did this film because I wanted to change people’s lives.’ I never went in with that intention. It’s not me, it’s the material. I didn’t write it, I just interpreted the character.” All business.

But Lerman has good reason to keep his eye on the ball. His entire career, he’s watched actors come and go, crash and burn, never make it past a Gap commercial. “I dipped my toes in the Valley actor world and I noticed it’s a pretty sad and desperate place,” he says as we walk underneath the monolith. “These families had moved their entire lives, and a seven-year- old is paying for their mom’s apartment, and their only interest is to get on a Disney show and become the next Lizzie McGuire or some shit like that. Their only interest is to make money and become famous.”

Lerman though, is taking things at his own pace. His experiences as a child actor have tempered his interest in publicity of any form, including stuff like this, and who can blame him? “Growing up, nothing was genuine in the publicity side of making a movie,” he says.

“It was putting this kid, me, in this room, dressed the way they want me to be dressed, saying the things they’d prepped me to say, and it was so artificial. I hated it. It’s such fake bullshit. It would make me depressed.” We head back to a courtyard to find a table. “I don’t need to look for validation,” he says as he pulls out a metal chair.

Before he starts filming any role, Lerman writes some music for the character. Chbosky played me the piece Lerman wrote for Charlie on his iPhone, a gentle lament on piano that was remarkable for just how not-in-any-way-embarrassing it was. It was pretty amazing, as it happens. “It’s just therapeutic,” he says. “It just helps me.” One of his dreams, he says, would be to play live on stage. “I want to have a band; that would be so cool,” he says. “But I find that so, ‘Meh, another fucking actor playing music.’”

I ask why he doesn’t just go for it. He’s clearly got musical talent; that much is obvious on the basis of one solo piano piece. And something about Lerman just makes you want the best for the guy. “Yeah!” he says, more confidently. He hits his fist on the table, not hard, but symbolically. “I totally will.” He looks over at some kids playing in a sculpture made from yellow plastic ropes then says it again: “You know, I totally will.”

EZRA MILLER

I’ve been waiting outside Ezra Miller’s apartment in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood for half an hour when my phone rings. “I’m so sorry, but I’m miles away,” says Miller, calling from the back of a car somewhere in Queens. “I know we need to meet, though, and I want to do this right.” After talking for a while, it transpires we are both going to be in Los Angeles later that day. “So let’s meet up there?” Miller suggests. “Get fucked up in the City of Angels!”

Ezra Miller, born in New Jersey in 1992 to a modern dancer mother and a publisher father, is a singular human being. The actor, who is best known for his lightning-strike of a role in last year’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, speaks in overly complicated, verbose sentences that often have a sort of crazy, fever-dream poetry to them. He’s grandiose and prone to gesticulations that require the use of his entire body, but beneath all the 10-dollar words and theatricality, there’s a sincerity and honesty to a lot of what he says that you just don’t find with most 20-year-old actors. His work betrays this uniqueness, and as Patrick, Charlie’s gay friend who looks after him and shows him that not everyone has to fit in, he electrifies Perks. “He was just so alive, and I knew that his free energy would help [Watson and Lerman],” says Chbosky, whose wife pointed out that Miller would be a good Patrick when they were watching the 2009 film City Island together.

The following afternoon, Miller texts me to meet him at a pizzeria on a run-down block of Sunset Boulevard, wedged between dollar stores and windowless medical marijuana joints. When I arrive, it turns out that an episode of the show Parenthood is being filmed in the restaurant—Miller is friends with two of the stars, Sarah Ramos and Mae Whitman, and when I finally get inside, I find a lot more young actors gathered in a corner, waiting for the shoot to wrap so they can all hang out. Johnny Simmons has just come from an audition, Alia Shawkat is sitting on a crate, Miles Teller is there, and many more. I’ve met most of them before on NYLON shoots, and after some catching up, I ask if they’ve seen Miller around. “Ezra’s here!?” Shawkat says, quickly being shushed by some grips. She whispers: “Are you serious?”

“Ezra?!” asks Whitman, excitedly. “Johnny, did you know Ezra was here?”

He didn’t. No one else seems to, either. Then, around the corner strides Miller, wearing cropped drawstring cotton pants that were once white and an off-white net tank top that has been paid the same amount of laundering attention, with large tribal-style necklaces swinging around his neck, his hair shoulder length and all over the place. He enters the room looking like a kind of disheveled, bohemian Jesus, greeting his disciples with arms outstretched, administering hugs and high fives in equal measure.

“I recognize this industry and this job and this lifestyle are all really fun, and there’s a really nice comfortable world out here for the exclusive club of people who get to be involved,” he says a little later, outside a miserable Burger King drive-thru down the street. I’m sitting on a wall and had assumed he’d sit next to me, but he never does—he paces, twirls, and moves constantly, when he moves too far away, he spins back closer, like one of those battery-powered puppies in a toy store. “I look at a lot of my friends in this industry, and they’re not doing what they want to do, which is sad and sucky ’cause they’re amazing artists who should be doing the art they wanna do,” he says. “I’m always feeling unsatisfied, like I haven’t done shit yet, like I’ve gotta find the project that’s going to change the whole fucking game.” He takes a swig from his bottle of Mexican soda, which he has been holding in such a way that I half expect him to chuck it at a passing car.

“The fact is, I have an insatiable need to make art that will, at the very least, change my life. And in the hopeful extreme, change the life and perspective of any motherfucker that comes in contact with it,” he says, taking a deep drag on the cigarette that is perpetually between his lips, facing away from me, looking down Sunset toward a sea of cheap billboards competing for attention.

But why acting? I ask. Why aren’t you an interpretive dancer or a poet or something? He turns to stare at me, pushing his long hair out of his eyes, and doesn’t miss a beat: “I am, and I am. It’s a shame that once you do an art form for a while, people associate you with that art form. I plan to do battle with that particular notion over the course of my life. There are so many things I wanna do. So many interpretive dances I wanna make.”

Unlike Lerman or Watson, who read the book for the job, Perks has had a special place in Miller’s heart for years. “I felt like I had certain pieces of art that were almost body armor,” he says, so astutely that I wish I’d come up with the phrase myself. “It was the only protection or salvation available—these few films, few books, few albums—and Perks was very much one of them. When I heard they were making it into a movie...I was like, ‘What the fuck is going on?!’ Sign of the apocalypse number 104,436! That just can’t go right. But it was sent to me and it said ‘Written and directed by Stephen Chboksy,’ and it was like a switch flipped when I read that.”

Although he’s only 20, Miller has come to the realization that, while Hollywood might not be the best place for him, he’s going to try it out anyway. “Humans always know the story,” he says. “This is Shakespeare shit: Romeo’s going into the party and he can just feel it, and he says: ‘I’m about to meet some path that’s going to kill me’ [“Some consequence, yet hanging in the stars/ Shall bitterly begin his fearful date/ With this night’s revels,” Act I, Scene IV]. When you meet that girl, you’re like, ‘You’re going to break my heart.’ But I’ve come to that place with my job. This industry, and the storytelling machine that’s out here in Los Angeles fucks people up. Really, like, ruins kids and shit, you know? It’s everybody’s fault, because even if you’re not out here supplying the stories, you’re somewhere else demanding them.” He drains his soda and lights another cigarette, inhaling deeply. “I guess I’m just down to get fucked up.”