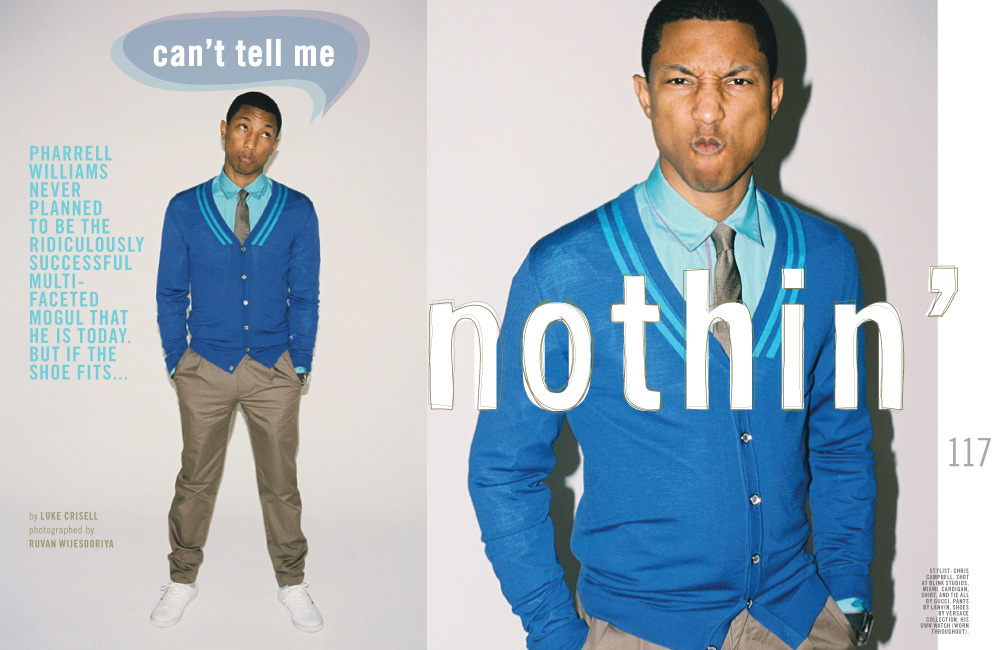

CAN’T TELL ME NOTHIN’

PHARRELL WILLIAMS NEVER PLANNED TO BE THE RIDICULOUSLY SUCCESSFUL MULTIFACETED MOGUL THAT HE IS TODAY. BUT IF THE SHOE FITS...

THERE’S SOMETHING EVER-SO-SLIGHTLY SAD about Miami Beach. The glamour of the city’s famed Art Deco District, despite a recent flurry of developments, is largely forgotten today. The confectionary-colored buildings, most of them hotels, stand as faded, incongruous monuments to a wide-eyed time of fantasy and speculation: a fleeting moment long ago, which will probably never be again. Collins Avenue dissects this curious little municipality, and visitors here stream along it, many of them agitated with that fraught resort mentality which places the pursuit of fun above all else. On one of the street’s less salubrious corners two of these tourists pose in front of a Mercedes SLR McLaren—a $500,000 supercar that looks like it hasn’t been washed in a month.

“Oh, my God! You never see these!” says the guy, who is wearing a Hawaiian shirt and cargo shorts. “Only famous people have them.”

“Ooh,” says the girl, her sundress whipping in the wind. “I wonder who owns this one.” She turns and looks at the rundown, seafoam-green structure behind her. “Do you think they’re in there?”

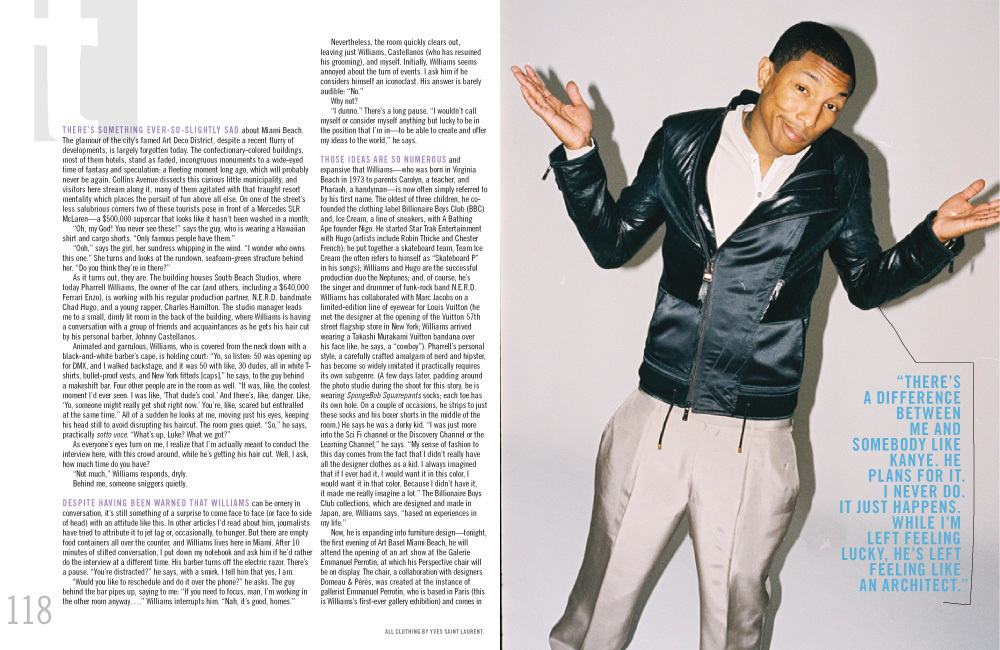

As it turns out, they are. The building houses South Beach Studios, where today Pharrell Williams, the owner of the car (and others, including a $640,000 Ferrari Enzo), is working with his regular production partner, N.E.R.D. bandmate Chad Hugo, and a young rapper, Charles Hamilton. The studio manager leads me to a small, dimly lit room in the back of the building, where Williams is having a conversation with a group of friends and acquaintances as he gets his hair cut by his personal barber, Johnny Castellanos.

Animated and garrulous, Williams, who is covered from the neck down with a black-and-white barber’s cape, is holding court: “Yo, so listen: 50 was opening up for DMX, and I walked backstage, and it was 50 with like, 30 dudes, all in white T- shirts, bullet-proof vests, and New York fitteds [caps],” he says, to the guy behind a makeshift bar. Four other people are in the room as well. “It was, like, the coolest moment I’d ever seen. I was like, ‘That dude’s cool.’ And there’s, like, danger. Like, ‘Yo, someone might really get shot right now.’ You’re, like, scared but enthralled at the same time.” All of a sudden he looks at me, moving just his eyes, keeping his head still to avoid disrupting his haircut. The room goes quiet. “So,” he says, practically sotto voce. “What’s up, Luke? What we got?”

As everyone’s eyes turn on me, I realize that I’m actually meant to conduct the interview here, with this crowd around, while he’s getting his hair cut. Well, I ask, how much time do you have?

“Not much,” Williams responds, dryly. Behind me, someone sniggers quietly.

DESPITE HAVING BEEN WARNED THAT WILLIAMS can be ornery in conversation, it’s still something of a surprise to come face to face (or face to side of head) with an attitude like this. In other articles I’d read about him, journalists have tried to attribute it to jet lag or, occasionally, to hunger. But there are empty food containers all over the counter, and Williams lives here in Miami. After 10 minutes of stilted conversation, I put down my notebook and ask him if he’d rather do the interview at a different time. His barber turns off the electric razor. There’s a pause. “You’re distracted?” he says, with a smirk. I tell him that yes, I am.

“Would you like to reschedule and do it over the phone?” behind the bar pipes up, saying to me: “If you need to focus, man, I’m working in the other room anyway....” Williams interrupts him. “Nah, it’s good, homes.”

Nevertheless, the room quickly clears out, leaving just Williams, Castellanos (who has resumed his grooming), and myself. Initially, Williams seems annoyed about the turn of events. I ask him if he considers himself an iconoclast. His answer is barely audible: “No.”

Why not?

“I dunno.” There’s a long pause. “I wouldn’t call myself or consider myself anything but lucky to be in the position that I’m in—to be able to create and offer my ideas to the world,” he says.

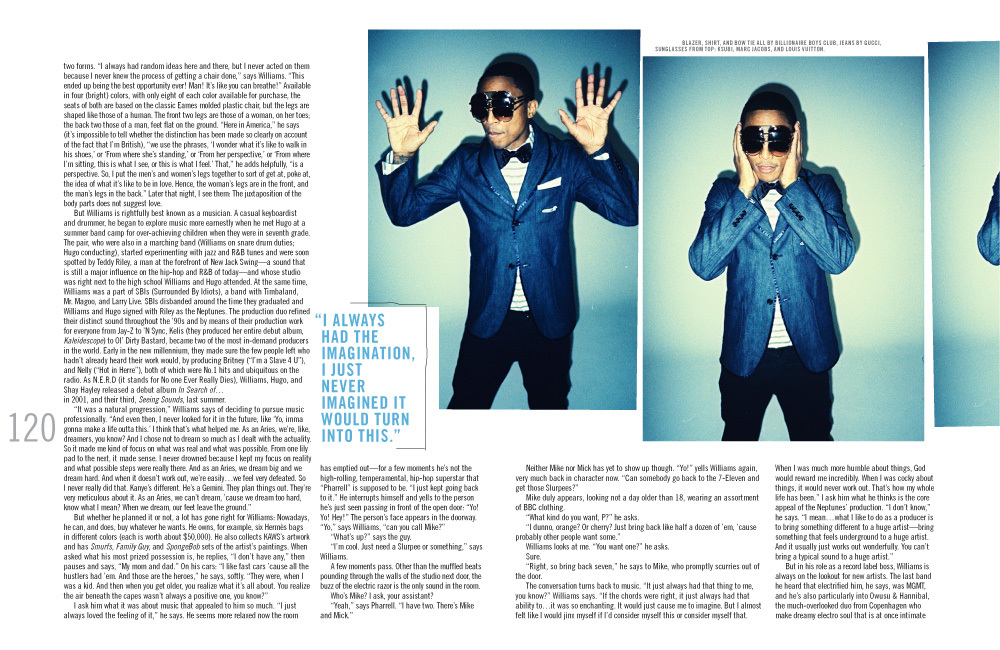

THOSE IDEAS ARE SO NUMEROUS and expansive that Williams—who was born in Virginia Beach in 1973 to parents Carolyn, a teacher, and Pharaoh, a handyman—is now often simply referred to by his first name. The oldest of three children, he co- founded the clothing label Billionaire Boys Club (BBC) and, Ice Cream, a line of sneakers, with A Bathing Ape founder Nigo. He started Star Trak Entertainment with Hugo (artists include Robin Thicke and Chester French); he put together a skateboard team, Team Ice Cream (he often refers to himself as “Skateboard P” in his songs); Williams and Hugo are the successful production duo the Neptunes; and, of course, he’s the singer and drummer of funk-rock band N.E.R.D. Williams has collaborated with Marc Jacobs on a limited-edition line of eyewear for Louis Vuitton (he met the designer at the opening of the Vuitton 57th street flagship store in New York; Williams arrived wearing a Takashi Murakami Vuitton bandana over his face like, he says, a “cowboy”). Pharrell’s personal style, a carefully crafted amalgam of nerd and hipster, has become so widely imitated it practically requires its own sub-genre. (A few days later, padding around the photo studio during the shoot for this story, he is wearing SpongeBob Squarepants socks; each toe has its own hole. On a couple of occasions, he strips to just these socks and his boxer shorts in the middle of the room.) He says he was a dorky kid. “I was just more into the Sci Fi channel or the Discovery Channel or the Learning Channel,” he says. “My sense of fashion to this day comes from the fact that I didn’t really have all the designer clothes as a kid. I always imagined that if I ever had it, I would want it in this color, I would want it in that color. Because I didn’t have it, it made me really imagine a lot.” The Billionaire Boys Club collections, which are designed and made in Japan, are, Williams says, “based on experiences in my life.”

Now, he is expanding into furniture design—tonight, the first evening of Art Basel Miami Beach, he will attend the opening of an art show at the Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, at which his Perspective chair will be on display. The chair, a collaboration with designers Domeau & Pérès, was created at the instance of gallerist Emmanuel Perrotin, who is based in Paris (this is Williams’s first-ever gallery exhibition) and comes in two forms. “I always had random ideas here and there, but I never acted on them because I never knew the process of getting a chair done,” says Williams. “This ended up being the best opportunity ever! Man! It’s like you can breathe!” Available in four (bright) colors, with only eight of each color available for purchase, the seats of both are based on the classic Eames molded plastic chair, but the legs are shaped like those of a human. The front two legs are those of a woman, on her toes; the back two those of a man, feet flat on the ground. “Here in America,” he says (it’s impossible to tell whether the distinction has been made so clearly on account of the fact that I’m British), “we use the phrases, ‘I wonder what it’s like to walk in his shoes,’ or ‘From where she’s standing,’ or ‘From her perspective,’ or ‘From where I’m sitting, this is what I see, or this is what I feel.’ That,” he adds helpfully, “is a perspective. So, I put the men’s and women’s legs together to sort of get at, poke at, the idea of what it’s like to be in love. Hence, the woman’s legs are in the front, and the man’s legs in the back.” Later that night, I see them: The juxtaposition of the body parts does not suggest love.

But Williams is rightfully best known as a musician. A casual keyboardist and drummer, he began to explore music more earnestly when he met Hugo at a summer band camp for over-achieving children when they were in seventh grade. The pair, who were also in a marching band (Williams on snare drum duties; Hugo conducting), started experimenting with jazz and R&B tunes and were soon spotted by Teddy Riley, a man at the forefront of New Jack Swing—a sound that is still a major influence on the hip-hop and R&B of today—and whose studio was right next to the high school Williams and Hugo attended. At the same time, Williams was a part of SBIs (Surrounded By Idiots), a band with Timbaland, Mr. Magoo, and Larry Live. SBIs disbanded around the time they graduated and Williams and Hugo signed with Riley as the Neptunes. The production duo refined their distinct sound throughout the ’90s and by means of their production work for everyone from Jay-Z to ’N Sync, Kelis (they produced her entire debut album, Kaleidescope) to Ol’ Dirty Bastard, became two of the most in-demand producers in the world. Early in the new millennium, they made sure the few people left who hadn’t already heard their work would, by producing Britney (“I’m a Slave 4 U”), and Nelly (“Hot in Herre”), both of which were No.1 hits and ubiquitous on the radio. As N.E.R.D (it stands for No one Ever Really Dies), Williams, Hugo, and Shay Hayley released a debut album In Search of… in 2001, and their third, Seeing Sounds, last summer.

“It was a natural progression,” Williams says of deciding to pursue music professionally. “And even then, I never looked for it in the future, like ‘Yo, imma gonna make a life outta this.’ I think that’s what helped me. As an Aries, we’re, like, dreamers, you know? And I chose not to dream so much as I dealt with the actuality. So it made me kind of focus on what was real and what was possible. From one lily pad to the next, it made sense. I never drowned because I kept my focus on reality and what possible steps were really there. And as an Aries, we dream big and we dream hard. And when it doesn’t work out, we’re easily…we feel very defeated. So I never really did that. Kanye’s different. He’s a Gemini. They plan things out. They’re very meticulous about it. As an Aries, we can’t dream, ’cause we dream too hard, know what I mean? When we dream, our feet leave the ground.”

But whether he planned it or not, a lot has gone right for Williams: Nowadays, he can, and does, buy whatever he wants. He owns, for example, six Hermès bags in different colors (each is worth about $50,000). He also collects KAWS’s artwork and has Smurfs, Family Guy, and SpongeBob sets of the artist’s paintings. When asked what his most prized possession is, he replies, “I don’t have any,” then pauses and says, “My mom and dad.” On his cars: “I like fast cars ’cause all the hustlers had ’em. And those are the heroes,” he says, softly. “They were, when I was a kid. And then when you get older, you realize what it’s all about. You realize the air beneath the capes wasn’t always a positive one, you know?”

I ask him what it was about music that appealed to him so much. “I just always loved the feeling of it,” he says. He seems more relaxed now the room has emptied out—for a few moments he’s not the high-rolling, temperamental, hip-hop superstar that “Pharrell” is supposed to be. “I just kept going back to it.” He interrupts himself and yells to the person he’s just seen passing in front of the open door: “Yo! Yo! Hey!” The person’s face appears in the doorway. “Yo,” says Williams, “can you call Mike?”

“What’s up?” says the guy.

“I’m cool. Just need a Slurpee or something,” says Williams.

A few moments pass. Other than the muffled beats pounding through the walls of the studio next door, the buzz of the electric razor is the only sound in the room.

Who’s Mike? I ask, your assistant?

"Yeah,” says Pharrell. “I have two. There’s Mike and Mick.”

Neither Mike nor Mick has yet to show up though. “Yo!” yells Williams again, very much back in character now. “Can somebody go back to the 7-Eleven and get those Slurpees?”

Mike duly appears, looking not a day older than 18, wearing an assortment of BBC clothing.

“What kind do you want, P?” he asks.

“I dunno, orange? Or cherry? Just bring back like half a dozen of ’em, ’cause probably other people want some.”

Williams looks at me. “You want one?” he asks. Sure. “Right, so bring back seven,” he says to Mike, who promptly scurries out of the door. The conversation turns back to music. “It just always had that thing to me, you know?” Williams says. “If the chords were right, it just always had that ability to...it was so enchanting. It would just cause me to imagine. But I almost felt like I would jinx myself if I’d consider myself this or consider myself that. When I was much more humble about things, God would reward me incredibly. When I was cocky about things, it would never work out. That’s how my whole life has been.” I ask him what he thinks is the core appeal of the Neptunes’ production. “I don’t know,” he says. “I mean...what I like to do as a producer is to bring something different to a huge artist—bring something that feels underground to a huge artist. And it usually just works out wonderfully. You can’t bring a typical sound to a huge artist.”

But in his role as a record label boss, Williams is always on the lookout for new artists. The last band he heard that electrified him, he says, was MGMT, and he’s also particularly into Owusu & Hannibal, the much-overlooked duo from Copenhagen who make dreamy electro soul that is at once intimate and expansive; they are responsible for one of the best albums of 2006, Living with Owusu & Hannibal. I ask Williams if finding new talent is something that excites him. “I’m not really keen on signing people,” he replies. “I’m not. I’m not in record label mode these days.” Despite this, the reason Williams is in the studio today is to work with Charles Hamilton, one of the most promising young talents in rap. At one point, Hamilton, who is 21, from Harlem, and quite shy, walks in.

“Yeah! Nigga, the bitches is comin!’” yells Williams. “Yo, what was that shit you spit earlier?” Hamilton then starts freestyling, with jaw-dropping deftness.

“I mean, is he not stupid!?” says Williams. He looks back at Hamilton and shouts again: “Yeah, man!”

“He’s super-talented,” Williams continues, who seems energized by the exchange. “He’s a genius.”

“[We met at] the Four Seasons, right?” says Hamilton. “I had just taken a shower that day for the first time in a couple of days.”

“Yup,” says Williams.

“The Four Seasons, a glass of Baileys,” says

Hamilton. “Speakin’ of which, is that an unopened bottle of Baileys?”

“C’mon man, don’t go crazy,” says Williams, sounding concerned. “Stay focused.”

Williams turns to me. “By the way, this is one of like thousands, this kid. And he’s....” From the corner of his eye he notices Hamilton, who has the Baileys open, and is pouring himself a generous measure.

“All right! Easy, Charles!”

“C’mon, man!” says Hamilton, a little bit desperately. “There’s no alcohol in this shit. It’s all cream, man, I’m good.”

“I do like Baileys,” says Williams, “but you know.”

“I feel where you’re coming from man,” says Hamilton, taking a sip. “But I know my limit, I’m good.”

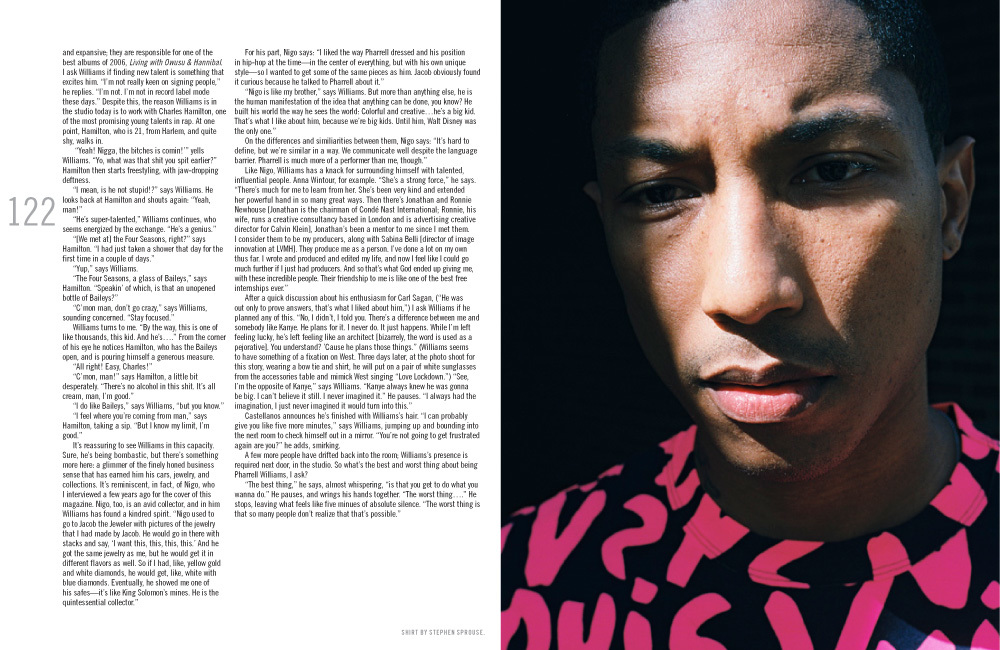

It’s reassuring to see Williams in this capacity. Sure, he’s being bombastic, but there’s something more here: a glimmer of the finely honed business sense that has earned him his cars, jewelry, and collections. It’s reminiscent, in fact, of Nigo, who I interviewed a few years ago for the cover of this magazine. Nigo, too, is an avid collector, and in him Williams has found a kindred spirit. “Nigo used to go to Jacob the Jeweler with pictures of the jewelry that I had made by Jacob. He would go in there with stacks and say, ‘I want this, this, this, this.’ And he got the same jewelry as me, but he would get it in different flavors as well. So if I had, like, yellow gold and white diamonds, he would get, like, white with blue diamonds. Eventually, he showed me one of his safes—it’s like King Solomon’s mines. He is the quintessential collector.”

For his part, Nigo says: “I liked the way Pharrell dressed and his position in hip-hop at the time—in the center of everything, but with his own unique style—so I wanted to get some of the same pieces as him. Jacob obviously found it curious because he talked to Pharrell about it.”

“Nigo is like my brother,” says Williams. But more than anything else, he is the human manifestation of the idea that anything can be done, you know? He built his world the way he sees the world: Colorful and creative...he’s a big kid. That’s what I like about him, because we’re big kids. Until him, Walt Disney was the only one.”

On the differences and similarities between them, Nigo says: “It’s hard to define, but we’re similar in a way. We communicate well despite the language barrier. Pharrell is much more of a performer than me, though.”

Like Nigo, Williams has a knack for surrounding himself with talented, influential people. Anna Wintour, for example. “She’s a strong force,” he says. “There’s much for me to learn from her. She’s been very kind and extended her powerful hand in so many great ways. Then there’s Jonathan and Ronnie Newhouse [Jonathan is the chairman of Condé Nast International; Ronnie, his wife, runs a creative consultancy based in London and is advertising creative director for Calvin Klein], Jonathan’s been a mentor to me since I met them. I consider them to be my producers, along with Sabina Belli [director of image innovation at LVMH]. They produce me as a person. I’ve done a lot on my own thus far. I wrote and produced and edited my life, and now I feel like I could go much further if I just had producers. And so that’s what God ended up giving me, with these incredible people. Their friendship to me is like one of the best free internships ever.”

After a quick discussion about his enthusiasm for Carl Sagan, (“He was out only to prove answers, that’s what I liked about him,”) I ask Williams if he planned any of this. “No, I didn’t, I told you. There’s a difference between me and somebody like Kanye. He plans for it. I never do. It just happens. While I’m left feeling lucky, he’s left feeling like an architect [bizarrely, the word is used as a pejorative]. You understand? ’Cause he plans those things.” (Williams seems to have something of a fixation on West. Three days later, at the photo shoot for this story, wearing a bow tie and shirt, he will put on a pair of white sunglasses from the accessories table and mimick West singing “Love Lockdown.”) “See, I’m the opposite of Kanye,” says Williams. “Kanye always knew he was gonna be big. I can’t believe it still. I never imagined it.” He pauses. “I always had the imagination, I just never imagined it would turn into this.”

Castellanos announces he’s finished with Williams’s hair. “I can probably give you like five more minutes,” says Williams, jumping up and bounding into the next room to check himself out in a mirror. “You’re not going to get frustrated again are you?” he adds, smirking. A few more people have drifted back into the room; Williams’s presence is required next door, in the studio. So what’s the best and worst thing about being Pharrell Williams, I ask?

“The best thing,” he says, almost whispering, “is that you get to do what you wanna do.” He pauses, and wrings his hands together. “The worst thing....” He stops, leaving what feels like five minues of absolute silence. “The worst thing is that so many people don’t realize that that’s possible.”