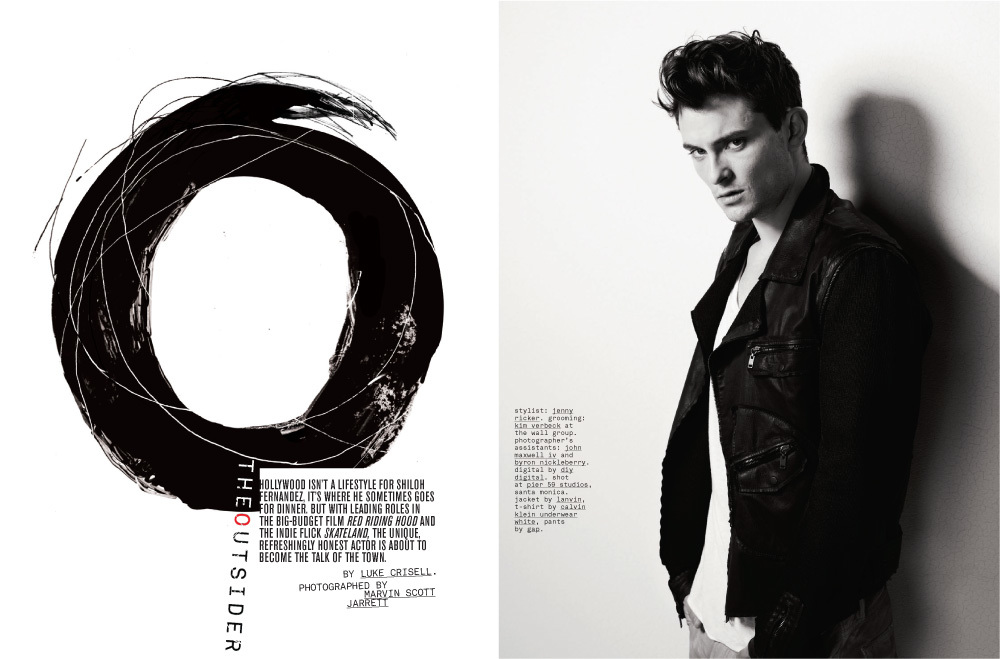

THE OUTSIDER

HOLLYWOOD ISN’T A LIFESTYLE FOR SHILOH FERNANDEZ, IT’S WHERE HE SOMETIMES GOES FOR DINNER. BUT WITH LEADING ROLES IN THE BIG-BUDGET FILM RED RIDING HOOD AND THE INDIE FLICK SKATELAND, THE UNIQUE, REFRESHINGLY HONEST ACTOR IS ABOUT TO BECOME THE TALK OF THE TOWN.

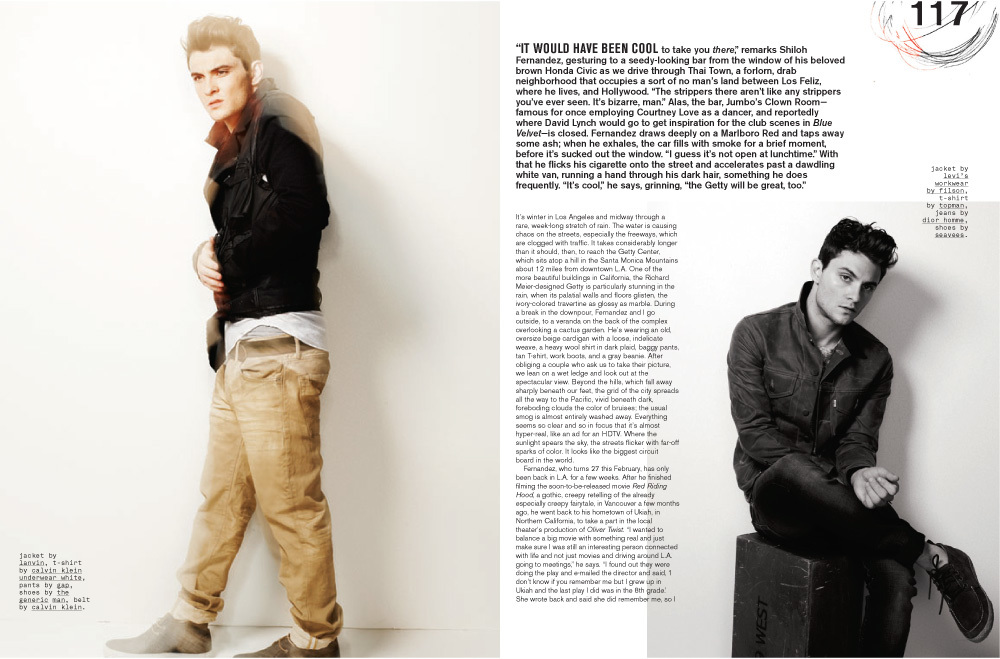

“IT WOULD HAVE BEEN COOL to take you there,” remarks Shiloh Fernandez, gesturing to a seedy-looking bar from the window of his beloved brown Honda Civic as we drive through Thai Town, a forlorn, drab neighborhood that occupies a sort of no man’s land between Los Feliz, where he lives, and Hollywood. “The strippers there aren’t like any strippers you’ve ever seen. It’s bizarre, man.” Alas, the bar, Jumbo’s Clown Room— famous for once employing Courtney Love as a dancer, and reportedly where David Lynch would go to get inspiration for the club scenes in Blue Velvet—is closed. Fernandez draws deeply on a Marlboro Red and taps away some ash; when he exhales, the car fills with smoke for a brief moment, before it’s sucked out the window. “I guess it’s not open at lunchtime.” With that he flicks his cigarette onto the street and accelerates past a dawdling white van, running a hand through his dark hair, something he does frequently. “It’s cool,” he says, grinning, “the Getty will be great, too.”

It’s winter in Los Angeles and midway through a rare, week-long stretch of rain. The water is causing chaos on the streets, especially the freeways, which are clogged with traffic. It takes considerably longer than it should, then, to reach the Getty Center, which sits atop a hill in the Santa Monica Mountains about 12 miles from downtown L.A. One of the more beautiful buildings in California, the Richard Meier-designed Getty is particularly stunning in the rain, when its palatial walls and floors glisten, the ivory-colored travertine as glossy as marble. During a break in the downpour, Fernandez and I go outside, to a veranda on the back of the complex overlooking a cactus garden. He’s wearing an old, oversize beige cardigan with a loose, indelicate weave, a heavy wool shirt in dark plaid, baggy pants, tan T-shirt, work boots, and a gray beanie. After obliging a couple who ask us to take their picture, we lean on a wet ledge and look out at the spectacular view. Beyond the hills, which fall away sharply beneath our feet, the grid of the city spreads all the way to the Pacific, vivid beneath dark, foreboding clouds the color of bruises; the usual smog is almost entirely washed away. Everything seems so clear and so in focus that it’s almost hyper-real, like an ad for an HDTV. Where the sunlight spears the sky, the streets flicker with far-off sparks of color. It looks like the biggest circuit board in the world.

Fernandez, who turns 27 this February, has only been back in L.A. for a few weeks. After he finished filming the soon-to-be-released movie Red Riding Hood, a gothic, creepy retelling of the already especially creepy fairytale, in Vancouver a few months ago, he went back to his hometown of Ukiah, in Northern California, to take a part in the local theater’s production of Oliver Twist. “I wanted to balance a big movie with something real and just make sure I was still an interesting person connected with life and not just movies and driving around L.A. going to meetings,” he says. “I found out they were doing the play and emailed the director and said, ‘I don’t know if you remember me but I grew up in Ukiah and the last play I did was in the 8th grade.’ She wrote back and said she did remember me, so I told her I’d love to be considered for the part of the Artful Dodger.” But that role was already taken, so Fernandez, who spent his time in Ukiah, a town that exports a considerable amount of wine, living in a yurt (“the smell of the fermenting grapes was beautiful”), ended up playing Bill Sikes. Dickens describes Sikes as a “stoutly-built fellow” with a “broad heavy countenance.” Fernandez, while not exactly diminutive, is certainly not physically imposing. “The director said that, but my idea was to play him as a young pimp who would slit people’s throats and was more of a psychopath than a big brute,” he says. “There’s one scene where Bill Sikes beats Nancy to control her, but instead of beating her, I said, ‘Why doesn’t he use his love to control her, rather than violence?’”

That he would re-imagine one of the more memorable villains in the history of literature is unsurprising if you know Fernandez, who approaches each and every role from his own unique perspective. Rather than audition for a director or casting agent, Fernandez would sooner have a conversation with them. This is precisely what happened when he went in to read for Skateland, the independent coming-of-age drama that premiered at Sundance in 2010 and which will be released—one imagines not coincidentally—a few weeks after Red Riding Hood this March. “A lot of young actors would have loved to play that part,” he says of Ritchie Wheeler, the manager of a soon-to-be-demolished roller disco in ’70s, small-town Texas. “And I went in—this is how it happens a lot of the time—and I got to talk to people and be honest about my feelings on the part and character. It’s always better to say, ‘This is why I like this, and this is how I connect to it.’ It’s a kid right out of high school, who doesn’t have a whole lot of direction—he’s just kind of hanging out with the same kids, staying in the job he had at high school. I feel like that could have been me if I hadn’t been pushed to go to college.”

Growing up in Ukiah (“It’s haiku spelled backwards, which is a cool fact”), Fernandez could have very easily ended up on a different path. The heart of what’s known as The Emerald Triangle, the town is one of the largest marijuana- growing centers in the world. “You drive down the street, and you see it in people’s front yards,” Fernandez says. “It was one of the first places to decriminalize weed. It seems like it would be a really peaceful, hippie way of life but it gets really violent and there’s trading in San Francisco and there’s other drugs....” We walk back to the museum, passing through glass doors, and head down a corridor to an exhibition called “The Secret Life of Drawings.” “Think about it: You see your older brother buying a Range Rover and big TVs—it seems like an easy way to go,” he says. “To sell weed and not get a real job.” Lots of the people Fernandez grew up with did just that: settled down, had kids. Not his high-school girlfriend though, who ended up going to college in Los Angeles. Fernandez went to his safety school, the University of Colorado at Boulder, and the two stayed together for some of his freshman year until, on his 19th birthday, she broke up with him. By that time, he had already dropped out of school and told his family and friends he was moving to L.A. to be with her (he promised his parents he would enroll in UCLA the following year). We pause in front of an 18th-century line drawing. It’s mid-week and the galleries are sparsely populated—the few people who are here move around quietly, unobtrusively. Fernandez ended up moving to L.A. as planned: “I thought maybe we could get back together,” he says, lowering his voice. “For me, that was my happiness.”

Upon arriving in L.A., Fernandez moved into an apartment in Venice Beach with the only other person he knew in the city, a friend of a friend of his dad’s. “It was shocking,” he recalls. “I had to work like five jobs just to pay rent.” Low on cash, he emailed American Apparel founder Dov Charney. When Fernandez was 15, Charney had approached him in a hotel lobby and asked him to model for the catalogue of his then-fledgling company. Fernandez modeled for him again when he was 17, and now, he figured, he could do it again. “So I was like, ‘Do you wanna take my picture?’ And he’s like, ‘Not at all, but I’m opening a store and you can work in the stock room.’ It was awful, the worst job ever.” Fernandez (who says he has “no desire to be a model”) also worked at a local farmer’s market selling honey, in a Chinese restaurant, and in a sandwich shop, “flipping ribs.” One day, he went on an audition at Warner Bros., a meeting set up by the woman who lived across the courtyard from his apartment—she was a casting director for Nickelodeon and, later, cast Fernandez on Drake & Josh, “very embarrassing”—and ended up scoring a part on the TV show Cold Case.

From there, Fernandez hired a manager and an agent and started auditioning regularly, getting some parts, losing out on others. “I was in a herd of kids and, basically, you have to believe in yourself and know that you have something to offer,” he says. “There’s a formula for television auditions, where you kind of breathe deeply”–he inhales dramatically–“and maybe flex your body, and I learned that pretty quickly. That’s why I don’t like doing TV, because it’s not challenging. You know what they want from you and what you’re supposed to do. You don’t get to be interesting or try different things or be strange. TV is just not stimulating to me.”

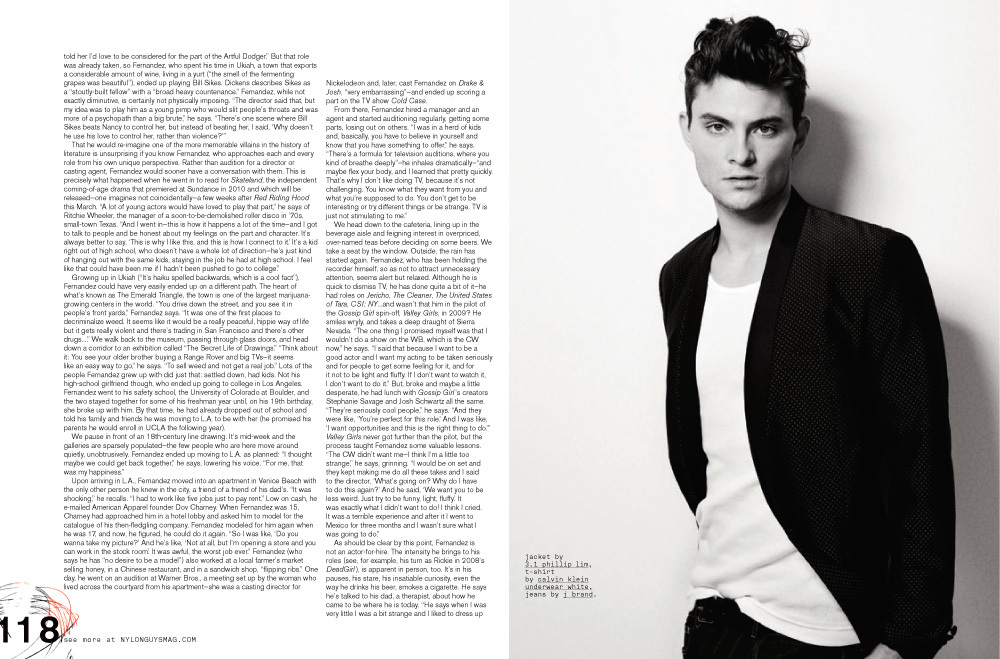

We head down to the cafeteria, lining up in the beverage aisle and feigning interest in overpriced, over-named teas before deciding on some beers. We take a seat by the window. Outside, the rain has started again. Fernandez, who has been holding the recorder himself, so as not to attract unnecessary attention, seems alert but relaxed. Although he is quick to dismiss TV, he has done quite a bit of it—he had roles on Jericho, The Cleaner, The United States of Tara, CSI: NY...and wasn’t that him in the pilot of the Gossip Girl spin-off, Valley Girls, in 2009? He smiles wryly, and takes a deep draught of Sierra Nevada. “The one thing I promised myself was that I wouldn’t do a show on the WB, which is the CW now,” he says. “I said that because I want to be a good actor and I want my acting to be taken seriously and for people to get some feeling for it, and for it not to be light and fluffy. If I don’t want to watch it, I don’t want to do it.” But, broke and maybe a little desperate, he had lunch with Gossip Girl ’s creators Stephanie Savage and Josh Schwartz all the same. “They’re seriously cool people,” he says. “And they were like, ‘You’re perfect for this role.’ And I was like, ‘I want opportunities and this is the right thing to do.’” Valley Girls never got further than the pilot, but the process taught Fernandez some valuable lessons. “The CW didn’t want me—I think I’m a little too strange,” he says, grinning. “I would be on set and they kept making me do all these takes and I said to the director, ‘What’s going on? Why do I have to do this again?’ And he said, ‘We want you to be less weird. Just try to be funny, light, fluffy.’ It was exactly what I didn’t want to do! I think I cried. It was a terrible experience and after it I went to Mexico for three months and I wasn’t sure what I was going to do.”

As should be clear by this point, Fernandez is not an actor-for-hire. The intensity he brings to his roles (see, for example, his turn as Rickie in 2008’s DeadGirl ), is apparent in person, too. It’s in his pauses, his stare, his insatiable curiosity, even the way he drinks his beer, smokes a cigarette. He says he’s talked to his dad, a therapist, about how he came to be where he is today. “He says when I was very little I was a bit strange and I liked to dress up and stuff,” he says. “But I was never sure what I was going to do. I feel like when I have a monumental shift in my life, or a newfound joy or love, I make a note of that feeling and sit in it, whether it’s good or bad.” That he’s had an interesting life has, he says, informed his work. “I thought maybe I have something to offer in terms of being an actor because I remember feelings and I know how to share those emotions with people.”

To date, Fernandez has been sharing his emotions with a fairly select audience. That will change in March when he appears as a woodcutter named Peter opposite Amanda Seyfried in Warner Bros.’ Red Riding Hood, a big-budget, special-effects-laden thriller directed by Catherine Hardwicke, whose résumé includes Thirteen, Lords of Dogtown, and Twilight, of which Fernandez was almost the star. It was Fernandez’s girlfriend at the time, the actress Juno Temple, who suggested to him he would be perfect for the part of Edward Cullen (she was reading the book). After a series of auditions, with a deal negotiated and a contract signed, the part was practically his. Then he screen-tested with Kristen Stewart, who had already been cast as Bella Swan. “I wanted to talk about the relationship and the part, and she hadn’t read the book,” he says, the frustration still evident in his voice. “She was sitting on the kitchen counter biting her nails and kicking her feet and I’m like, ‘What’s going on? Do you know how to speak? Can we communicate about this?’ So I ended up ignoring her and talking to Catherine. What I didn’t realize of course was that she has a big say because she’s the lead girl and you have to have chemistry.”

Hardwicke, who seems to have taken Fernandez under her wing in much the same way she did for Nikki Reed in Thirteen, remembers when he first walked in to audition, in her garage. “I thought it was Joaquin Phoenix with a fake name fucking with me,” she says. “I know [Phoenix] a little and the way Shiloh looked, I really thought it was him. Eventually I realized it wasn’t, but I knew this guy was unique. There was something really interesting about him, something fascinating. I had high hopes for him, but then when Kristen and Rob met.... You know, it was legendary.” She laughs. “It was game over right there.”

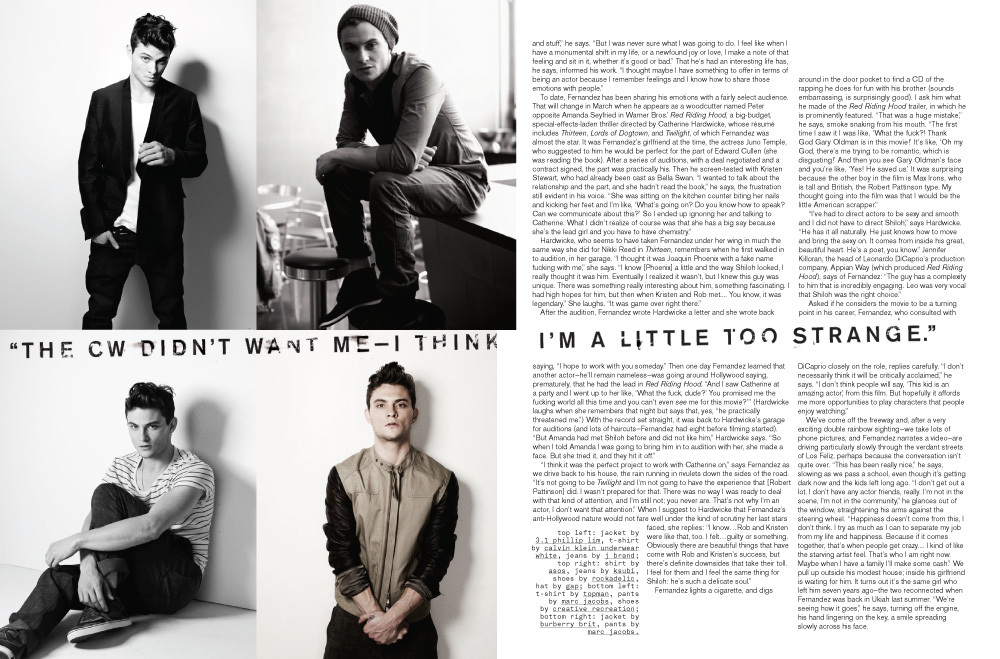

After the audition, Fernandez wrote Hardwicke a letter and she wrote back saying, “I hope to work with you someday.” Then one day Fernandez learned that another actor—he’ll remain nameless—was going around Hollywood saying, prematurely, that he had the lead in Red Riding Hood. “And I saw Catherine at a party and I went up to her like, ‘What the fuck, dude?’ You promised me the fucking world all this time and you can’t even see me for this movie?’” (Hardwicke laughs when she remembers that night but says that, yes, “he practically threatened me.”) With the record set straight, it was back to Hardwicke’s garage for auditions (and lots of haircuts—Fernandez had eight before filming started). “But Amanda had met Shiloh before and did not like him,” Hardwicke says. “So when I told Amanda I was going to bring him in to audition with her, she made a face. But she tried it, and they hit it off.”

“I think it was the perfect project to work with Catherine on,” says Fernandez as we drive back to his house, the rain running in rivulets down the sides of the road. “It’s not going to be Twilight and I’m not going to have the experience that [Robert Pattinson] did. I wasn’t prepared for that. There was no way I was ready to deal with that kind of attention, and I’m still not; you never are. That’s not why I’m an actor, I don’t want that attention.” When I suggest to Hardwicke that Fernandez’s anti-Hollywood nature would not fare well under the kind of scrutiny her last stars faced, she replies: “I know…Rob and Kristen were like that, too. I felt…guilty or something. Obviously there are beautiful things that have come with Rob and Kristen’s success, but there’s definite downsides that take their toll. I feel for them and I feel the same thing for Shiloh: he’s such a delicate soul.”

Fernandez lights a cigarette, and digs around in the door pocket to find a CD of the rapping he does for fun with his brother (sounds embarrassing, is surprisingly good). I ask him what he made of the Red Riding Hood trailer, in which he is prominently featured. “That was a huge mistake,” he says, smoke snaking from his mouth. “The first time I saw it I was like, ‘What the fuck?! Thank God Gary Oldman is in this movie!’ It’s like, ‘Oh my God, there’s me trying to be romantic, which is disgusting!’ And then you see Gary Oldman’s face and you’re like, ‘Yes! He saved us.’ It was surprising because the other boy in the film is Max Irons, who is tall and British, the Robert Pattinson type. My thought going into the film was that I would be the little American scrapper.”

“I’ve had to direct actors to be sexy and smooth and I did not have to direct Shiloh,” says Hardwicke.

“He has it all naturally. He just knows how to move and bring the sexy on. It comes from inside his great, beautiful heart. He’s a poet, you know.” Jennifer Killoran, the head of Leonardo DiCaprio’s production company, Appian Way (which produced Red Riding Hood), says of Fernandez: “The guy has a complexity to him that is incredibly engaging. Leo was very vocal that Shiloh was the right choice.”

Asked if he considers the movie to be a turning point in his career, Fernandez, who consulted with DiCaprio closely on the role, replies carefully. “I don’t necessarily think it will be critically acclaimed,” he says. “I don’t think people will say, ‘This kid is an amazing actor,’ from this film. But hopefully it affords me more opportunities to play characters that people enjoy watching.”

We’ve come off the freeway and, after a very exciting double rainbow sighting—we take lots of phone pictures, and Fernandez narrates a video—are driving particularly slowly through the verdant streets of Los Feliz, perhaps because the conversation isn’t quite over. “This has been really nice,” he says, slowing as we pass a school, even though it’s getting dark now and the kids left long ago. “I don’t get out a lot. I don’t have any actor friends, really. I’m not in the scene, I’m not in the community,” he glances out of the window, straightening his arms against the steering wheel. “Happiness doesn’t come from this, I don’t think. I try as much as I can to separate my job from my life and happiness. Because if it comes together, that’s when people get crazy.... I kind of like the starving artist feel. That’s who I am right now. Maybe when I have a family I’ll make some cash.” We pull up outside his modest house; inside his girlfriend is waiting for him. It turns out it’s the same girl who left him seven years ago–the two reconnected when Fernandez was back in Ukiah last summer. “We’re seeing how it goes,” he says, turning off the engine, his hand lingering on the key, a smile spreading slowly across his face.