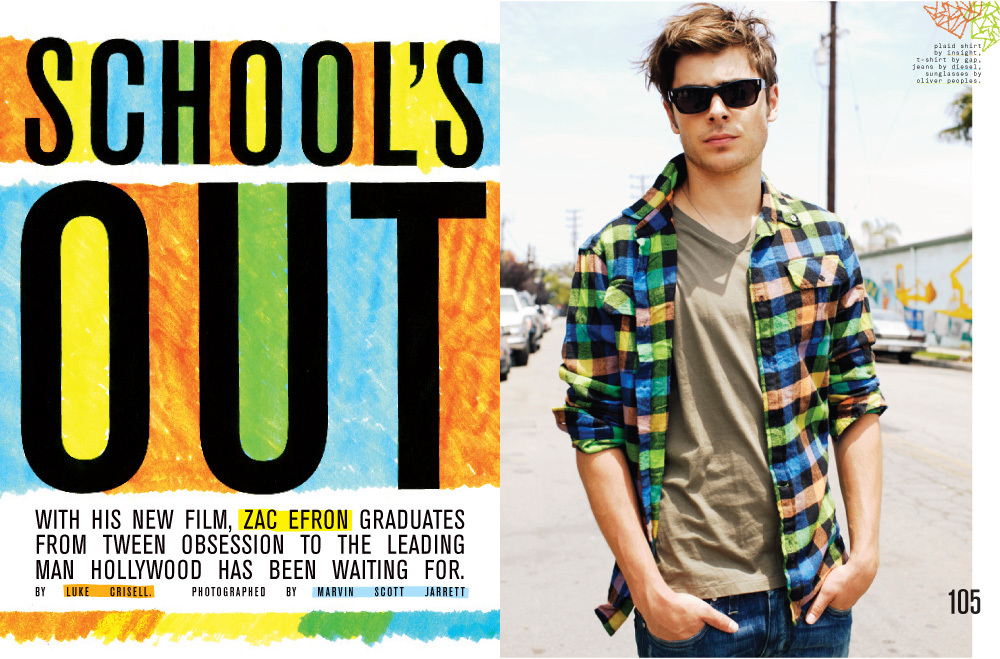

SCHOOL’S OUT

WITH HIS NEW FILM, ZAC EFRON GRADUATES FROM TWEEN OBSESSION TO THE LEADING MAN HOLLYWOOD HAS BEEN WAITING FOR.

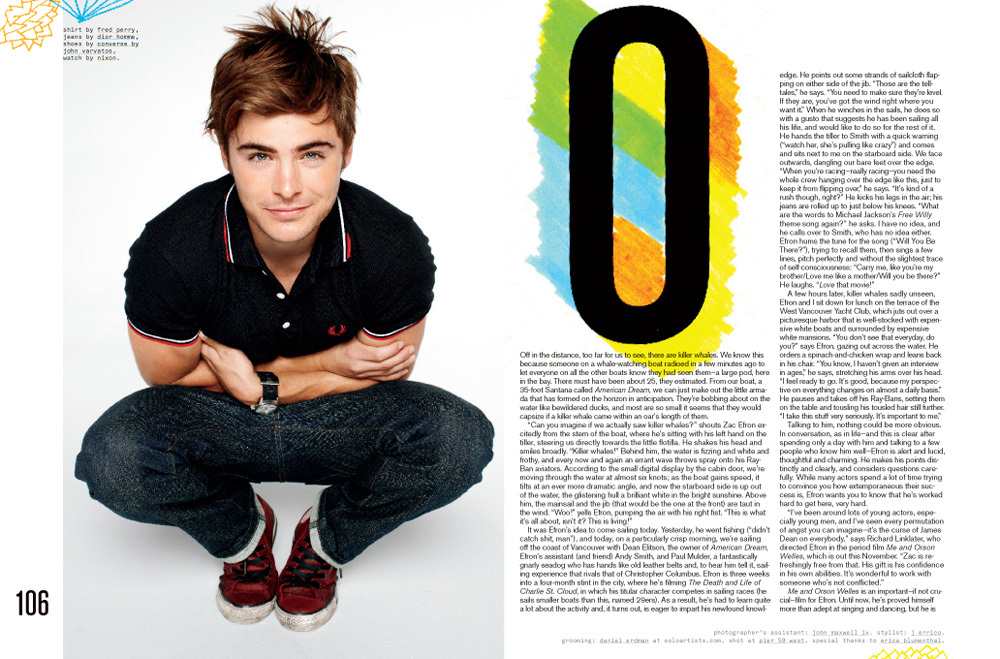

OFF IN THE distance, too far for us to see, there are killer whales. We know this because someone on a whale-watching boat radioed in a few minutes ago to let everyone on all the other boats know they had seen them—a large pod, here in the bay. There must have been about 25, they estimated. From our boat, a 35-foot Santana called American Dream, we can just make out the little armada that has formed on the horizon in anticipation. They’re bobbing about on the water like bewildered ducks, and most are so small it seems that they would capsize if a killer whale came within an oar’s length of them.

“Can you imagine if we actually saw killer whales?” shouts Zac Efron excitedly from the stern of the boat, where he’s sitting with his left hand on the tiller, steering us directly towards the little flotilla. He shakes his head and smiles broadly. “Killer whales!” Behind him, the water is fizzing and white and frothy, and every now and again an errant wave throws spray onto his Ray-Ban aviators. According to the small digital display by the cabin door, we’re moving through the water at almost six knots; as the boat gains speed, it tilts at an ever more dramatic angle, and now the starboard side is up out of the water, the glistening hull a brilliant white in the bright sunshine. Above him, the mainsail and the jib (that would be the one at the front) are taut in the wind. “Woo!” yells Efron, pumping the air with his right fist. “This is what it’s all about, isn’t it? This is living!”

It was Efron’s idea to come sailing today. Yesterday, he went fishing (“didn’t catch shit, man”), and today, on a particularly crisp morning, we’re sailing off the coast of Vancouver with Dean Elitson, the owner of American Dream, Efron’s assistant (and friend) Andy Smith, and Paul Mulder, a fantastically gnarly seadog who has hands like old leather belts and, to hear him tell it, sailing experience that rivals that of Christopher Columbus. Efron is three weeks into a four-month stint in the city, where he’s filming The Death and Life of Charlie St. Cloud, in which his titular character competes in sailing races (he sails smaller boats than this, named 29ers). As a result, he’s had to learn quite a lot about the activity and, it turns out, is eager to impart his newfound knowledge. He points out some strands of sailcloth flapping on either side of the jib. “Those are the tell-tales,” he says. “You need to make sure they’re level. If they are, you’ve got the wind right where you want it.” When he winches in the sails, he does so with a gusto that suggests he has been sailing all his life, and would like to do so for the rest of it. He hands the tiller to Smith with a quick warning (“watch her, she’s pulling like crazy”) and comes and sits next to me on the starboard side. We face outwards, dangling our bare feet over the edge. “When you’re racing—really racing—you need the whole crew hanging over the edge like this, just to keep it from flipping over,” he says. “It’s kind of a rush though, right?” He kicks his legs in the air; his jeans are rolled up to just below his knees. “What are the words to Michael Jackson’s Free Willy theme song again?” he asks. I have no idea, and he calls over to Smith, who has no idea either. Efron hums the tune for the song (“Will You Be There?”), trying to recall them, then sings a few lines, pitch perfectly and without the slightest trace of self-consciousness: “Carry me, like you’re my brother/Love me like a mother/Will you be there?” He laughs. “Love that movie!”

A few hours later, killer whales sadly unseen, Efron and I sit down for lunch on the terrace of the West Vancouver Yacht Club, which juts out over a picturesque harbor that is well-stocked with expensive white boats and surrounded by expensive white mansions. “You don’t see that everyday, do you?” says Efron, gazing out across the water. He orders a spinach-and-chicken wrap and leans back in his chair. “You know, I haven’t given an interview in ages,” he says, stretching his arms over his head. “I feel ready to go. It’s good, because my perspective on everything changes on almost a daily basis.” He pauses and takes off his Ray-Bans, setting them on the table and tousling his tousled hair still further. “I take this stuff very seriously. It’s important to me.”

Talking to him, nothing could be more obvious. In conversation, as in life—and this is clear after spending only a day with him and talking to a few people who know him well—Efron is alert and lucid, thoughtful and charming. He makes his points distinctly and clearly, and considers questions carefully. While many actors spend a lot of time trying to convince you how extemporaneous their success is, Efron wants you to know that he’s worked hard to get here, very hard.

“I’ve been around lots of young actors, especially young men, and I’ve seen every permutation of angst you can imagine—it’s the curse of James Dean on everybody,” says Richard Linklater, who directed Efron in the period film Me and Orson Welles, which is out this November. “Zac is refreshingly free from that. His gift is his confidence in his own abilities. It’s wonderful to work with someone who’s not conflicted.”

Me and Orson Welles is an important—if not crucial—film for Efron. Until now, he’s proved himself more than adept at singing and dancing, but he is not exactly known for his acting ability. Which isn’t to say he can’t act: He was, in fact, great in 17 Again, as the 17-year-old Michael O’Donnell (who’s actually in his mid thirties; the older version is played by Matthew Perry), zipping around in his Audi R8 and causing something of a stir among his high school’s female population. But while the entirely enjoyable film—which was directed by Burr Steers (Igby Goes Down), who also directs him in Charlie St. Cloud—certainly showed that Efron could do more than sing and dance, it was not exactly a hit among those of us older than 13. Plus, the opening sequence finds him, once again, on a basketball court.

As it happens, he does sing a bit in Orson Welles, too (and play the lute a little, if you must know), but it is nevertheless the first film Efron has made that appeals directly to a more adult audience (it is also unlikely to alienate his established fanbase—but it’s debatable whether anything could at this point). The film tells the story of a week in the young director’s life in New York City in 1937, as he prepares to stage a production of Julius Ceasar (the Roman senators and citizenry wear fascist uniforms) at the infamous Mercury Theatre. Efron plays aspiring actor Richard, who is thrust into the production after being spotted singing on the street by Welles and has to quickly learn not just the ropes of a major theatrical production, but the myriad idiosyncrasies of one of the most idiosyncratic figures in the history of entertainment. The interior of the Mercury Theatre was recreated for the film on the Isle of Man, and Linklater recruited the kind of actors—Eddie Marsan, Ben Chaplin, brilliant newcomer Christian McKay—who give the impression that they have been treading the boards since the time they could walk. What on earth, they might have been forgiven for wondering, was That Pretty Disney Kid From High School Musical doing there?

“I think it did create a certain dissonance for some people, but I was never conflicted about it,” says Linklater. “Zac had every right to be a little bit intimidated: These are top-notch actors—they all have Olivier Awards. But he just jumped right in and worked his ass off. The guy is a natural-born performer and doesn’t ever question his own talent. It was amazing to see. He’s like an athlete who’s in the major leagues aged 21 and thinks he belongs there, ’cause he does. You can’t fake that kind of confidence.”

“I had to do this movie,” says Efron. “I would love to say that I sat down and really thought what would come next and whether there was some master plan to this. But Rick asked me if I wanted to do the movie, and I said, ‘Hell, yeah.’ And it’s the first time I’ve ever watched a movie [that I’m in] and at the end I’m like, ‘OK! I didn’t check my watch once!’ During the 17 Again premiere I was squinting the whole movie.... It was ridiculous.” “I remember when I met him, Zac asked me, ‘Have you seen High School Musical?’” says Linklater. “And I said I hadn’t, and he smiled and said, ‘Well that’s good, or we might not be sitting here.’ But I don’t think that’s true. I learned a long time ago that you can’t judge young artists, particularly actors, on something you saw. You’ve got to sit down with them and find out how they are. And I knew right off the bat, OK, this guy is the real deal. This guy is going to have a long career.”

ZAC EFRON WAS BORN in San Luis Obispo, California, and had what he calls “a pretty normal, middle-class upbringing,” in nearby Arroyo Grande. Early on, he had an affinity for music. “It all started with music,” he says. “I was constantly singing. I would hear things on the radio and just be able to spit them out instantly, with perfect memorization and tone. It wasn’t like I took pride in it; there was no effort. My parents were like, ‘Shut up. Please stop singing. It’s annoying.’” He laughs. Nevertheless, Efron’s parents recognized their son’s talents and started taking him to auditions in Los Angeles. “I didn’t tell anyone,” he says. “I had to come up with excuses at school. Everyone started to wonder what the hell was going on.” His parents, he says, supported him while carefully managing his career expectations. “I always expected the worse,” he says. “I knew it was doomed to failure before it even began.” He didn’t book much, but the few small parts he did get electrified him. “I felt like I was the most awake I could be,” he says. The other kids at school eventually found out about their peer’s forays into showbiz (he was on TV, after all) and would tease him ruthlessly. “Everyone would have their laughs and poke fun and stuff, but secretly, I was 10 steps ahead,” he says, a twinkle in his eye. “I was making more money than I ever dreamed of. It was real. It wasn’t a dream.” He takes a gulp of water and looks out across the bay. “As you can imagine, it was pretty distracting once it all started to happen.” There came a day when Efron had to choose whether to finish filming Hairspray or go to college (he’d been accepted to USC and UCLA). Of course, he chose to finish filming. “I still haven’t lived it down,” he says. “I’m gonna have to go sooner or later.” The waiter delivers our food, and Efron pops some chips into his mouth. “But college will always be there. This is a moment I’m gaining.”

Efron’s break—the thing that has made him one of the most famous people on the planet and ensured his image is on lunchboxes and almost every other accoutrement imaginable across the world— was, of course, High School Musical. The franchise is one of the most successful, and most valuable, in the history of cable television. Although he was officially part of an ensemble cast with six main players, Efron—who plays captain of the basketball team, Troy Bolton—has emerged as the male face of the franchise (the female one is his love interest in the movie, and girlfriend in real life, Vanessa Hudgens). There are three films in total, and I tell him that last night I watched them all, back-to-back. “Oh God, you must be hungover!” Efron says, laughing. The thing is, they’re actually not that bad at all. They have their place, and that is front and center in the most wholesome possible vision of the American Dream (Efron and Hudgens’s characters do not actually kiss in any of the films). “Put your mind to it,” they’re saying, “and you can achieve anything.”

“That was how I felt, and I wanted to share that with the world: You don’t have to live inside the box,” Efron says. “Growing up and hearing that and believing that is the reason that I got here. That’s what High School Musical is about. And man, you should see the faces on the kids. It’s priceless, and I don’t look down on, or think badly about, those films. I have no regrets at all. I’m extremely proud of those movies, and will be forever.”

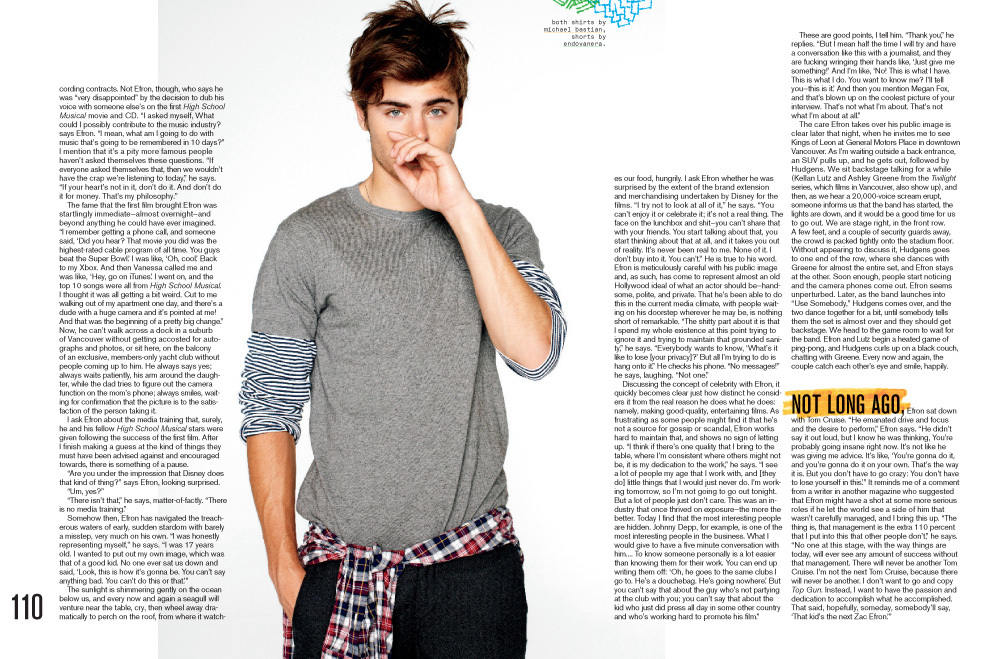

Following the success of High School Musical 1, 2, and 3, many of the stars signed valuable recording contracts. Not Efron, though, who says he was “very disappointed” by the decision to dub his voice with someone else’s on the first High School Musical movie and CD. “I asked myself, What could I possibly contribute to the music industry? says Efron. “I mean, what am I going to do with music that’s going to be remembered in 10 days?” I mention that it’s a pity more famous people haven’t asked themselves these questions. “If everyone asked themselves that, then we wouldn’t have the crap we’re listening to today,” he says. “If your heart’s not in it, don’t do it. And don’t do it for money. That’s my philosophy.”

The fame that the first film brought Efron was startlingly immediate—almost overnight—and beyond anything he could have ever imagined. “I remember getting a phone call, and someone said, ‘Did you hear? That movie you did was the highest-rated cable program of all time. You guys beat the Super Bowl.’ I was like, ‘Oh, cool.’ Back to my Xbox. And then Vanessa called me and was like, ‘Hey, go on iTunes.’ I went on, and the top 10 songs were all from High School Musical. I thought it was all getting a bit weird. Cut to me walking out of my apartment one day, and there’s a dude with a huge camera and it’s pointed at me! And that was the beginning of a pretty big change.” Now, he can’t walk across a dock in a suburb of Vancouver without getting accosted for autographs and photos, or sit here, on the balcony of an exclusive, members-only yacht club without people coming up to him. He always says yes; always waits patiently, his arm around the daughter, while the dad tries to figure out the camera function on the mom’s phone; always smiles, waiting for confirmation that the picture is to the satisfaction of the person taking it.

I ask Efron about the media training that, surely, he and his fellow High School Musical stars were given following the success of the first film. After I finish making a guess at the kind of things they must have been advised against and encouraged towards, there is something of a pause.

“Are you under the impression that Disney does that kind of thing?” says Efron, looking surprised.

“Um, yes?”

“There isn’t that,” he says, matter-of-factly. “There is no media training.”

Somehow then, Efron has navigated the treacherous waters of early, sudden stardom with barely a misstep, very much on his own. “I was honestly representing myself,” he says. “I was 17 years old. I wanted to put out my own image, which was that of a good kid. No one ever sat us down and said, ‘Look, this is how it’s gonna be. You can’t say anything bad. You can’t do this or that.’”

The sunlight is shimmering gently on the ocean below us, and every now and again a seagull will venture near the table, cry, then wheel away dramatically to perch on the roof, from where it watches our food, hungrily. I ask Efron whether he was surprised by the extent of the brand extension and merchandising undertaken by Disney for the films. “I try not to look at all of it,” he says. “You can’t enjoy it or celebrate it; it’s not a real thing. The face on the lunchbox and shit—you can’t share that with your friends. You start talking about that, you start thinking about that at all, and it takes you out of reality. It’s never been real to me. None of it. I don’t buy into it. You can’t.” He is true to his word. Efron is meticulously careful with his public image and, as such, has come to represent almost an old Hollywood ideal of what an actor should be—handsome, polite, and private. That he’s been able to do this in the current media climate, with people waiting on his doorstep wherever he may be, is nothing short of remarkable. “The shitty part about it is that I spend my whole existence at this point trying to ignore it and trying to maintain that grounded sanity,” he says. “Everybody wants to know, ‘What’s it like to lose [your privacy]?’ But all I’m trying to do is hang onto it.” He checks his phone. “No messages!” he says, laughing. “Not one.”

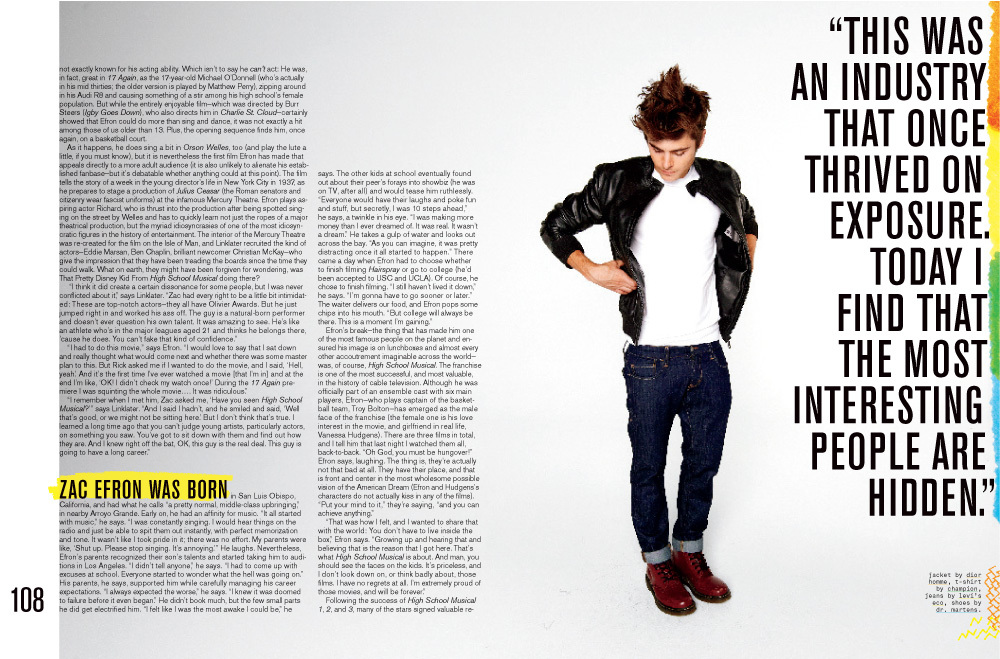

Discussing the concept of celebrity with Efron, it quickly becomes clear just how distinct he considers it from the real reason he does what he does: namely, making good-quality, entertaining films. As frustrating as some people might find it that he’s not a source for gossip or scandal, Efron works hard to maintain that, and shows no sign of letting up. “I think if there’s one quality that I bring to the table, where I’m consistent where others might not be, it is my dedication to the work,” he says. “I see a lot of people my age that I work with, and [they do] little things that I would just never do. I’m work- ing tomorrow, so I’m not going to go out tonight. But a lot of people just don’t care. This was an industry that once thrived on exposure—the more the better. Today I find that the most interesting people are hidden. Johnny Depp, for example, is one of the most interesting people in the business. What I would give to have a five minute conversation with him.... To know someone personally is a lot easier than knowing them for their work. You can end up writing them off: ‘Oh, he goes to the same clubs I go to. He’s a douchebag. He’s going nowhere.’ But you can’t say that about the guy who’s not partying at the club with you; you can’t say that about the kid who just did press all day in some other country and who’s working hard to promote his film.”

These are good points, I tell him. “Thank you,” he replies. “But I mean half the time I will try and have a conversation like this with a journalist, and they are fucking wringing their hands like, ‘Just give me something!’ And I’m like, ‘No! This is what I have. This is what I do. You want to know me? I’ll tell you—this is it.’ And then you mention Megan Fox, and that’s blown up on the coolest picture of your interview. That’s not what I’m about. That’s not what I’m about at all.” The care Efron takes over his public image is clear later that night, when he invites me to see Kings of Leon at General Motors Place in downtown Vancouver. As I’m waiting outside a back entrance, an SUV pulls up, and he gets out, followed by Hudgens. We sit backstage talking for a while (Kellan Lutz and Ashley Greene from the Twilight series, which films in Vancouver, also show up), and then, as we hear a 20,000-voice scream erupt, someone informs us that the band has started, the lights are down, and it would be a good time for us to go out. We are stage right, in the front row. A few feet, and a couple of security guards away, the crowd is packed tightly onto the stadium floor. Without appearing to discuss it, Hudgens goes to one end of the row, where she dances with Greene for almost the entire set, and Efron stays at the other. Soon enough, people start noticing and the camera phones come out. Efron seems unperturbed. Later, as the band launches into “Use Somebody,” Hudgens comes over, and the two dance together for a bit, until somebody tells them the set is almost over and they should get backstage. We head to the game room to wait for the band. Efron and Lutz begin a heated game of ping-pong, and Hudgens curls up on a black couch, chatting with Greene. Every now and again, the couple catch each other’s eye and smile, happily.

NOT LONG AGO, Efron sat down with Tom Cruise. “He emanated drive and focus and the desire to perform,” Efron says. “He didn’t say it out loud, but I know he was thinking, You’re probably going insane right now. It’s not like he was giving me advice. It’s like, ‘You’re gonna do it, and you’re gonna do it on your own. That’s the way it is. But you don’t have to go crazy: You don’t have to lose yourself in this.’” It reminds me of a comment from a writer in another magazine who suggested that Efron might have a shot at some more serious roles if he let the world see a side of him that wasn’t carefully managed, and I bring this up. “The thing is, that management is the extra 110 percent that I put into this that other people don’t,” he says. “No one at this stage, with the way things are today, will ever see any amount of success without that management. There will never be another Tom Cruise. I’m not the next Tom Cruise, because there will never be another. I don’t want to go and copy Top Gun. Instead, I want to have the passion and dedication to accomplish what he accomplished. That said, hopefully, someday, somebody’ll say, ‘That kid’s the next Zac Efron.’”